Working from his native Trinidad, Che Lovelace elevates the figures, landscapes, and iconography of the carribean. His works instill the roaming “pothounds,” abundant coconuts, and denizens of Port of Spain with the chromatic energy of the Carnival festival.

In our conversation, the artist and accomplished surfer traces a temporal and geographical map of his intellectual and formal evolutions. Lovelace’s paintings reflect a decades-long exploration of community, family, and identity, a result of both a deep sentimentality and loyalty towards his home, as well as a bright devotion towards innovation.

We chat about the importance of approaching painting through multiple entry points, his choice to stay rooted in his homeland, and the political act of being free to determine how to depict the world around you.

![]()

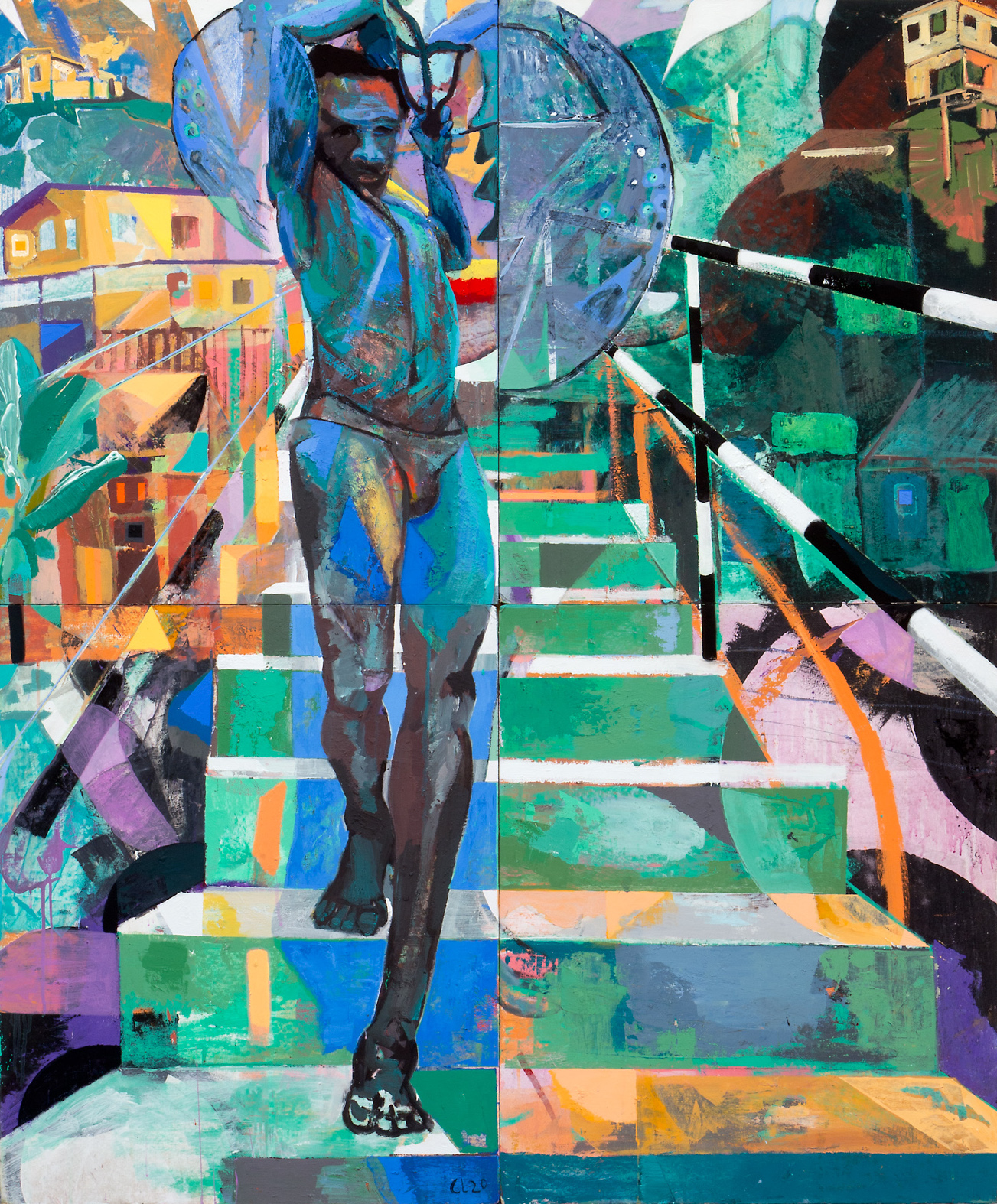

Man Descending Stairs Carrying Wings (to Become a Blue Devil), 2020,

acrylic and dry pigments on panel, 60 x 50 inches

You have an upcoming show in LA?

I do. I started working with Various Small Fires, a gallery in LA, which also has a space in Seoul. It opens March 6th. It's exciting for me and I think for other Trinidadian creatives as it begins opening up possibilities.

Do you like showing other places or do you prefer to show in Trinidad?

Overall, I haven't shown my work a lot. I have shown very little in my career, my life. That is partially because, being in Trinidad, I did not want to get into the cycle of exhibiting art yearly, which is how a lot of artists work here especially if you're working professionally to sell work.

I also felt that my work at that time may have been a bit challenging and difficult to get traction for the Trinidadian audience. My practice has evolved and people understand my work more in Trinidad now, probably because some of the references in my work are now more homegrown.

I have never really been represented by a gallery in Trinidad. I might do a group show here or there, and there was a point earlier on when I did a few residencies abroad. Then, maybe in my early 30’s, I decided that I wasn’t going to apply for residencies anymore. I wanted to stay in Trinidad, to build from this point, to try to discover what can happen here, you know. While I had been here all my life, I still felt there were layers to be uncovered, and those layers had something to do with the physical and cultural environment here.

I guess I just didn't want to distract myself with anything. I said “let me see if I can just buckle down and stay here. However long it takes... we'll do that.” During that time there weren’t many shows at all.

I also felt that my work at that time may have been a bit challenging and difficult to get traction for the Trinidadian audience. My practice has evolved and people understand my work more in Trinidad now, probably because some of the references in my work are now more homegrown.

I have never really been represented by a gallery in Trinidad. I might do a group show here or there, and there was a point earlier on when I did a few residencies abroad. Then, maybe in my early 30’s, I decided that I wasn’t going to apply for residencies anymore. I wanted to stay in Trinidad, to build from this point, to try to discover what can happen here, you know. While I had been here all my life, I still felt there were layers to be uncovered, and those layers had something to do with the physical and cultural environment here.

I guess I just didn't want to distract myself with anything. I said “let me see if I can just buckle down and stay here. However long it takes... we'll do that.” During that time there weren’t many shows at all.

![]()

Tree with Ripe Fruit, 2016,

assorted pigments on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

Earlier, in my mid-20’s, myself, along with a few senior artists, represented Trinidad in international museum shows. Most of that work (which I am still really fond of) came from a series of tapestry-like wall hangings. When I came out of art school, I was quite frustrated, I couldn't really make a painting that I liked. I'm also the type of person who doesn’t like to throw anything away. I went to school in Martinique, and when I came back, I shipped all the stuff that I was working on because I have this belief that everything you touch as an artist, especially if you touch it a lot, has value, because there's a transfer of energy.

So, I kept all that stuff, and I brought it back to Trinidad. I set up a studio with a friend of mine, the painter Eddie Bowen, in Port of Spain. For about two years, I couldn't do anything that I liked. I then started to take apart my work, cut things up, and take things off the stretchers. Soon after, I started to literally sew the pieces back together. That turned into what I considered my first solid body of work, and on the back of that body of work I moved around a bit doing some of these international exhibitions, representing Trinidad. These institutional exhibitions in the 1990’s generally featured various other islands in the region in a dialogue concerned with Caribbean art. These tapestry / wall-hanging works traveled between a few South American countries, and to a couple of other institutions in Europe as well. So that was a little push, and then things kind of settled down–I settled in on the island itself–I kept my fingers crossed, that I could keep alive, you know! (laughs) I guess I have always managed somehow to keep going. I think for artists, generally, if they decide that art is what they’re doing, that it comes with a little bit of a blessing. I've always been on the very edge, but I've always managed to keep a studio and managed to have materials. I've stayed solid enough to keep working.

So, I kept all that stuff, and I brought it back to Trinidad. I set up a studio with a friend of mine, the painter Eddie Bowen, in Port of Spain. For about two years, I couldn't do anything that I liked. I then started to take apart my work, cut things up, and take things off the stretchers. Soon after, I started to literally sew the pieces back together. That turned into what I considered my first solid body of work, and on the back of that body of work I moved around a bit doing some of these international exhibitions, representing Trinidad. These institutional exhibitions in the 1990’s generally featured various other islands in the region in a dialogue concerned with Caribbean art. These tapestry / wall-hanging works traveled between a few South American countries, and to a couple of other institutions in Europe as well. So that was a little push, and then things kind of settled down–I settled in on the island itself–I kept my fingers crossed, that I could keep alive, you know! (laughs) I guess I have always managed somehow to keep going. I think for artists, generally, if they decide that art is what they’re doing, that it comes with a little bit of a blessing. I've always been on the very edge, but I've always managed to keep a studio and managed to have materials. I've stayed solid enough to keep working.

![]()

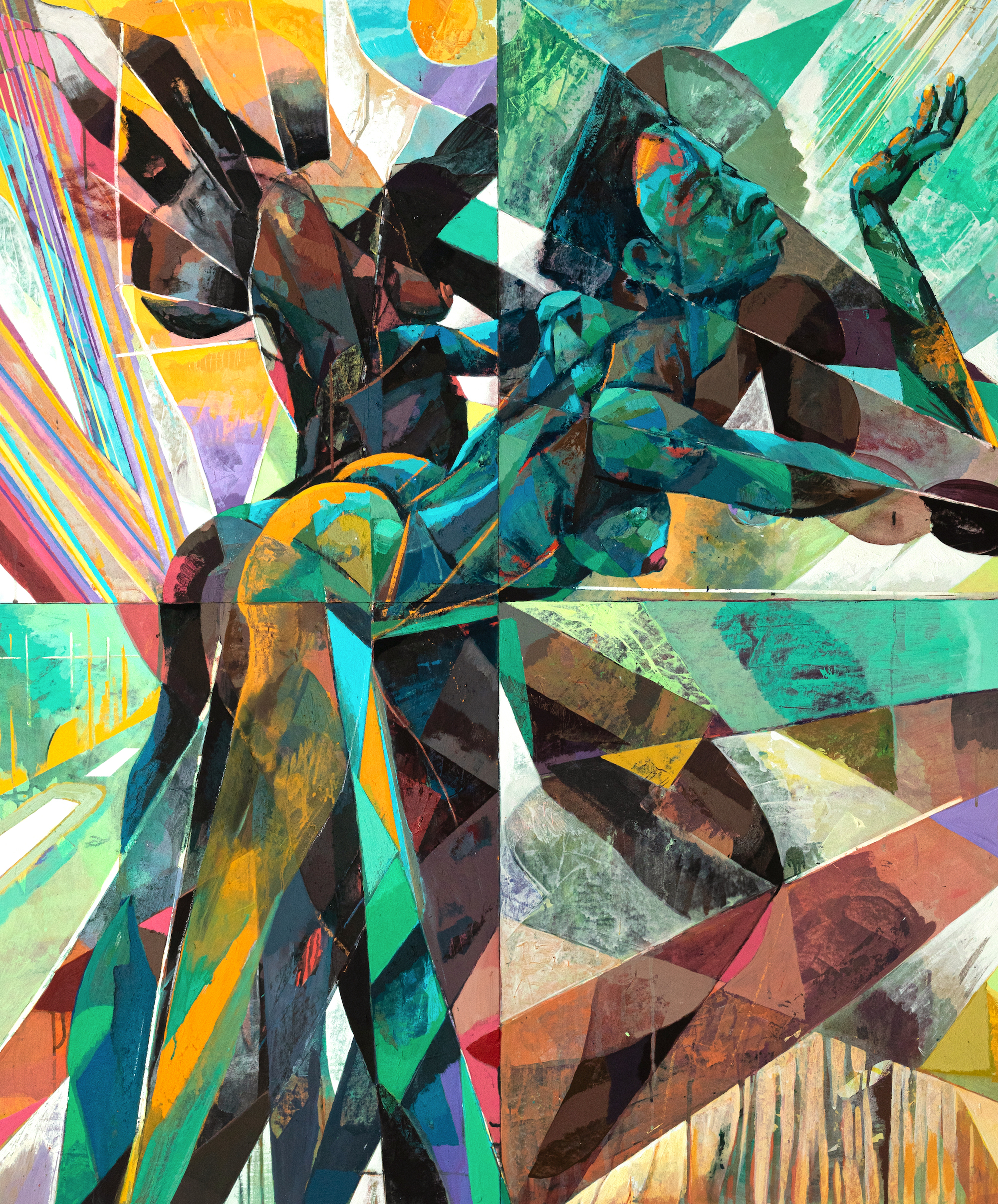

Night II, 2018,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

Recently, I've been showing a bit more, but there have always been long periods without exhibiting. Here in Port of Spain, I tend to work with a gallery or space that I feel is doing something interesting or fresh. A friend of mine opened a gallery a couple years ago, and I liked the space. It was the upstairs of this really cool spot that we would hang out in, where we did these little music events and stuff. I like that context, where people can look at the work in a really relaxed way. So I did two exhibitions in that space, one in 2018 and one in 2019, I believe. Then his gallery closed, I warned him that it wasn't going to be easy! (laughs).

But I'm really happy that I did those shows because they turned out to be two of my most memorable experiences exhibiting in Trinidad. A lot of people saw the work; and the paintings were starting to form a deeper connection with the place, especially in terms of the content you see in Trinidad: the imagery, the people, the color. Things started to come together, it was a nice moment. Because of where we did the exhibition, we could do night viewings as well, so we would stay open late. That was the best experience because a lot of young people saw the work. A good slice of people who saw it, are in fact the folks I would have wanted to see it. That is to say, the younger, or newer creative scene here, or people who are just enthusiastic about the arts whether they’re artists or not. We have a pretty decent sized creative community here, it’s very cross disciplinary.

But I'm really happy that I did those shows because they turned out to be two of my most memorable experiences exhibiting in Trinidad. A lot of people saw the work; and the paintings were starting to form a deeper connection with the place, especially in terms of the content you see in Trinidad: the imagery, the people, the color. Things started to come together, it was a nice moment. Because of where we did the exhibition, we could do night viewings as well, so we would stay open late. That was the best experience because a lot of young people saw the work. A good slice of people who saw it, are in fact the folks I would have wanted to see it. That is to say, the younger, or newer creative scene here, or people who are just enthusiastic about the arts whether they’re artists or not. We have a pretty decent sized creative community here, it’s very cross disciplinary.

![]()

Tree Form, 2016,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 75 x g0 inches

Tree Form, 2016,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 75 x g0 inches

You mentioned that you stopped doing residencies in order to stay where you are and focus, do you feel like you've gotten close to something that you were looking for?

I believe so. I think that it also came as a result of looking more closely at the artists here and immersing myself in the short history of art that we have in Trinidad. Art here really proliferated in the post-World War II era. When I was younger, I knew of some of these artists, and wished to reference them in some way. At that point I didn't tap into them directly, but as time went along, I started to see the value of their work more and more, and I found ways to channel what they were doing. They were, after all, Trinidadian artists, or Caribbean artists, and they were trying to express something about this place, the people, and that moment.

Also, we became independent from the British in 1963, so there was a new interest in identity; bringing alive, rediscovering, or expressing an identity that may have been suppressed during the colonial era. My feeling is that it was more than an ancestral identity, it was an identity in formation–in process– formed from the fragments of this history and shaped from this experience. What does that look like? What does it feel like? So that was kind of their project.

I do feel like a lot of artists coming after that initial strong push and that important moment in painting did not innovate much moving forward. I guess, for me, that golden era for painting here was the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s, even up to the 70’s. What frustrated me when I was growing up was that a lot of the current artists were making repetitions of what the previous group did, right? There was this stable, unchanging form of what Caribbean and Trinidadian art looked like. It became repetitive, and you'd get these typical, predictable Caribbean themes, and a predictable way of painting them, which I found restricting for me as a younger artist.

Also, we became independent from the British in 1963, so there was a new interest in identity; bringing alive, rediscovering, or expressing an identity that may have been suppressed during the colonial era. My feeling is that it was more than an ancestral identity, it was an identity in formation–in process– formed from the fragments of this history and shaped from this experience. What does that look like? What does it feel like? So that was kind of their project.

I do feel like a lot of artists coming after that initial strong push and that important moment in painting did not innovate much moving forward. I guess, for me, that golden era for painting here was the 40’s, 50’s, and 60’s, even up to the 70’s. What frustrated me when I was growing up was that a lot of the current artists were making repetitions of what the previous group did, right? There was this stable, unchanging form of what Caribbean and Trinidadian art looked like. It became repetitive, and you'd get these typical, predictable Caribbean themes, and a predictable way of painting them, which I found restricting for me as a younger artist.

![]()

A Garden with Carribean Artists, 2019,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 50 x 60 inches

I always laugh when I tell people this: in my 20’s, I would never have thought that in my life I’d be painting a coconut. I thought that the coconut paintings that I saw were generally not good paintings, too cliché. Truth be told, I don't think at that point I was good enough to paint coconuts anyway, I don’t believe I would have done a good job. So I stayed clear of it and explored different facets of my identity that were a little bit off the beaten track. I would say, however, that the one thing I never really strayed far from was the body. I was always seeking ways to place the body within the Caribbean context.

Now, further down the road, of course, one of the first things I painted when I came into this new studio in Chaguaramas was a still life with coconuts. I felt something very very strong, I was drawn towards the object. They were big coconuts, and I painted them as large objects, they had this presence and they occupied the space in a different way. It’s been a challenge, and a worthwhile one at that, for me to redefine some of those potentially cliché things in the Caribbean or in Trinidad, to find new life in them.

Now, further down the road, of course, one of the first things I painted when I came into this new studio in Chaguaramas was a still life with coconuts. I felt something very very strong, I was drawn towards the object. They were big coconuts, and I painted them as large objects, they had this presence and they occupied the space in a different way. It’s been a challenge, and a worthwhile one at that, for me to redefine some of those potentially cliché things in the Caribbean or in Trinidad, to find new life in them.

![]()

Still life with Coconuts and Jalousies, 2015,

assorted pigments on board, 50 x 60 inches

I realized that's one of the things that artists can do, you know, we can save clichés, or we can save something from becoming cliché. I have had to navigate that space as I've taken on directly Caribbean themes. Many may seem commonplace or obvious, but they are loaded and worthwhile themes, they always have been. It's just that they were treated in a way that had become a little bit redundant for me in the past.

My earliest oil paintings were quite impasto, I used a lot of painting knives back then, which I've come back to recently. New methods and approaches that take your work forward come with time and space to grow. I didn't wake up and start using boards as my support. It evolved through a bit of necessity and lots of experimentation.

Earlier on, I never accentuated the fact that my large painting surfaces were made up of four board panels. I used to cover the seams and joins. With time, I started to play with accentuating the fragments, the parts, the joint, the mend. Of course, now that I think of it, it seems obvious given the nature of my Trinidadian identity and upbringing, to highlight an integration of parts. I've been using these materials for about 15 years, and I'm still discovering things about them.

My earliest oil paintings were quite impasto, I used a lot of painting knives back then, which I've come back to recently. New methods and approaches that take your work forward come with time and space to grow. I didn't wake up and start using boards as my support. It evolved through a bit of necessity and lots of experimentation.

Earlier on, I never accentuated the fact that my large painting surfaces were made up of four board panels. I used to cover the seams and joins. With time, I started to play with accentuating the fragments, the parts, the joint, the mend. Of course, now that I think of it, it seems obvious given the nature of my Trinidadian identity and upbringing, to highlight an integration of parts. I've been using these materials for about 15 years, and I'm still discovering things about them.

![]()

Nightbird, 2015-20,

acrylic and dry pigments on panel, 60 x 50 inches

I noticed that your dad, the writer Earl Lovelace, also never really left Trinidad. Was that influential in your decision to stay?

That's a good point. He's one of the writers who didn’t leave. Many writers left, you know, for opportunities. It was tough living in a small place and trying to get opportunities, even if you were teaching or whatever it was. He moved around a bit, but this was always his center. I remember growing up listening to conversations between him and friends of his, other artists, talking about Trinidad as the center.

So, yes, that made sense to me automatically. I didn't need to overthink it too much, I knew that this could be a center, because if somebody like him was writing novels here, and creating something that had breadth, a certain scope and bigness to it–even though he was talking about really simple, ordinary things–I thought that it would be possible to do that in any kind of art form. While it might be difficult, and require powers of invention, it was possible.

So, yes, that made sense to me automatically. I didn't need to overthink it too much, I knew that this could be a center, because if somebody like him was writing novels here, and creating something that had breadth, a certain scope and bigness to it–even though he was talking about really simple, ordinary things–I thought that it would be possible to do that in any kind of art form. While it might be difficult, and require powers of invention, it was possible.

![]()

Figure atTreetop, 2016,

acrylic and dry pigments on panel, 60 x 50 inches

“I don't think it was a big thing for me to decide to be based in the Caribbean. The fact is, that even though you're from here, you still have to discover it. That discovery takes a long time.”

The funny thing, from an immigration standpoint, is that I have had the opportunity to leave. My mom worked as a nanny in the states for a while and tried to help us get through school back here in the Caribbean. She would do things that mothers would do, like she would put all her children’s names in the green card immigration lottery, and my name came up one year in the ‘90s. I've had friends in the past who said “why didn't you just go?” I actually tried to live in New York for a bit, but I’d rather struggle here. If I'm going to struggle, let me struggle here–I don't want to struggle in New York.

I don't think it was a big thing for me to decide to be based in the Caribbean. The fact is, that even though you're from here, you still have to discover it. That discovery takes a long time.

But mind you, the intention was never to become insular, or to see this place as a bubble. The intention for me has always been to be part of a larger world, to contribute, from here. To present the Caribbean with the dignity and potential that most people here know exists.

I don't think it was a big thing for me to decide to be based in the Caribbean. The fact is, that even though you're from here, you still have to discover it. That discovery takes a long time.

But mind you, the intention was never to become insular, or to see this place as a bubble. The intention for me has always been to be part of a larger world, to contribute, from here. To present the Caribbean with the dignity and potential that most people here know exists.

Like your father, a lot of your work has this theme of everyday, ordinary scenes.

I do admire artists, or writers who can make ordinary things really come alive, those who surprise you when they have turned whatever they direct their attention to into something grand and almost epic, even in its simplicity. We grew up in the countryside, I didn't grow up in Port of Spain. I grew up in a village called Matura on the east coast. My dad was pretty radical in those days, he didn't have much money, (laughs) still doesn’t, actually. I remember it being a rocky time between my parents, but a friend of his lent us this small wooden house to live in, (which we extended with bamboo over the years) and for 10 years, we grew up on that cocoa plantation with no electricity, living by basic means.

There was an appreciation of the stirring simplicity of things that was ingrained in me very early on, but there was also the magic of it. That's something that I always talk about when people ask me about that period of my life. I don't speak about it as a stressful period, while I know there were hardships. I speak about it as a magical chapter. When I started to go to high school in Port of Spain, I would get up at four in the morning, and that's why I don’t like the mornings anymore (laughs).

There was an appreciation of the stirring simplicity of things that was ingrained in me very early on, but there was also the magic of it. That's something that I always talk about when people ask me about that period of my life. I don't speak about it as a stressful period, while I know there were hardships. I speak about it as a magical chapter. When I started to go to high school in Port of Spain, I would get up at four in the morning, and that's why I don’t like the mornings anymore (laughs).

![]()

Still Life in Studio, 2017,

acrylic and dry pigments on panel, 50 x 60 inches

There was a kind of reverence for the naturalness of the people around me, the common folk in the countryside. There was a very powerful duality going on in our lives, in my life. On one hand, my father, being an intellectual, had friends who would come visit us, like Derek Walcott, Shiva Naipaul, Lawrence Scott, Raoul Pantin and many other writers and artists, and on the other hand, we were living very simply, and our neighbors were sometimes uneducated, or not school-educated, I should say... but who lived with an unadorned grace.

The magic of that duality was always meaningful to how I saw myself, what I valued and thought was important. I have always been moving between spaces, physically and mentally. I can see now how that manifests in my process and shows in my work.

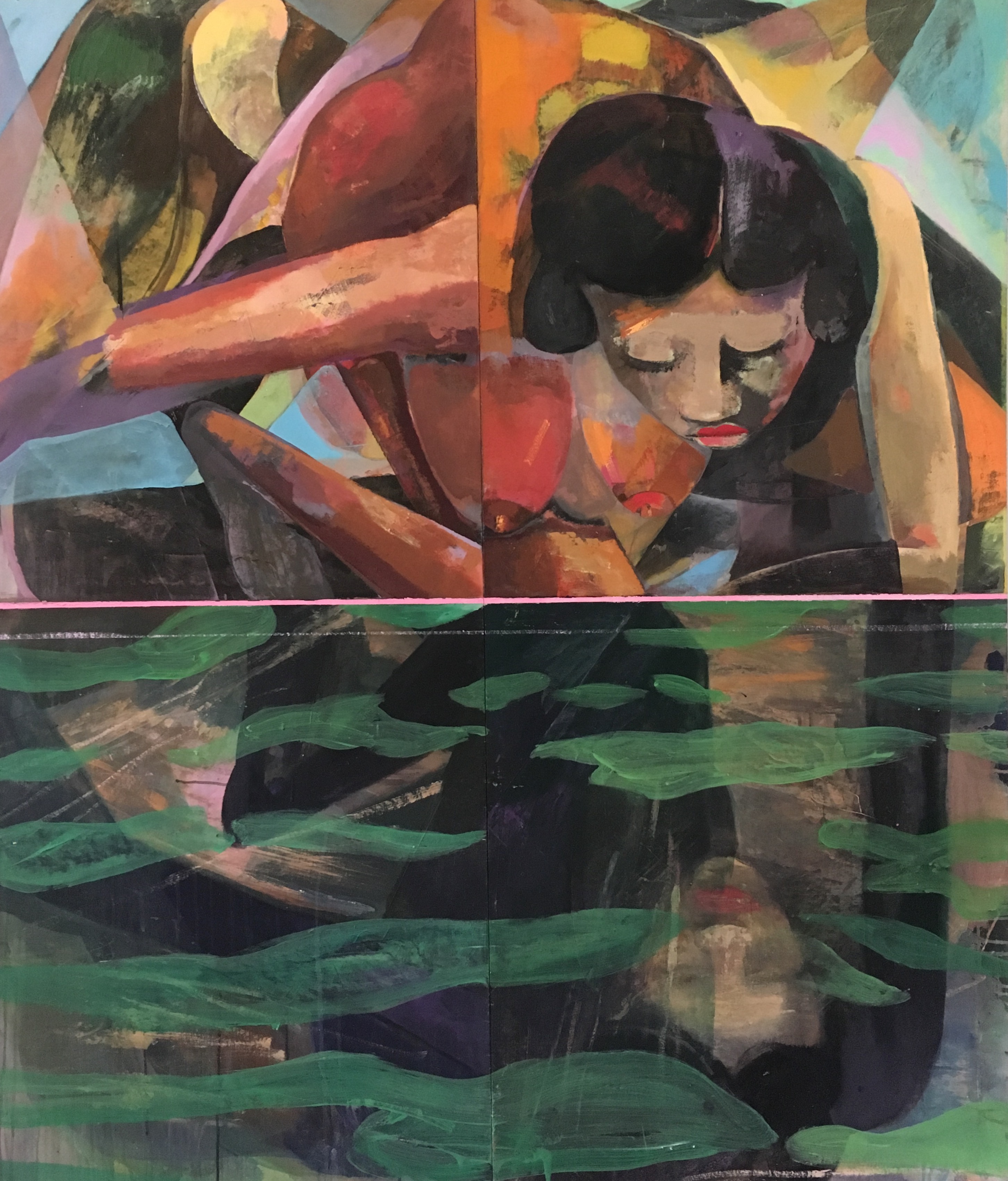

While I also tend to like dramatic themes, like movement and dance, for example, I do love the challenge of coming back to still lifes. I appreciate the intensity of still objects and arrangements and how they can convey emotion and mood….or maybe how mood and emotion can be built around them. There seem to be certain themes that always come back into my paintings, from the human form, dance and movement, to vegetation, and landscape. Not landscape as a pulled back or panoramic view, which we usually associate with landscape painting, but rather the landscape as an immediate, or urgent space. I tend to crop very close up in order to immerse myself in it, and hopefully arrest the viewer to enter as well.

The magic of that duality was always meaningful to how I saw myself, what I valued and thought was important. I have always been moving between spaces, physically and mentally. I can see now how that manifests in my process and shows in my work.

While I also tend to like dramatic themes, like movement and dance, for example, I do love the challenge of coming back to still lifes. I appreciate the intensity of still objects and arrangements and how they can convey emotion and mood….or maybe how mood and emotion can be built around them. There seem to be certain themes that always come back into my paintings, from the human form, dance and movement, to vegetation, and landscape. Not landscape as a pulled back or panoramic view, which we usually associate with landscape painting, but rather the landscape as an immediate, or urgent space. I tend to crop very close up in order to immerse myself in it, and hopefully arrest the viewer to enter as well.

![]()

Season, 2019,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panel, 50 x 60 inches

I am really interested in the image of the stray dog. In one of your Instagram posts you mention that you don't know why you always come back to that subject.

I went to art school in Martinique, which I kind of got into by chance. I wanted to go to art school, and had these dreams of going to Europe, but my parents didn't have money to help enable that. But I spoke with the French consulate in Trinidad and they told me about a school in Martinique, so I ended up going there. There's often a disconnect between Caribbean islands of different languages. So between the English-speaking Caribbean you have some interconnections, while the French-speaking Caribbean would seem further away in many regards. When I was going here, I thought I knew a little French, but when I actually got there, I realized that I didn't know any French! (laughs)

So it was a very intense experience to end up in a new school and a new language. This might seem kind of morbid, but one of the first things I experienced before I had found an apartment, was when I was staying in a student's lodging. There was a courtyard, and one of the first things I saw, on the first or second night that I got there, was this dog. The dog was hurt, and it was a female dog. I just connected with this moment, maybe because I was very alone at that time. I did a few drawings of that dog, I just kind of sat with her. Once I was set up to paint, I did paintings based around that moment... that experience. It became a whole series of dog paintings, actually, that I did between ‘91 and ‘92.

So it was a very intense experience to end up in a new school and a new language. This might seem kind of morbid, but one of the first things I experienced before I had found an apartment, was when I was staying in a student's lodging. There was a courtyard, and one of the first things I saw, on the first or second night that I got there, was this dog. The dog was hurt, and it was a female dog. I just connected with this moment, maybe because I was very alone at that time. I did a few drawings of that dog, I just kind of sat with her. Once I was set up to paint, I did paintings based around that moment... that experience. It became a whole series of dog paintings, actually, that I did between ‘91 and ‘92.

![]()

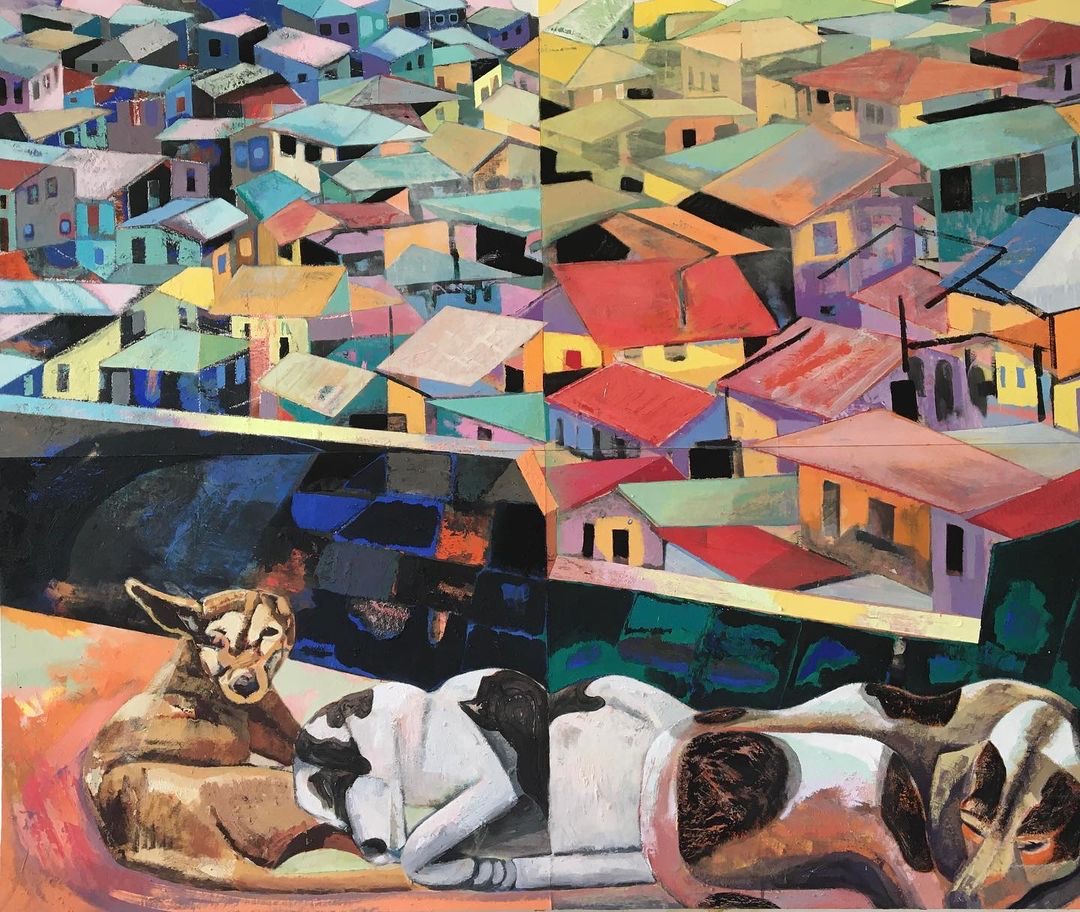

Dogs of Port of Spain, 2020,

assorted pigments on panel, 50 x 60 inches

“There is a type of dog you see a lot in Trinidad, a stray, a mongrel, or what we call a ‘pothound.’ The ‘pothound’ is a dog of mixed origin and an unclear origin, not a purebred dog. To me it has always symbolized something of the makeup and culture of the Caribbean.”

When I got back to Trinidad, on break from my first year, I had done so much work with these dogs, that the go-to contemporary art gallery in Port-of-Spain at the time, called Acquarella, offered to do an exhibition of these paintings. So, you know, back at an early point people thought I had promise, I guess (laughs). They have been waiting ever since!

There is a type of dog you see a lot in Trinidad, a stray, a mongrel, or what we call a “pothound.” The pothound is a dog of mixed origin and an unclear origin, not a purebred dog. To me it has always symbolized something of the makeup and culture of the Caribbean. In this early series I always depicted the dogs in a sort of simplified semi-urban Caribbean landscape.

There is a type of dog you see a lot in Trinidad, a stray, a mongrel, or what we call a “pothound.” The pothound is a dog of mixed origin and an unclear origin, not a purebred dog. To me it has always symbolized something of the makeup and culture of the Caribbean. In this early series I always depicted the dogs in a sort of simplified semi-urban Caribbean landscape.

Yes, we have a lot of pothounds here, and you know, the histories of these societies are fragmented stories. Origins can sometimes be traced, but the destinations that one arrives at are not easily defined. You have different people contesting space, the legacy of slavery and indentureship, the movement of merchants and people selling things. There are a lot of people that arrived here through all these different intertwined histories. So there's something about the mongrel and about the pothound which resonates with the place. It's not a pure place, it's a place that is kind of corrupted (or maybe blessed?) by a lot of different things. And yet, there's a kind of being that emerges... a particular kind of character. The dog, for me, symbolizes that.

When I first started doing them, in those early times, I was a very young artist. In the beginning, the dogs represented a kind of emotional connection to my own state, but as I went along, they became more powerful and began to own and assert their rough-edged presence as well as their own potential. By the end of that year painting these dogs, they started to take on a more mystical aspect. They would be depicted as a small community.

I started painting them as a family with offspring and a mother. I would paint a male dog, or maybe another female, looking at the viewer. They were less curled up, their attitude was changing, they would be a little bit more like, “we might be strays, but we are powerful.” I tried to give them that aura. This period still remains as one of the most memorable times of my artistic life, I was just starting out. I did those paintings predominantly in blues, browns, and darker colors, with a little yellow sometimes.

When I first started doing them, in those early times, I was a very young artist. In the beginning, the dogs represented a kind of emotional connection to my own state, but as I went along, they became more powerful and began to own and assert their rough-edged presence as well as their own potential. By the end of that year painting these dogs, they started to take on a more mystical aspect. They would be depicted as a small community.

I started painting them as a family with offspring and a mother. I would paint a male dog, or maybe another female, looking at the viewer. They were less curled up, their attitude was changing, they would be a little bit more like, “we might be strays, but we are powerful.” I tried to give them that aura. This period still remains as one of the most memorable times of my artistic life, I was just starting out. I did those paintings predominantly in blues, browns, and darker colors, with a little yellow sometimes.

![]()

Carribean Art on Plinths with Dogs, 2021,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

Carribean Art on Plinths with Dogs, 2021,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

And then, funnily enough, at this current studio, some stray dogs started hanging around, but now it's a completely different thing. I am actually not a big dog person. I mean, I like dogs, but I don’t necessarily like the responsibility of owning dogs. If I move around, I'm always thinking, “how am I going to take care of them?” So I shun the responsibility of all that. But they started coming around, and I would keep chasing them. It was always the same three dogs, it was one female and two males. One day, something just clicked and I said to myself, “these dogs are not gonna go away.” I decided I was going to paint them again. It had been decades since I'd painted those dogs of Port de France.

These dogs are now in Port of Spain. My language has evolved, and now I place the dogs within the composition, after much deliberation and moving things around. At first I had them in an enclosed space, then I started to think of them on a kind of plateau, from where you can see the city down below, classic Port of Spain dogs inhabiting a broken abandoned house, an abandoned platform somewhere in the city. It is something that I could imagine... something I would have seen, or that one sees here. So yes, the dogs worked their way back into my consciousness at least for a couple paintings. I actually started juxtaposing the dogs with images of Caribbean art that are displayed on pedestals, as if for sale. It's another offshoot idea that I'm working with.

These dogs are now in Port of Spain. My language has evolved, and now I place the dogs within the composition, after much deliberation and moving things around. At first I had them in an enclosed space, then I started to think of them on a kind of plateau, from where you can see the city down below, classic Port of Spain dogs inhabiting a broken abandoned house, an abandoned platform somewhere in the city. It is something that I could imagine... something I would have seen, or that one sees here. So yes, the dogs worked their way back into my consciousness at least for a couple paintings. I actually started juxtaposing the dogs with images of Caribbean art that are displayed on pedestals, as if for sale. It's another offshoot idea that I'm working with.

![]()

Beetham Protest, 2019,

acrylic and dry pigments on panel, 50 x 60 inches

Beetham Protest, 2019,

acrylic and dry pigments on panel, 50 x 60 inches

Another theme that you seem to return to is Carnival. I noticed the Blue Devils, and then I saw a dragon. I did a little research, and you've also dressed up as a Blue Devil a couple times.

Yeah, I mean Carnival is such a huge phenomenon here. It’s a big reservoir. I have a friend, his name is Peter Minshall, he is the foremost costume designer here, or “Mas Man,” as we say. Amazing man. He was the one who did the costumes for the opening ceremony of the Barcelona Olympics. We're quite close, and he would always say to me, me being a painter, “you know, Che, you need to do the Mas.” That's the word we use...Mas, meaning Carnival, costumes, as well as all the layers and activities that come with masquerading. It's a very complex set of things that identify Carnival. He says, “you know, you're dealing in a dead art form, this ‘Mas’ is the future!” I would always say, “dude, come on, man. Why can't both things live together?” I still insist on that.

I'm actually involved in Carnival in quite a few facets. At the same time, I am committed to painting. One thing doesn't cancel the other. But there's truth to what he says in a way, because Carnival is this very dynamic art form, combining movement, dance, design, color, and sound. It can be quite profound. It is performance oriented, it's ephemeral, it's not about an object. What you get is the experience, what you buy or participate in is the experience.

I'm actually involved in Carnival in quite a few facets. At the same time, I am committed to painting. One thing doesn't cancel the other. But there's truth to what he says in a way, because Carnival is this very dynamic art form, combining movement, dance, design, color, and sound. It can be quite profound. It is performance oriented, it's ephemeral, it's not about an object. What you get is the experience, what you buy or participate in is the experience.

![]()

Mas, 2019,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

“I'm actually involved in Carnival in quite a few facets. At the same time, I am committed to painting. One thing doesn't cancel the other.”

I always say that we are some of the biggest consumers of performance art in the world, because it is a performance art. It's saying, “you can be part of this performance piece,” and people pay money or use resources to be part of it. They don't care that you don't have anything to take home after that. Of course, objects are important, but in this case the object is important only as it relates to the fabric of participation and community.

I tend to play the same character every year... I always play a Blue Devil. It is a traditional Carnival character here. When I say ‘play’, I mean masquerade in costume. So I've been involved in that for many years. I think I always admired the Blue Devil masquerade, but it wasn't until later in my adult life that I really merged with them and started to get involved and perform with them. This also added insight into how I can channel a certain kind of energy into painting. A lot of my work is based around movement of the body, many of the figures you see are performed either by myself or other people. That ability and tendency comes out of the Mas experience, the performative aspect of Carnival. Once I started to perform for my paintings, a new, potent layer opened up. It’s been pivotal in my work, and I feel there is so much scope ahead with this approach, even though I've been developing it in my practice for quite some time.

It is a hands-on way to access an attitude or manner that one sees prevalent in Carnival; the unabashed expressive force of the Caribbean body. And of course, the use of the body historically in a Afro-Caribbean narrative has been connected to self affirmation, communal bonding, as well as resistance to the ownership or control of the body. So performing is a way of getting into a character, and then seeing how that can feed into your work, in order to explore a wider range of possibilities and to approach the subject through an imaginative lens.

It is a hands-on way to access an attitude or manner that one sees prevalent in Carnival; the unabashed expressive force of the Caribbean body. And of course, the use of the body historically in a Afro-Caribbean narrative has been connected to self affirmation, communal bonding, as well as resistance to the ownership or control of the body. So performing is a way of getting into a character, and then seeing how that can feed into your work, in order to explore a wider range of possibilities and to approach the subject through an imaginative lens.

![]()

Emerald and Sun Dancers, 2021,

acrylic and dry pigments on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

I was just watching a lecture on Caravaggio on YouTube, apparently he was one of the first artists to paint himself. When did you start painting yourself?

When I first started making works with my body, they were from photographs, I would take sequential images of little actions and movements. This is when we were still working with film. I would print them out and cut the photos into circles or leave them in their rectangular format. I would then make these medallions from those images and sew them onto a canvas with simple image as a background. That painted image usually related in some way to the action that I was performing in the medallions. I made about twelve of those paintings sometime around the late 90’s. This is why I was saying earlier, you know, that there were some experiences that weren't directly painting experiences, but that it all led to a way of painting.

So that's where the performance part really started, as it relates to creating images. As I started to paint more, this method translated into the painting practice. I started to work with movement, translating movement in the work and using the body in a more dynamic way to get closer to the body subject.

Something artists have always done is look at a subject and try to understand it. They must decide what distance to maintain, depending on what they want to do. Sometimes that is determined by the physical distance from which the artist is painting the subject. I had to ask myself, “how do I see the subject?” Because the subjects were things around me, I saw myself in those subjects as well. So I thought that Carnival and performance was a great way to find myself in those subjects, because this is what we do anyway. So that's why performing became important, even outside of the context of Carnival. The Carnival and performative impulse helped reveal to me that if I can perform these things, I can really try to inhabit them.

So that's where the performance part really started, as it relates to creating images. As I started to paint more, this method translated into the painting practice. I started to work with movement, translating movement in the work and using the body in a more dynamic way to get closer to the body subject.

Something artists have always done is look at a subject and try to understand it. They must decide what distance to maintain, depending on what they want to do. Sometimes that is determined by the physical distance from which the artist is painting the subject. I had to ask myself, “how do I see the subject?” Because the subjects were things around me, I saw myself in those subjects as well. So I thought that Carnival and performance was a great way to find myself in those subjects, because this is what we do anyway. So that's why performing became important, even outside of the context of Carnival. The Carnival and performative impulse helped reveal to me that if I can perform these things, I can really try to inhabit them.

![]()

Girl with Reflection, 2017,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

How does your work involve history, or politics? With the portrait of CLR James, it does seem to be very involved in the politics of Trinidad specifically. Is there a more specific relation there, what drew you to him?

The idea for the CLR piece is something that I spoke about with my father some time ago. It is an idea that exists in his literature. Actually, in his last two books, Salt and Is Just a Movie, he does something similar, which is to have fictional characters doing different things, whether they're politicians, or whether they're common people, in all these various unfolding narratives and stories that are intertwined...but then he would write in actual people that we know into those stories! I always thought that was a very powerful thing, because it jolts the imagination to bring an actual person that you know, whether they’re a historical or contemporary figure, into the world of the novel. He's done that with us, with his children as well... towards the end of Salt there is a passage that describes a march, a kind of protest, among the marchers were ordinary folk, as well as personalities from within Trinidadian culture, and there we were, his children, among those marchers.

The impetus for introducing such an idea to a painting came from there. But it seems like a logical or useful thing to do, to possibly place significant historical figures imaginatively into the fictional world of a painting. Where would they be, what would they be doing? In this case, of course, I had met CLR, as a young boy. He came and spent some time with my family in Matura. He was a fascinating man who spoke fondly of the place and people he came from. Even though he's one of the artists who left the Caribbean, he seemed to always circle back and had deep concern for this region...I always thought about that. So the idea was “how can I locate him back in this place? What would that look like?”

The impetus for introducing such an idea to a painting came from there. But it seems like a logical or useful thing to do, to possibly place significant historical figures imaginatively into the fictional world of a painting. Where would they be, what would they be doing? In this case, of course, I had met CLR, as a young boy. He came and spent some time with my family in Matura. He was a fascinating man who spoke fondly of the place and people he came from. Even though he's one of the artists who left the Caribbean, he seemed to always circle back and had deep concern for this region...I always thought about that. So the idea was “how can I locate him back in this place? What would that look like?”

![]()

Portrait of CLR James, 2020,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

“[J’ouvert is] a very optimistic thing. And yet, it starts in the dark, we’re covered in mud and color; it's this amazing balance of beauty and darkness. We are all equal in this space, and we are all slightly hidden, and thereby really revealed.”

J’Ouvert is this very rooted celebration which opens the Carnival in the wee hours of the morning. It's an activity that I've been involved with for many years, up to the present, organizing what we call a “J’Ouvert band.” I believe there is a kind of magic in it. It’s something that really brings us together and bonds us in that moment, no matter where you're from, all the races etc... It's a very optimistic thing. And yet, it starts in the dark, we’re covered in mud and color; it's this amazing balance of beauty and darkness. We are all equal in this space, and we are all slightly hidden, and thereby really revealed.

So I thought that this is the place you'd want to welcome anybody who is coming home... who's coming back from a far away place. I don’t imagine them sitting in a chair, in a veranda with old friends, I would want them on the street, with the energy of that J’Ouvert moment. So that's why I thought that would be the place to paint CLR in a homecoming picture.

So I thought that this is the place you'd want to welcome anybody who is coming home... who's coming back from a far away place. I don’t imagine them sitting in a chair, in a veranda with old friends, I would want them on the street, with the energy of that J’Ouvert moment. So that's why I thought that would be the place to paint CLR in a homecoming picture.

In terms of politics, you know, the political is embedded in so much of what we do. The way one chooses to live exists in contrast with another way of life or way of thinking. Unpacking that always reveals the dynamics of identity and therefore politics. I've never thought of the political in a very direct way in my work. Honestly, I feel that the ability to be free, in terms of how you depict the world around you, is a political act. The idea of evading categorization is a political act, especially as a coloured or Caribbean person. I think because of the state of the world, people are expected to express their politics and identity in predictable or stereotypical fashion. The fact that I'm not trying to do that is a political act, it's about an attitude and a way of seeing that is very important for me.

I am interested in expressing my own sense of identity, place, and community in complex and nuanced ways. I see that as a place of discovery and possibilities and not one of static definitions. So in a loose but important way, you can tie that back to something political.

Of course when a figure like CLR James enters a painting I'm also evoking what he stood for. I'm happy to evoke what he stood for; his thinking, how he saw this region, how he saw the world, how he saw people. I'm joining somewhat with that when I depict him, I'm celebrating that. Artists and writers are an important group of people for this region, especially in a place where politics has failed in many ways. It's the cultural life that has kept these places going and kept them so alive and buoyant. So the pivotal figures and personalities deserve that kind of treatment, to be reflected and immortalized.

I am interested in expressing my own sense of identity, place, and community in complex and nuanced ways. I see that as a place of discovery and possibilities and not one of static definitions. So in a loose but important way, you can tie that back to something political.

Of course when a figure like CLR James enters a painting I'm also evoking what he stood for. I'm happy to evoke what he stood for; his thinking, how he saw this region, how he saw the world, how he saw people. I'm joining somewhat with that when I depict him, I'm celebrating that. Artists and writers are an important group of people for this region, especially in a place where politics has failed in many ways. It's the cultural life that has kept these places going and kept them so alive and buoyant. So the pivotal figures and personalities deserve that kind of treatment, to be reflected and immortalized.

![]()

The Tuning Yard, 2020,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 50 x 60 inches

We were talking a lot about time earlier. How important is time to your process?

I think one of the most important discoveries that I have made about my work, or maybe things have just evolved that way, is that paintings now take a lot longer. Maybe I found a way to slow down the process to the benefit of the painting. I find that I need to have a series of entries into a painting at different periods of time for it to really reveal its full possibility. So having many beginnings is important. What I do in the studio is that I have several things going on.

This year, for example, quite a few of the paintings that I finished were started three years ago, and I've been working on them consistently, putting them down for periods, before once again putting them up on the studio walls and trying to push them forward. It's almost like I don’t want to take them to completion too quickly, even when I think I see a window to do so. Prolonging seems to offer more opportunity for clarity. These additional periods of time have become crucial in order to be confident with the shapes and combination of colors that are being developed in the work. At its core, the question seems to always be “what areas should be left alone, and what areas should be built up?” I have often worked up an entire painting to suit, fit, or correspond to one area of the surface that I like. I am also fond of digging into a stack of slightly earlier work and pulling things out that I feel are not quite resolved. I may then work on these pieces, introducing new ideas, while sometimes keeping elements of the earlier composition that I like.

This year, for example, quite a few of the paintings that I finished were started three years ago, and I've been working on them consistently, putting them down for periods, before once again putting them up on the studio walls and trying to push them forward. It's almost like I don’t want to take them to completion too quickly, even when I think I see a window to do so. Prolonging seems to offer more opportunity for clarity. These additional periods of time have become crucial in order to be confident with the shapes and combination of colors that are being developed in the work. At its core, the question seems to always be “what areas should be left alone, and what areas should be built up?” I have often worked up an entire painting to suit, fit, or correspond to one area of the surface that I like. I am also fond of digging into a stack of slightly earlier work and pulling things out that I feel are not quite resolved. I may then work on these pieces, introducing new ideas, while sometimes keeping elements of the earlier composition that I like.

![]()

Drum Spirit, 2021,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

“Maybe I found a way to slow down the process to the benefit of the painting. I find that I need to have a series of entries into a painting at different periods of time, for it to really reveal its full possibility. So having many beginnings is important.”

There seems to be more of a continuity in a lot of the things that I've been doing, at least over the last 7 years or so. Before that, I worked through a series of shorter, tighter periods exploring different things. Time has been very very important to develop the ideas and string together all those various experiences, which at a different point may have seemed disjointed, but which I now realize were in fact crucial to arrive at where the paintings are currently. It's almost kind of scary to think about making work quickly now.

With what I'm trying to achieve now, there are still fast moments in the painting, there are areas where you can see that it’s one layer of paint. But it’s also about “how am I framing that? How am I having that moment live with the rest of the painting?” So the painting is usually oscillating between these quick moments and more labored sections. I need a lot of time for that to be sorted out. So, yes, time is very important.

With what I'm trying to achieve now, there are still fast moments in the painting, there are areas where you can see that it’s one layer of paint. But it’s also about “how am I framing that? How am I having that moment live with the rest of the painting?” So the painting is usually oscillating between these quick moments and more labored sections. I need a lot of time for that to be sorted out. So, yes, time is very important.

In terms of reference, it seems like you draw from a ton of different places. Going through your instagram, I noticed you mentioned El Greco, Seurat, and Van Gogh. Is there any part of art history that you're particularly drawn to? Is it closer to an almagamation?

I think what I was saying earlier about, you know, looking at things from a very wide lens is also true about my personality in general. So I tend to not block things out, I tend to come from a position of curiosity and embracing things. I'm not trying hard to do that, I think it's a natural way. So I do look at the world with a sort of openness, an openness that I expect would affect me.

While that may carry over to how I approach looking at art, early on, I seemed to be drawn to certain artists. I was always drawn to El Greco because I have always been attracted to elongated figures in art. I don't know where it came from, it’s the same thing with Munch. I was drawn to him from the minute that I saw pictures as a young boy in high school. Maybe we are born with certain sensibilities before we learn or are exposed to others. There is a melancholy in Munch that made me feel alive.

The journey of looking and being open as one matures becomes the place from where new and different sensibilities or aesthetics begin to affect us. It is useful to examine art that you are not automatically attracted to. For me, this has added layers of comprehension regarding new possibilities of painting and what those paintings may look like going forward.

While that may carry over to how I approach looking at art, early on, I seemed to be drawn to certain artists. I was always drawn to El Greco because I have always been attracted to elongated figures in art. I don't know where it came from, it’s the same thing with Munch. I was drawn to him from the minute that I saw pictures as a young boy in high school. Maybe we are born with certain sensibilities before we learn or are exposed to others. There is a melancholy in Munch that made me feel alive.

The journey of looking and being open as one matures becomes the place from where new and different sensibilities or aesthetics begin to affect us. It is useful to examine art that you are not automatically attracted to. For me, this has added layers of comprehension regarding new possibilities of painting and what those paintings may look like going forward.

![]()

Bongo Dancers, 2021,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

“The journey of looking and being open as one matures becomes the place from where new and different sensibilities or aesthetics begin to affect us. It is useful to examine art that you are not automatically attracted to.”

Somebody like Paul Klee has become more and more important for me. I find the way that he approaches creating fascinating. The mysterious process of putting fragments together, and starting to sort of nurture something, and seeing how it's going to grow...and of course the tenacity to stick to it.

He's also helped me to bring together a lot of the influences that are homegrown. There's an artist here called Leroy Clarke, who is a very grand, older artist now, who makes an abstract, almost geometric and afrocentric kind of art. I've known him since I was a small child, he's a friend of the family, and I've always admired his work even though I struggled to find out how his paintings could affect my approach. More recently I'm finding myself being able to understand his work a lot more, the strength of certain lines, his use of pyramidal forms, and geometries.

He's also helped me to bring together a lot of the influences that are homegrown. There's an artist here called Leroy Clarke, who is a very grand, older artist now, who makes an abstract, almost geometric and afrocentric kind of art. I've known him since I was a small child, he's a friend of the family, and I've always admired his work even though I struggled to find out how his paintings could affect my approach. More recently I'm finding myself being able to understand his work a lot more, the strength of certain lines, his use of pyramidal forms, and geometries.

I think it’s starting to come across in my work. That geometry is now marrying with a straightforward or naturalistic depiction of the figure. Something like this exists in the work of some of my favorite Trinidadian painters, like Sybil Atteck and Carlisle Chang. Ultimately, I am interested in paintings that occupy multiple worlds simultaneously, or paintings that exist in that moment of transformation between one style to the next. I think of the moment when certain abstract expressionists were on the cusp between figuration and abstraction...forming a bridge between the two. Arshile Gorky and Willem De Kooning are good examples of painters who straddled two spaces, especially the paintings they made throughout the 1930’s. Closer to home, the original savant-like artist Embah, was a master of threading between magical worlds in his art.

But with regards to influence and references, I was thinking recently that at some point, in order to find out what you possess as an artist, the act of painting has to be an act of forgetting, rather than remembering. This then leaves you completely free.

My father gave me two books when I was quite young, when I decided I wanted to be an artist. One was on the Expressionists, and the other was on Cubism. I don't think he plotted that, but he must have felt something. He must have said, “okay, expressionism makes sense, you want expression in your work.” And Cubism involves an abstraction of form and thought. So ultimately I think they were two strong poles to start out with. And in fact, I think I can see them in my work now.

But with regards to influence and references, I was thinking recently that at some point, in order to find out what you possess as an artist, the act of painting has to be an act of forgetting, rather than remembering. This then leaves you completely free.

My father gave me two books when I was quite young, when I decided I wanted to be an artist. One was on the Expressionists, and the other was on Cubism. I don't think he plotted that, but he must have felt something. He must have said, “okay, expressionism makes sense, you want expression in your work.” And Cubism involves an abstraction of form and thought. So ultimately I think they were two strong poles to start out with. And in fact, I think I can see them in my work now.

![]()

Boy in Undergrowth, 2018,

acrylic and dry pigment on board panels, 60 x 50 inches

︎: @chelovelace