Having lived and worked in Edinburgh, Australia, and, most recently, Portugal, the exact “location” depicted in a painting by Danny Leyland may or may not be immediately recognizable. For a painter concerned as he is with the emanation and accruing of meaning, his experiences sit alongside broader ideas of place. It is the confluence of forces like the physical, historical, archeological, mythological, colonial, or personal contexts that is made visible in the work. In this vein, it is of no small import for Leyland that context extends quite outside of the canvas and towards the history of where, when, and by whom paintings are viewed.

When we met with him over Zoom, we pondered together over a conception of artmaking that is not altogether removed from the present, of course, but certainly more expansive and penetrates deeper than the “artworld” at present often leads us to believe is possible.

When we met with him over Zoom, we pondered together over a conception of artmaking that is not altogether removed from the present, of course, but certainly more expansive and penetrates deeper than the “artworld” at present often leads us to believe is possible.

![]()

![]()

![]()

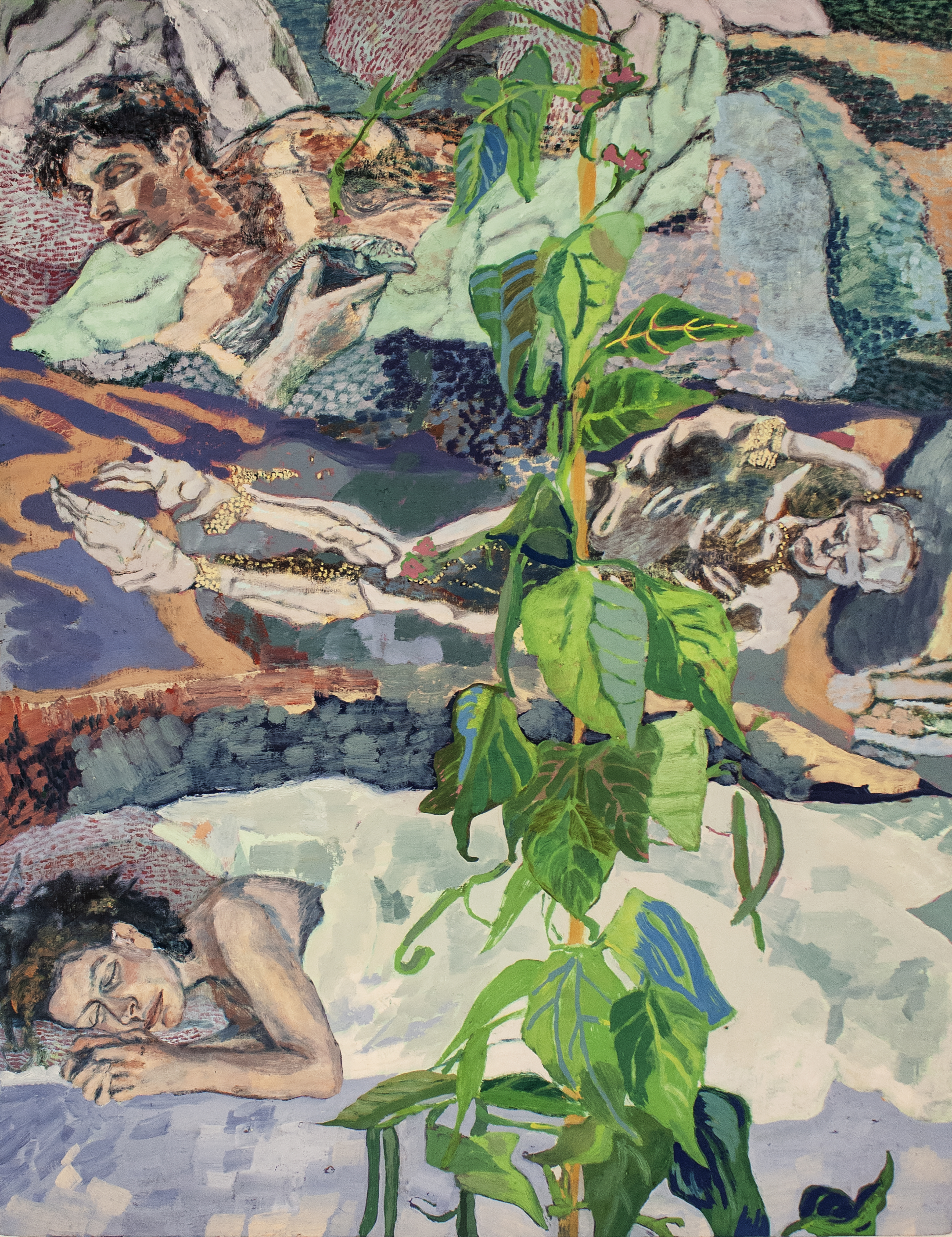

Mistress of Animals, 2025

oil on canvas, 115 x 145 cm

Have you been working on a new body of work for your upcoming show?

In October I moved into a new studio in London. At first I was in a bit of a funny place. I had come back from this residency at PADA in Barreiro, Portugal, and I wasn't particularly happy with the work I made there. I wasn’t sure how to begin fitting together a body of work for this upcoming project at Mare Karina, Venice.

I don't know how to begin talking about the work but perhaps I can show you?

I would love to see it; Yeah, definitely.

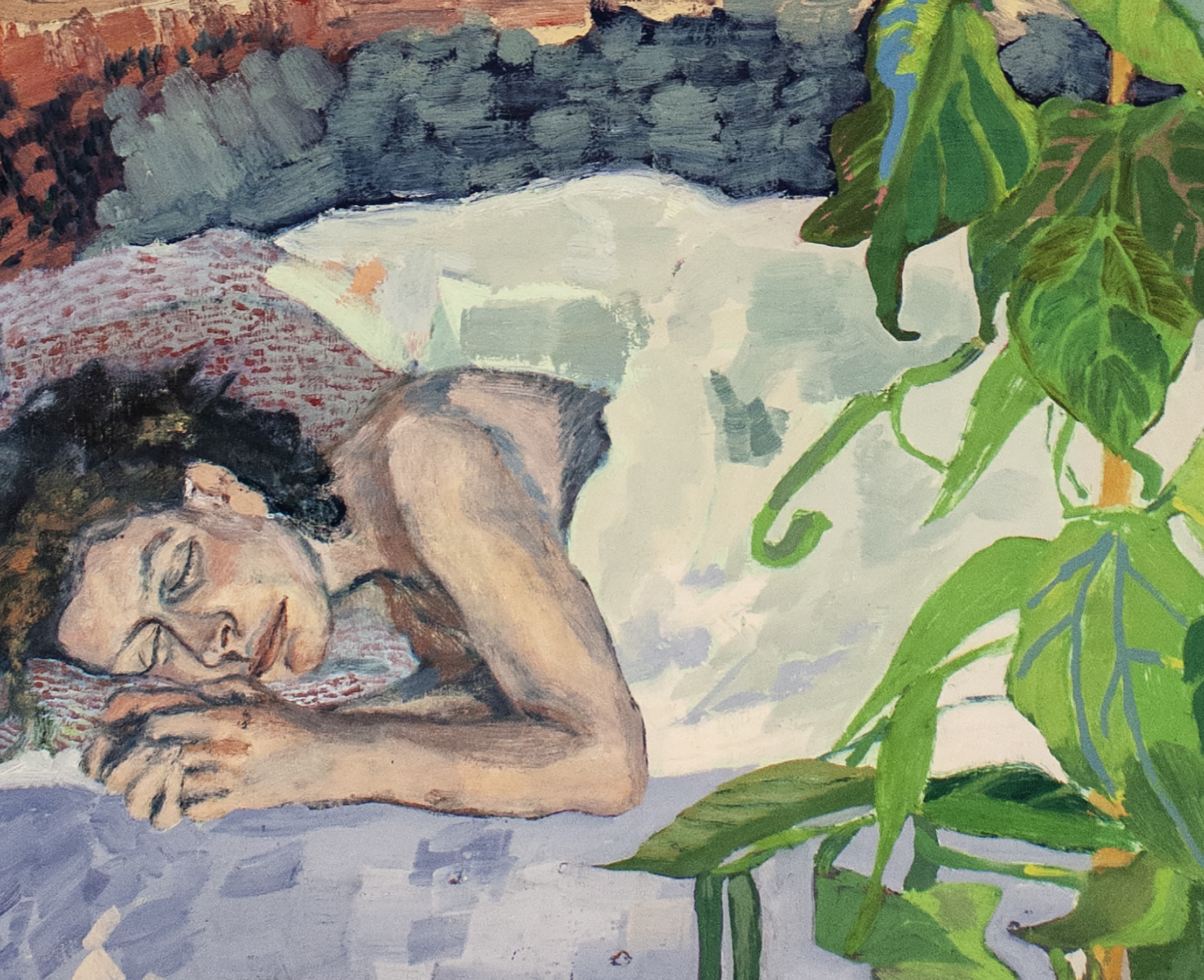

This is the one I've been working on today [Mistress of animals, 2025]. The central image is of a figure embracing this tiger lying down.

And then I have this one as well [The art of not being seen, 2025]. This is one of the paintings I began in Barreiro, it’s of two figures sitting in a boat and beneath them there are a number of objects that are aligned in a grid or a sort of cabinet formation.

And then I have this one [Gravesend girl, 2025], which is not that developed, actually, but there's a kind of toy train ride at the bottom, and a taxidermy thylacine in the top corner.

And then I have this one as well [The art of not being seen, 2025]. This is one of the paintings I began in Barreiro, it’s of two figures sitting in a boat and beneath them there are a number of objects that are aligned in a grid or a sort of cabinet formation.

And then I have this one [Gravesend girl, 2025], which is not that developed, actually, but there's a kind of toy train ride at the bottom, and a taxidermy thylacine in the top corner.

The taxidermy figure–is that a Tasmanian Tiger?

Yeah, it’s the Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine. There are many accounts of people seeing them in the wild even though they're extinct. It’s fascinating that people still feel their ghostly presence in the landscape. It reminds me of the legend of the fen tiger around Cambridge where I used to live. There are these stories of tigers being sighted in the fens, usually by farmers or anglers, and it’s become a sort of modern legend. I think it speaks to some kind of longing for a vanished wilderness. The fens as a landscape doesn’t really exist anymore. The vast wetlands were drained and reclaimed for farming a long time ago.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Gravesend Girl, 2025

oil on canvas, 130 x 95 cm

The painting with the grid of the vases and objects [The art of not being seen, 2025] feels very museological, is that related to your interest in archeology in regards to the idea of the archive and preservation?

Yeah, that image came from this photograph of the interior of a storage unit of Jacopo Medici’s collection of illicit, black market looted antiquities. In a way, that's been the sort of central point of interest for the rest of the works. It really hit a chord, because I have quite a personal connection to museums. Museums have always meant a lot to me, but at the same time, I recognize that they play, or have played and continue to play a key role in this colonial exchange of ideas, or transactional way of viewing objects that is also akin to painting.

I felt challenged by that on many levels, even on the level of being someone who likes to paint images and things and objects. There is a tradition in oil painting of being able to render the surface of something, of painting as illusion, or being able to capture the essence of an object for a viewer’s pleasure, which is also transactional in a way.

The grid of the storage cabinet also seemed to offer a convenient visual device, a way to organise the painting. The grid-like compartments made me think of how images appear on our screens.

I felt challenged by that on many levels, even on the level of being someone who likes to paint images and things and objects. There is a tradition in oil painting of being able to render the surface of something, of painting as illusion, or being able to capture the essence of an object for a viewer’s pleasure, which is also transactional in a way.

The grid of the storage cabinet also seemed to offer a convenient visual device, a way to organise the painting. The grid-like compartments made me think of how images appear on our screens.

The art of not being seen, 2025

oil on canvas, 140 x 110 cm

You mentioned in another interview the Piero Della Francesca painting, The Baptism of Christ. It was a light bulb moment for me, I feel like I gained an understanding of your work. Knowing that you have a particular interest in archaeology and the ancient and medieval worlds, I began to think about the way that images would or could function then and how it is so wildly different from what images can do now. Images as devotional versus commercial objects on a gallery wall, for example.

That's hit so many different points that I'm interested in! The National Gallery in London has two fantastic paintings by Piero Della Francesca, The Baptism of Christ and The Nativity. I think It was the baptism which I felt closest to at first, with its pale, central Christ figure sort of looming out of the painting. It felt so immediate and so close to me, like an encounter with a ghost of someone I knew.

Later I watched this video online about the conservation of The Nativity. They pointed out a couple of scorch marks on the painting’s surface that were made by candles. The painting was part of Piero’s own household where candles were placed in front of it, and so it was used in this practical, everyday kind of way, which makes it an object of focus for an incredibly personal kind of interaction.

At times I really struggle to find a connection to painting, and when I see work in the world it doesn't necessarily move me. I’m too aware of its materiality, how much space it's taking up, how much money it's worth, these prosaic things. Where you can interrupt that, maybe, is in a domestic or more personal context—when you give a gift of art to a friend, or you receive something, handle an object, or inherit something from a relative, then it creates its own context. That Piero painting, The Nativity, absorbed all of these memories from being in the household over many generations, absorbed the intensity of all that concentrated looking over time. The scorch marks on the surface are a record of that.

Later I watched this video online about the conservation of The Nativity. They pointed out a couple of scorch marks on the painting’s surface that were made by candles. The painting was part of Piero’s own household where candles were placed in front of it, and so it was used in this practical, everyday kind of way, which makes it an object of focus for an incredibly personal kind of interaction.

At times I really struggle to find a connection to painting, and when I see work in the world it doesn't necessarily move me. I’m too aware of its materiality, how much space it's taking up, how much money it's worth, these prosaic things. Where you can interrupt that, maybe, is in a domestic or more personal context—when you give a gift of art to a friend, or you receive something, handle an object, or inherit something from a relative, then it creates its own context. That Piero painting, The Nativity, absorbed all of these memories from being in the household over many generations, absorbed the intensity of all that concentrated looking over time. The scorch marks on the surface are a record of that.

“...when I see work in the world it doesn't necessarily move me. I’m too aware of its materiality, how much space it's taking up, how much money it's worth, these prosaic things. Where you can interrupt that, maybe, is in a domestic or more personal context—when you give a gift of art to a friend, or you receive something, handle an object, or inherit something from a relative, then it creates its own context.”

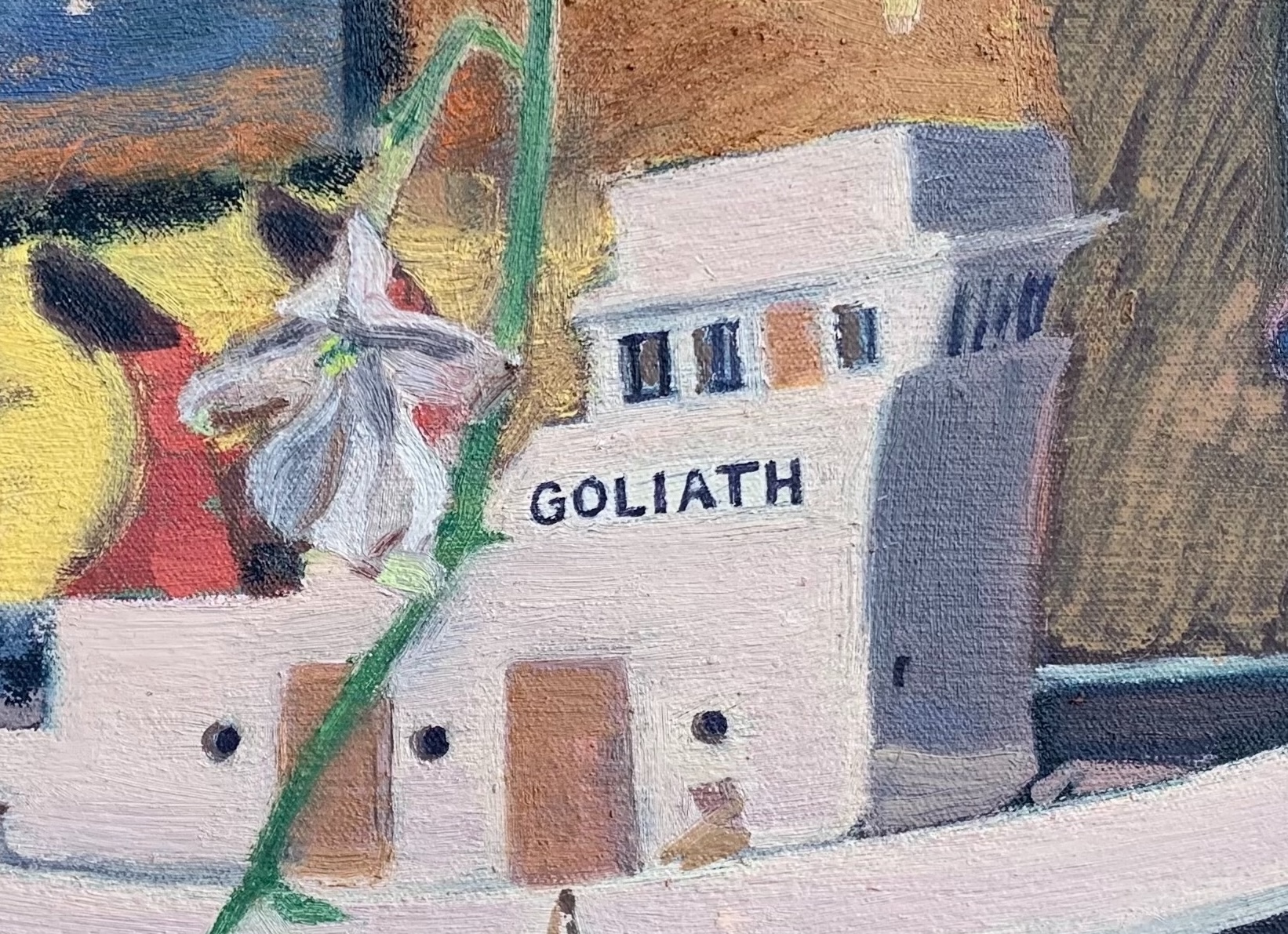

It’s interesting that you mention inheriting an artwork, because you have that painting [Look to Windward, 2021] with the model of a fishing vessel built by your great-grandfather as a present for your uncle. It’s like you're trying to bring in that sense of the personal, even though you know the work is going to be in a commercial context.

In my studio I’ve all these objects lined up on the window sill, things I was given, or picked up in charity shops, or found on the street. This is a ceramic coin that an artist called Jame St. Findlay made. I just have these things and I try to bring them into the work sometimes. It’s a way to create systems of meaning.

![]()

![]()

Look to Windward, 2021

oil on canvas, 30 x 40 cm

Look to Windward, 2021

oil on canvas, 30 x 40 cm

It seems like you have this inclination towards almost primordial or elemental representations of fire or smoke or water.

What I enjoy looking at and find moving in other people's work is when there's a sort of numinous experience captured through the everyday, or something that is kind of restrained but which, because of that restraint, has a quiet power that comes through. It often feels like a balance between finding a certain image that accrues meaning to itself but which doesn’t insist on meaning something in particular. I’m thinking about the images in Elizabeth Bishop’s poems. That’s had a great influence on me.

It seems like time itself is also really central to your practice. You’ve previously talked about trying to tap into the moment just before something happens, and you're also dealing with archeology, which has an element of deep time. Your compositions have these images that are inherently really layered and you find all of these different ways of creating meaning towards the layers which allow for multiple points of entry.

I think that comes from the journey I've been on. While studying in Edinburgh I was really interested in mythology, and then a bit later, I became interested in archeology as well. The UK has such a fantastically complex and layered landscape. When you go walking there are these pockets, maybe a stone avenue or a burial mound, where time seems to collapse and you are suddenly amidst a version of space and time that feels quite different. It can be a pretty haunting, powerful experience.

I definitely had this sense, this consuming sense, really, that older things were more honest or authentic or pure, that there's this original reality in the ancient world that I could aspire to understand or emulate.

A key text for me at the time was The White Goddess by Robert Graves. I read it as if it was all completely true, this wild universal theory about ancient religion, and I tried to apply its morality to my life. I was fully engaged with that urgent Modernist project of trying to find connections between everything (though of course I didn’t understand it in that way). It took me a long time to recover from its effects!

Since then I've been able to contextualize that feeling. And realise that there is no such thing as an unbroken link to an unchanging past, a version of Britain that is more original or authentic than any other. That the past contains not one but a multiplicity of narratives.

I definitely had this sense, this consuming sense, really, that older things were more honest or authentic or pure, that there's this original reality in the ancient world that I could aspire to understand or emulate.

A key text for me at the time was The White Goddess by Robert Graves. I read it as if it was all completely true, this wild universal theory about ancient religion, and I tried to apply its morality to my life. I was fully engaged with that urgent Modernist project of trying to find connections between everything (though of course I didn’t understand it in that way). It took me a long time to recover from its effects!

Since then I've been able to contextualize that feeling. And realise that there is no such thing as an unbroken link to an unchanging past, a version of Britain that is more original or authentic than any other. That the past contains not one but a multiplicity of narratives.

A Pearly King, 2021

oil on canvas, 80 x 61 cm

“The UK has such a fantastically complex and layered landscape. When you go walking there are these pockets, maybe a stone avenue or a burial mound, where time seems to collapse and you are suddenly amidst a version of space and time that feels quite different.”

Speaking of the past, looking at the history of your work, it seems like there's a jump between your Bricolage series and The Burial Paintings in terms of the compositions. You’ve talked about looking down from an airplane and seeing the land as a quilt, and in the early works the composition is almost full of patchwork and patterns. Then in The Burial Paintings, there’s a similar sense of pattern and color, but you’ve really opened up the composition, it's not quite so tightly packed. It feels like you’ve allowed the surface to have more depth and space to breathe. I was wondering what that jump was like for you.

I don't know. I made the “burial paintings” around the lockdown, when I was living in a more rural area and generally in a bit of a downer period. They definitely feel quite different. I wish I had gathered more of those works together, and had the chance to develop them as a body of work and perhaps present them together. But I worked on them in quite a scattered way, late at night after teaching, without ever quite realising what I was getting at. The paintings ended up being quite an enigma and perhaps not very successful. Looking back on them they do feel overly tight, and the idiom is weirdly romantic.

The way that my practice evolves often strikes me as a bit erratic, and that's something I fret about a bit, actually, as an artist. I wonder if by now I should be able to make more of a cohesive body of work, but every painting I make seems totally different, as if it’s the first painting I’ve ever made. I often look back at my work and I'm like, wow, did I really make that? Or what was I doing there? But then again, I’m pretty allergic to artists who make the same kind of paintings again and again.

The way that my practice evolves often strikes me as a bit erratic, and that's something I fret about a bit, actually, as an artist. I wonder if by now I should be able to make more of a cohesive body of work, but every painting I make seems totally different, as if it’s the first painting I’ve ever made. I often look back at my work and I'm like, wow, did I really make that? Or what was I doing there? But then again, I’m pretty allergic to artists who make the same kind of paintings again and again.

The Smith, 2019

oil on canvas, 121 x 198 cm

How do you think place influences the body of work that you're making?

It comes through in the burial paintings and other work I had made before then. When I moved to Australia in 2021, however, I immediately felt that my practice had to change, because the land there is not mine, it's not part of my history. I don't have any claims over it, nor should I. My perspective had to change quite radically, and I turned to documenting the things that were around me in the most immediate sense. I increasingly used more of a collage-like process, which lent a feeling of displacement to the work; displacement in a visual and spatial sense, created as a result of images from different places and times coming into a single pictorial space. I realised that certain images seemed to fascinate me more than others, and so I worked with them again again, stretching their possibilities. I tried not to question it any more than that.

I think that this process has lingered since I've moved back to London, and through my residency in Portugal as well. For example, the toy train was something that I saw in the supermarket in Barreiro. It’s a children's toy train that has this big plastic Native American figure, but it's in the supermarket in Portugal, so it has this character of displacement about its situation. The Native American girl reminded me of the story of Pocahontas, who left her homeland and died in Gravesend on the east coast of England. So there's this narrative of change and just a sort of visual oddity in that.

I think that this process has lingered since I've moved back to London, and through my residency in Portugal as well. For example, the toy train was something that I saw in the supermarket in Barreiro. It’s a children's toy train that has this big plastic Native American figure, but it's in the supermarket in Portugal, so it has this character of displacement about its situation. The Native American girl reminded me of the story of Pocahontas, who left her homeland and died in Gravesend on the east coast of England. So there's this narrative of change and just a sort of visual oddity in that.

Hunters of the black swan, 2024

oil on canvas, 90 x 120 cm

oil on canvas, 90 x 120 cm

That feels closely linked to what you're getting at with the other painting of the stolen objects, the movement of objects and their displacement from their context.

What do you think lulls, or creative blockages do for you? Do you find them generative? I recall in our email thread, when you were in Portugal, you were not feeling in tune with your practice. I’m interested in how that resolved itself, if it has.

What do you think lulls, or creative blockages do for you? Do you find them generative? I recall in our email thread, when you were in Portugal, you were not feeling in tune with your practice. I’m interested in how that resolved itself, if it has.

It's a really interesting question. It's something that I talk about a lot with my students and teacher-colleagues, this idea of being stuck as a really creative place to be, because it's all about a place of unknowing, and there's a sense of limitless possibility, and you have to somehow deal with that. What do you do next when you can do anything? It can be pretty crippling. I'm not sure painting always has to be fun, I mean no job is always going to be fun, but I sometimes wish it would be a bit more fun.

A longing for rain, 2024

oil on canvas, 90 x 120 cm

How does writing figure into your practice as a painter? You pull from literature and folklore for your paintings, and then you also have a writing practice, and I'm wondering if it buttresses or supports your painting, or if you see them as totally separate?

Well they're connected by me and so the interests are shared. I definitely do find it helpful if I have a poem turning over in my brain over the course of a few weeks; the way that it’s slowly chiseled into shape is akin to painting, in the way that they can combine different things, images, perspectives, and then through a sort of distillation they become something completely new, which has its own sort of set of meanings.

Do you ever have an audience in your mind when you're working on a painting, or is it really more of a solitary or expressive act?

For this project I’m currently working on, a small solo presentation at Mare Karina Gallery in Venice, there's a connection between the work and the context of that place, Venice being this early medieval city that was the center of vast maritime empire, the heart of a nexus of trade routes where artifacts like those in the paintings were accumulated and presented, so it seemed like a sort of natural home to explore these ideas. The right audience with which to have these conversations.

When awake I’m just drifting, 2023

oil on linen, 120 x 90 cm

You mentioned in an Instagram post the idea of “thin” places. I was wondering if painting for you is a thin place. I feel like there's a lack of that in our world at the moment.

That's a mythological motif from Celtic stories, especially associated with water, this idea of the thin places where the other world seems closer. Actually, the painting The Baptism of Christ by Piero Della Francesca we were discussing earlier, that could describe an encounter with one of the thin places. The Christ figure seems to have one foot in reality and one foot in the world of the spirit. The thin river curling across the centre of the painting could be a divisionary curtain between the two worlds.

I don’t know, definitely on a good day that's the sort of place that I'm trying to approach when I’m painting. One foot in each world. But we can’t achieve that on a daily basis. Most of painting is probably about plodding on, one step at a time.

I don’t know, definitely on a good day that's the sort of place that I'm trying to approach when I’m painting. One foot in each world. But we can’t achieve that on a daily basis. Most of painting is probably about plodding on, one step at a time.

︎: @danny_leyland