Anthony Cudahy’s recent paintings incorporate the apocalyptic zeitgeist of ongoing pandemics with his unceasing interest in photography. His crepuscular scenes are dispersed with saturated, glowing light, depicting near and far pasts. Cudahy often sources archival photographs as a catalyst for his works, and in doing so, gently motions toward alternate histories and imagined futures.

We spoke to the Brooklyn-based artist about emotive, purgatorial spaces, Pompeii and the Everard Bathhouse, and his reimagining of hagiographic icons. Cudahy’s work is currently on view at Deli Gallery in a collaborative show.

We spoke to the Brooklyn-based artist about emotive, purgatorial spaces, Pompeii and the Everard Bathhouse, and his reimagining of hagiographic icons. Cudahy’s work is currently on view at Deli Gallery in a collaborative show.

![]()

Under and behind (Narcissus on the table, mutant flower outside), 2020,

oil and acrylic on canvas, 70 x 96 inches

Under and behind (Narcissus on the table, mutant flower outside), 2020,

oil and acrylic on canvas, 70 x 96 inches

I like to start off with an icebreaker, which is, do you have a rose and a thorn for the past week?

I was thinking about this for your interview series. I would say that the rose for my week is that my COVID-delayed thesis show is going to open, and I was able to finally install it over the weekend. But then it's also the thorn, because starting Thursday, we have to be there every day for 10 days. I'm a little bit stressed about interacting with visitors and people, because I've pretty much only been home and in the studio this past year.

So you have your thesis show and you have a solo exhibition at 1969 right now. Can you tell us about what you're getting at with these bodies of work?

The show at 1969 is titled Burn Across the Breeze. The paintings that I made for it are from the middle of the summer when I moved into a studio near my house. Before that, from March on, Hunter closed down the studios and I was making works on paper and smaller paintings at home. I had a lot of pent up energy before I moved into my husband's studio and started to make the work for that show, which is pretty much from the second half of the year. It’s definitely processing what the world became, but a lot of the themes in the paintings were already in my work.

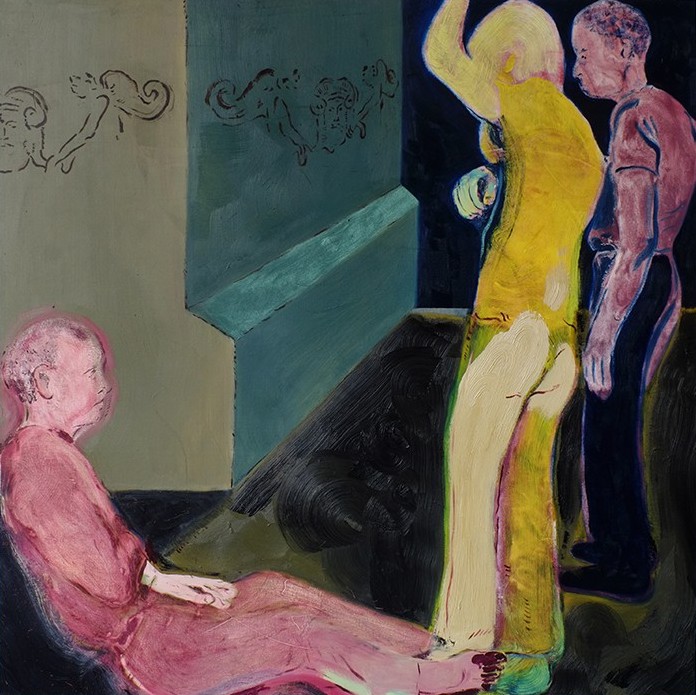

The theme of waiting, or being in purgatorial space, is something that's been present in my work for a long time, but it’s developed a very specific meaning this past year. I used to do more group paintings, which I still do, but I noticed that most of the pieces for this show featured solitary figures or two fingers entwined, so I made a foil painting which is the big group painting [Crowd (day and night), 2020] that's in the show.

A lot of the symbolism in the show is set up either through the composition, the light, or the color in the pieces, where these figures are stuck between looking over into new zones. There's figures that are at a fence, or there's figures that are behind or at the edge of a wall. They work to demarcate a different feeling or an emotive space. While I was making the paintings, I started to repeat a lot of symbols, like the lion that's eating its own tail, which I feel like relates to the ropes as well. There’s a lot of knotting and trying to untie a very complicated situation. There's one painting in the back of the show [Painful Unknotting, 2020], with a woman hard at work on a knotted rope, but then there's this knife near her, so maybe it's another way out of the situation.

The theme of waiting, or being in purgatorial space, is something that's been present in my work for a long time, but it’s developed a very specific meaning this past year. I used to do more group paintings, which I still do, but I noticed that most of the pieces for this show featured solitary figures or two fingers entwined, so I made a foil painting which is the big group painting [Crowd (day and night), 2020] that's in the show.

A lot of the symbolism in the show is set up either through the composition, the light, or the color in the pieces, where these figures are stuck between looking over into new zones. There's figures that are at a fence, or there's figures that are behind or at the edge of a wall. They work to demarcate a different feeling or an emotive space. While I was making the paintings, I started to repeat a lot of symbols, like the lion that's eating its own tail, which I feel like relates to the ropes as well. There’s a lot of knotting and trying to untie a very complicated situation. There's one painting in the back of the show [Painful Unknotting, 2020], with a woman hard at work on a knotted rope, but then there's this knife near her, so maybe it's another way out of the situation.

![]()

Crowd (day and night), 2020

oil on canvas, 72 x 49 inches

Does this have to do with the Gordian knot and the idea of attempting to do something that's really difficult or impossible, but then having the knife there as the path to untying it or completing an otherwise impossible task?

I was definitely thinking about that when I situated that work towards the back of the show [Painful Uknotting, 2020], as an ending task. That gave the potential for there to be another solution outside of whatever logic we're currently using. In that case, the knife is more of a violent or destructive reading. And that painting relates to another [CUT THE WORLD, 2020], right at the start of the show, that has a figure, who I think of as more of a protective figure, holding a blade up and making eye contact with the viewer.

But I don’t want any of the symbols or narratives that I set up to be fixed or have one meaning: I want an imaginative zone. There's obviously a group of symbols that I like. When I'm setting up a show, I try to have them recurring and playing off of other paintings in the show. Sometimes it’s a romantic gesture, where the knot is a way to display two fingers entwined.

But I don’t want any of the symbols or narratives that I set up to be fixed or have one meaning: I want an imaginative zone. There's obviously a group of symbols that I like. When I'm setting up a show, I try to have them recurring and playing off of other paintings in the show. Sometimes it’s a romantic gesture, where the knot is a way to display two fingers entwined.

![]()

Painful Unknotting, 2020

oil and acrylic on canvas, 36 x 48 inches

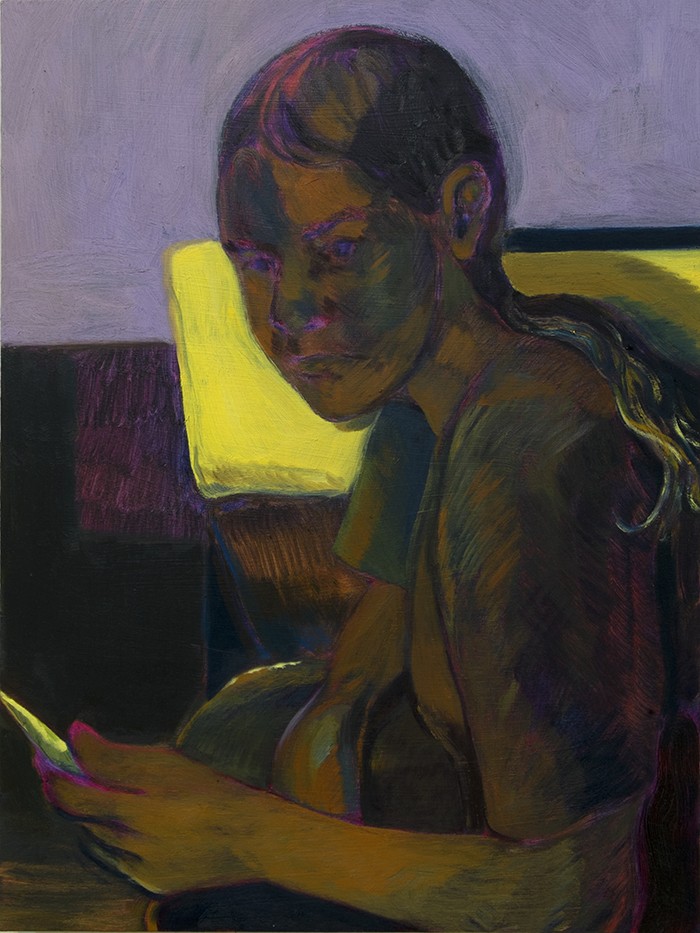

Flowers are also a recurring motif throughout your works. Can you talk about your attachment to flowers? I’m thinking specifically of an older work, “three” (2019), where two figures at a bar are looking at a flower that seems to be the source of the light on their faces.

There’s a painting in this show which I feel like really relates to the one that you're talking about [Under and behind (Narcissus on the table, mutant flower outside), 2020]. With both of them, I was thinking of the flower as an alien or supernatural force in the painting. In three the flowers are the source of the light the figures are entranced by. In Under and behind there's this mirrored mutant flower in the outside section of the painting. Another figure is a take on the Narcissus figure, and that specific flower is on the table, combining that history and narrative lineage. I also formally love a lot of tapestries and in Burn Across the Breeze, in particular, I was working a lot with this. There’s this French apocalypse tapestry which a lot of the floral elements came from, but I just love the mastery of simplicity and the economy of those forms.

I find it interesting that you were working with these themes before they became more specifically applicable to our society, (ie. a global pandemic). You have a painting in the “Night Paintings” group, called “Domestic Painting” featuring “The Triumph of Death”–are you referencing violence in an intimate space or relating a kind of tenderness to pain?

I definitely don't want to close out that reading, because I definitely think a lot of my paintings are about that. But in 2018, where my head was at with that painting in particular, was earlier in this queer figurative moment. A lot of the work that I do fits into that as well, and though it wasn't so much a critique painting, I kind of wanted to do the same thing that Breughel’s Triumphs of Death (c. 1562) painting was doing. Within that painting, there's the two lovers who are so entwined with each other that they don't notice that the apocalypse is happening, and there's even a weird skeleton figure that's playing music, almost like romantic music, for them. I was questioning what it means to focus on interpersonal relationships while the world is burning. I also don't want to critique, because I think a great part of painting is its potential for the artist to portray something that they love, or that they are attracted to, or are drawn to. That is a very intrinsic thing that obviously can be problematic or it can be generative–and sometimes both.

![]()

Domestic Painting (with excerpt from Triumph of Death),

2018, oil on canvas, 48 x 60 inches

These objects (flowers, etc.) are sometimes art historical references, from archival photos, or even at times neither of those things. But they all end up within the same picture plane or in a set of works. Do you find that these objects are then conceptually equalized?

The way that I've always thought about painting, and this is true of the painters that I am drawn to the most, is that it’s like a dialogue, a call and response. Painting is a very inwardly looking medium, and artists have always responded to older paintings. At the present moment, I'm not someone who's super interested in doing something new. I like the tradition of painting, and I like that it's a reflective medium in a sentimental way. I kind of feel like a collector of imagery. I’m able to use what I’ve collected and make something in response. It’s a back and forth, in a beautiful way, where you influence past painting or artwork as much as it has influenced you; and you change its context as much as it changes yours. I don't know if that answered your question, but that's kind of how I see it!

I'm not interested in using the past as a genre exercise. A lot of times, people quote periods of time, and the message is that it's being quoted or referenced. I think the equalizing that you're talking about is a way to set up a scenario where these disparate things exist in the same world. It's not necessarily the genre that drew me to whichever symbol I picked up.

I'm not interested in using the past as a genre exercise. A lot of times, people quote periods of time, and the message is that it's being quoted or referenced. I think the equalizing that you're talking about is a way to set up a scenario where these disparate things exist in the same world. It's not necessarily the genre that drew me to whichever symbol I picked up.

You mentioned the archive of your great uncle's photographs. What drew you to this archive? Why did you pull what you did?

His name was Kenny Gardner, he was a musician, and he took photos for over five, six decades, and he never really developed them. He had crates full of negatives, and after he died, we were figuring out what to do with them. Sometimes he made contact sheets, but he really didn't print any of it. He died when I was younger, and we brought the negatives back to our house. My aunt, at various times, tried to scan parts of it, and preserve it, and a lot of my earliest work in high school and early college was done from these images. I think a lot of people work from family photographs when they first start painting if they're interested in figurative work.

My husband's a photographer, and I was really interested in getting him to look at the photographs because I always thought that outside of my sentimental family connection to them they were really great pieces of art. He agreed, and offered to properly archive, and safely preserve, all the images. This was around the time we went into lockdown. My husband's practice is all portraiture–mostly shot at his studio–and he obviously couldn't take photos of anyone. Plus the darkroom where he worked shut down for a few months, so he was at home, and really devoted himself to this project; he pretty much scanned everything. Once he was able to get back into the darkroom, he started making real prints from them.

There are a few paintings in the 1969 show that are sourced from my uncle’s archive, like the title painting, ‘Cross the Breeze (2020), and there's another painting in the back of that's called Ear Knot (2020). The other thing that I would say is that Ian and I have been working towards a two person show that's going to happen at Deli gallery next month [It Was Dark in his Arms]. It's both of our work, directly responding to the Kenny photographs. It’s become a really big part of our quarantine experience in the last year.

My husband's a photographer, and I was really interested in getting him to look at the photographs because I always thought that outside of my sentimental family connection to them they were really great pieces of art. He agreed, and offered to properly archive, and safely preserve, all the images. This was around the time we went into lockdown. My husband's practice is all portraiture–mostly shot at his studio–and he obviously couldn't take photos of anyone. Plus the darkroom where he worked shut down for a few months, so he was at home, and really devoted himself to this project; he pretty much scanned everything. Once he was able to get back into the darkroom, he started making real prints from them.

There are a few paintings in the 1969 show that are sourced from my uncle’s archive, like the title painting, ‘Cross the Breeze (2020), and there's another painting in the back of that's called Ear Knot (2020). The other thing that I would say is that Ian and I have been working towards a two person show that's going to happen at Deli gallery next month [It Was Dark in his Arms]. It's both of our work, directly responding to the Kenny photographs. It’s become a really big part of our quarantine experience in the last year.

![]()

Ear Knot (from Kenny Gardner archive), 2020,

oil on canvas, 24 x 18 inches

Your language is really rooted in painting. I’m interested in the relationship you see between photography and painting. Photography can be thought of as a record of something, but a lot of the ways that you render the paintings seem less about representation and more aimed towards an emotive state or a relationship. How has that relationship changed or evolved for you?

There's definitely a back and forth, because I've always worked from photographs.The meaning of that, or what I’m trying to do, has seismically shifted over the time that I've been painting. A lot of that has to do with before this current moment. I completed my undergrad in 2011, and being a figurative or representational painter then, had to be cloaked within this seriousness or conceptual framework. My early work was trying to do something indiscriminate with the sources of my paintings. Now, I feel freer to have romantic flourishes of paint or to be super painterly, to do more intuitive things with the paint. A lot of this has to do with seeing other people doing that and realizing that that's an option.

But I love photography, and, like I said before, my process is rooted in this collecting stage. Often, the thing that sparks interest will be a very minute moment in a photograph or something that suggests a narrative, or maybe a gesture or a facial expression which suggests a color idea. In a material sense, I'm very invested in painting. What I'm thinking about is very painting specific, but photography has an image history in itself. I love the signifiers of that. Whether it's a lighting situation or a cast shadow, it’s one more thing that you can explore. There's a competing interest between the representation and the paint being fully expressed.

But I love photography, and, like I said before, my process is rooted in this collecting stage. Often, the thing that sparks interest will be a very minute moment in a photograph or something that suggests a narrative, or maybe a gesture or a facial expression which suggests a color idea. In a material sense, I'm very invested in painting. What I'm thinking about is very painting specific, but photography has an image history in itself. I love the signifiers of that. Whether it's a lighting situation or a cast shadow, it’s one more thing that you can explore. There's a competing interest between the representation and the paint being fully expressed.

![]()

The gate, 2018

oil on canvas, 72 x 60 inches

I think a lot of the figures have a disconnect from each other, or maybe something distracting them. How important is the act of seeing, metaphorically and literally, in terms of the figures’ gaze and the gaze of the viewer looking at the painting.

That's a good question. A lot of the time there will be figures that stand in for the viewer, like a figure who is also entering the scene, or looking at something that maybe they're telling the viewer to look at. Painting is slow, and a potent part of looking at painting is this slowed down, concentrated way of looking. Painting, or any art that is visual, has its own language. That’s a very deep thing, but maybe this isn't what you're asking.

In terms of thinking about figures interacting with each other in the paintings, it has a lot to do with how I've felt in my life while dealing with or trying to process my own anxieties and fears. It’s this purgatorial waiting space, which is a scenario that I continue to come back to. The act of looking has a narrative quality to it, because it suggests different zones–a before and an after.

In terms of thinking about figures interacting with each other in the paintings, it has a lot to do with how I've felt in my life while dealing with or trying to process my own anxieties and fears. It’s this purgatorial waiting space, which is a scenario that I continue to come back to. The act of looking has a narrative quality to it, because it suggests different zones–a before and an after.

![]()

three, 2019

acrylic and oil on canvas, 50 x 48 inches

three, 2019

acrylic and oil on canvas, 50 x 48 inches

It’s more that we are looking at them, in an almost historical sense, more than they’re engaging with us at all.

Some of the archives that I use or have used in the past few years, have been pretty accessible online, like the ONE Archives. The Gay and Lesbian Center on 13th Street has a library that you can physically visit and go through their archives. Outside of the painting, I have an interest in looking at past queer life. In general, though, the way that I think of the past is as a generative space. I know that my vantage point influences what I see in the images that I'm looking at, I’m not creating anything objective. My painting, and creation of these scenarios, is iterative work. When I find a gesture or a moment from a photograph that really resonates with me I often paint it several times and that has to do with not wanting one specific meaning given to something.

Do you feel like your work allows for the generation of a new personal or historical narrative through the fragmentation and reformulation of images and meanings?

It's new in the sense that it's from my vantage point, and it's reactive in a way. It's always moving, it's always transforming. Even if I set out to plan a painting, that initial narrative usually isn't the one that the work ends up being. It’s important, while you're painting, to be open to those changes, because a lot of the time it's only through that process that you realize what you're truly interested in about this imagery.

It’s a Joni Mitchell song, from Ladies of the Canyon (1970) (but you have to listen to the live versions of it). With the title painting of the show, I was trying to make a group where the circle was protective, those figures are looking at every single direction as a kind of defense mechanism. It’s a very Nicole Eisenman idea, where each figure is its own world. That actually goes to what you were saying about figures in the same composition feeling distant. But for whatever reason, it was really important to me that each figure is an isolated world in itself.

You mentioned somewhere that you were influenced by the Pompeii tiles for Circle Game. Was it more about the visuals of these tiles, or the literal act of excavation that you were interested in?

It’s very entwined. I love the imagery, but there’s definitely a romantic narrative of the city being lost and found and the potential that there's so much more to be found. The thing that always interested me about the famous plaster figures from Pompeii was that they were excavated with a negative process. They kept finding all of these air pockets, and then someone decided to fill it with plaster. It's a reverse method–it was just air basically, like a cast.

On another level, the thing with the Everard [Bathhouse] fires that was also sort of tragic to me, is about the negotiations people made. There was the need for “secret sex,” since it was obviously illegal, and there's the history of gay bars, clubs, and bathhouses being owned by the mafia, so there’s no sort of guarantee that the space is safe. At the Everard, you know, nothing was up to code. It was a fire hazard to begin with. And then there's also this layer to it where the windows were boarded up, which provides protection in secrecy, but was a dangerous situation where people couldn't get out when the fires started. To me, there's a negotiation there that relates to the things that are moving about the Pompeii story.

On another level, the thing with the Everard [Bathhouse] fires that was also sort of tragic to me, is about the negotiations people made. There was the need for “secret sex,” since it was obviously illegal, and there's the history of gay bars, clubs, and bathhouses being owned by the mafia, so there’s no sort of guarantee that the space is safe. At the Everard, you know, nothing was up to code. It was a fire hazard to begin with. And then there's also this layer to it where the windows were boarded up, which provides protection in secrecy, but was a dangerous situation where people couldn't get out when the fires started. To me, there's a negotiation there that relates to the things that are moving about the Pompeii story.

![]()

gay angels, 2018

oil on canvas, 47 x 47 inches

gay angels, 2018

oil on canvas, 47 x 47 inches

I’m connecting the boarded up windows to the previous idea of the gaze and the viewer’s gaze, along with the ways in which you abstract the figures and the relationship to photography. You're taking something that would be completely visible, like a photograph, but you're rendering it in a painterly or even abstracted way. Is this idea of preventing someone from being fully seen related to safety or privacy?

It might be solipsistic, or something closer to the inability to know another person fully, no matter how close you get to them, and then there's also like, an inability to know yourself. From my own mental health, with OCD and anxiety, I don't really trust anything that I’m fixated on, or that the way that I see something is objective reality. That's what a lot of the paintings are. I wouldn't say that they're distrustful of others. It's acknowledging the inability to know someone fully. To go with what you're saying, there's obviously personal and also systemic reasons that you don't know another person fully. That’s probably all there in the paintings.

It seems that most of what we’re talking about is how the past is filtered through your painterly language. How do you think the future plays into the archives and your usage of them?

Most of the work in Burn Across the Breeze, as well as the work that I've been making in the studio since, is future oriented in the sense that it’s grappling with the act of looking back to see that these apocalyptic fears have been consistent throughout human history. Over the summer, I read this book called Doomsday Dreams by Eleanor Heartney about the apocalypse and contemporary art. One of the interesting things she talks about is that at any given time in history, people were thinking about the apocalypse, or could see the signs of it imminently happening. Good people, bad people, anyone across the moral gamut, are able to use the apocalypse or endtime thinking to their advantage.

I've been thinking a lot about the climate crisis this past year, and some think that COVID has a lot to do with the changing weather and deforestation, and that this sort of thing might happen more frequently. So, in a lot of ways, I feel like the work is looking towards the future, and maybe in a fearful way, but I also find past examples of people who also were doing exactly that. So I guess it’s a sort of contradiction, but there's something grounding for me about looking at the apocalypse tapestries, or seeing that this has been a constant existential crisis in the world.

I've been thinking a lot about the climate crisis this past year, and some think that COVID has a lot to do with the changing weather and deforestation, and that this sort of thing might happen more frequently. So, in a lot of ways, I feel like the work is looking towards the future, and maybe in a fearful way, but I also find past examples of people who also were doing exactly that. So I guess it’s a sort of contradiction, but there's something grounding for me about looking at the apocalypse tapestries, or seeing that this has been a constant existential crisis in the world.

![]()

Tapestry Gazers, 2020

oil on canvas, 40 x 40 inches

Before I stop talking about the Circle Game, you say that you're pulling from hagiographic icons, which is something present throughout your work, but it's specifically mentioned in that press release. What significance do the angels and the devils have for you in relation to this queer history?

There was this one icon that I found of a ladder to heaven, and it was a very disturbing scene. There's people climbing a ladder to heaven, and then there are these angel and demon figures pulling them off of the ladder. The thing that was disturbing to me was the way the angels and demons were rendered–they were just silhouettes.They had horns and wings, and it was very confusing about if they're good or evil. I started placing those sort of demons in the paintings, and I thought of them as fate figures, that behind the scenes they might be pulling the curtain or directing what's happening. It was this feeling of lack of control and trying to position that in a painting. So to me, they act as figures of fate. A lot of times, they'll be “x-ray,” or inverted, like they're in the scene, but maybe in a different zone than the rest of the scene.

![]()

arrangement, 2018, oil on canvas, 72 x 60 inches

Okay, actual last question about the Circle Game. The press release talks about Tourmaline’s Q&A about Marsha P. Johnson, and the idea of having the freedom to mythologize or create fantastical elements about something as like a way of pushing back against the impulse that people have to fully know, or prove their history. I was wondering if that relates to your whole body of work. It feels like it's not just about this specific moment in queer history, it feels like it carries throughout your oeuvre.

I think that was like a very significant thing that I learned about around that time, how many artists were working within this structure of critical fabulation. I should say, the actual context of the concept in Saidiya Hartman’s Venus in Two Acts is rooted in Black history and enslaved people. I wouldn't want to say that I'm doing anything as important as that, or to that degree, but it was something that blew open my mind about the idea of the past, which was that it's not this fixed thing.

People have always talked about not 100% trusting a historical source, but what she's asking in that essay is how is it even possible to write about the history of the group of people, if the only historical artifacts of it were written by the oppressors? She was wondering if moving into fiction couldn't be a more truthful way than through recorded history?

People have always talked about not 100% trusting a historical source, but what she's asking in that essay is how is it even possible to write about the history of the group of people, if the only historical artifacts of it were written by the oppressors? She was wondering if moving into fiction couldn't be a more truthful way than through recorded history?

![]()

crowd, 2018

gouache and oil on canvas, 36 x 36 inches

crowd, 2018

gouache and oil on canvas, 36 x 36 inches

Looking at your earlier works, specifically from the ARTHA Project Space show, it seems like the photographic element was very much highlighted. Whereas now, I don’t think it’s as immediately apparent. Is that something that happened naturally or was it a conscious decision?

I think it happened naturally over time. I’ve learned a lot more about color and light. There was a big moment where my logic with those things flipped, where I realized that color and light have as much narrative importance as the setup. Once I started playing with that, the scenes started to develop into their own worlds, divorced from the original photograph. The other thing is that you learn so much from the people around you, and a big influence on how my imagery shifted was, for example, seeing someone like Anna Glatnz’s paintings and how she very mysteriously works through iconography and images. There is a huge freedom in seeing another artist or another friend's practice which gives you permission to do something. I've felt a lot more free to make my recent paintings stranger or to allow unexpected things to happen within them.

It feels like this light is almost submerged or hazy, and creates this very emotive, in-between sense of space. A lot of the scenes are during the night time, and I was wondering if that is related to what interests you about life, or is there a specificity to having these darker spaces?

It's kind of funny, because I feel like one of the first times I painted in that palette, or with that much contrast between, a fluorescent color, and a muddy dark mist surrounding it, I was trying to give myself a painting assignment. So I was like, “what would a night painting look like?” Or, “what does light at night look like?” I was thinking like phosphorescent light, and I feel like that's how that started to come into my paintings. At a certain point, I shifted and realized that the painting is this tactile thing in front of you, and you have the potential to build and create light that emanates from a painting. It's very interesting to think about the painting as a material object.

Especially because you have a body of work with all the vigils, and you’re placing the source of light inside of it. But then the idea of a vigil or candle is creating light within darkness, emotionally and physically.

With that series, I think I only made five of them. Whenever I have an idea for a series like that, I imagine it being like 100 paintings, and it always ends up being like five. I was thinking about them all being in a room together, and they were all sourced from different vigils that I kept finding, because that particular archive was Out Weekly, which is a magazine that was around from about ‘89 to ‘91, it was a New York City gay magazine. That was one of the archives that I was going through a lot before COVID. And it was inevitable because of the time period, but so many of the images were from vigils. In my head, I was like, “oh, when I paint all of these, it's just gonna look like the same event.” So I was thinking about them as on a continuum.

You’ve made a number of zines, which almost directly put your paintings in relation to photography.

Zine-making was much more of my practice before I started grad school. And then I, unfortunately, fell off with that. I went to school for illustration and graphic design, which, in school, it was very easy to do exactly what you wanted to do. The second I graduated, I hated trying to actually freelance as an illustrator. But one of the big things in undergrad that I got involved in was alternative comics, and the zine scene in Brooklyn. After I finished undergrad, I took a step back, and devoted myself to figuring out how to be a painter. But the sensibility from the zines really left a mark, in terms of the overlaying of information in a painting. The way that the symbols overlap comes from how I would pace information on a spread. The way that I thought about zines in the past and pacing them, is connected to how I feel about pacing at an exhibition on a wall, having one painting relate to the first painting that you saw, or an element repeat across all of the paintings.

I want to return more in earnest to the zine-making part of my practice, because I think it's a very unique medium. It gives you as a creator more control of the exact order to look at something. And there's a lot of interesting things it does in regards to pacing, it does compose the work differently if it's in a book or a booklet. That's the equalizing thing that you were talking about, too, which might be tied to what I loved about making a Xerox or risograph book. If I had my own drawing on a spread next to a screenshot of a photograph, next to a graphic bit, when it’s translated, they all have the same weight.

I want to return more in earnest to the zine-making part of my practice, because I think it's a very unique medium. It gives you as a creator more control of the exact order to look at something. And there's a lot of interesting things it does in regards to pacing, it does compose the work differently if it's in a book or a booklet. That's the equalizing thing that you were talking about, too, which might be tied to what I loved about making a Xerox or risograph book. If I had my own drawing on a spread next to a screenshot of a photograph, next to a graphic bit, when it’s translated, they all have the same weight.

![]()

CUT THE WORLD, 2020

oil on canvas, 24 x 18 inches

Do you feel that your and Ian's work influences each other?

Yes, especially now that we're sharing a studio again. He's there for every part of the process for me, and I'm there for every part of his process. Looking back, retroactively, it's like, “oh, wow, we were on the same wavelength about all these things.” I mean, even conceptually, I feel like we're after a lot of the same things. He works almost completely with archives and found images that he then has other people recreate with similar poses. So yes, definitely.

Do you have a dream project?

One of my good friends is a painter, Eric Wiley, we've been friends since we were about 18, and for a while he was very interested in making films. We collaborated on a couple of short films together. I was helping him with this longer one that never panned out, but it’s been years now. So maybe something involving film. I used to watch a lot more film, but I think just because of time that also fell out. I feel like the only things I can watch are things that I don't have to look at.

You reference La Dolce Vita in a past show! Those works feel like snapshots between actions.

I think it’s really good to have jealousy of other mediums. I used to think it meant that I was doing the wrong thing. For example, I love and I'm very obsessed with music, but have literally zero talent in that regard. I always felt like I would rather make an album because I love the album as a medium. I'm very obsessed with how you can relay narrative and themes in an album. I actually think it's way better for that than a painting exhibition, even though that's what I'm trying to do. I always sort of felt this feeling that maybe I wasn't able to do the right thing, but then I read this interview with Cat Power in which she was talking about how she had that exact feeling but wished she could be a painter. I thought, “Okay, if this literal genius thinks this, then maybe it's good to have this weird dangling carrot, or something, in front of you.” It’s a goal to always try for.

![]()

circle game, 2019,

oil on canvas, 48 x 50 inches

Anthony Cudahy and Ian Lewandowski with Kenny Gardner

It Was Dark in His Arms

Deli Gallery, Brooklyn

March 26 – May 9, 2021

Visit Anthony Cudahy’s artist page.

︎: @anthonycudahy