An ethos of unification undergirds Ficus Interfaith, made up of artists Ryan Bush and Raphael Cohen. Together, they adhere to a way of thinking, talking about, and making art on a first person plural level. And for the two of them, Ficus Interfaith takes on its own entity, or a third distinct voice. This central factor of their practice extends to their primary medium of terrazzo, itself a composite material which is used in lobbies, public spaces, and homes all over the world. As a vernacular material, there is already implicit meaning in terrazzo’s use as an artwork, and that’s where Ficus Interfaith steps in—to play with and question how certain objects, spaces, words, and histories came to mean what they do.

For almost ten years, Ficus Interfaith has been posting to My Brother’s Garden, a shared archive and vault of poems, entire Wikipedia pages copied and pasted, Youtube videos, images, and miscellaneous content from the internet. (An embedded Youtube video of the PS 22 choir performing Katy Perry’s Fireworks is the earliest post, dated December 8, 2014 at 4:21 pm). The site also serves as their artist website in a more conventional sense, where they post past exhibitions, press, and images of their work. Among the probably hundreds of poems on the site is “Miracles” by Walt Whitman, posted on Saturday, May 16, 2015, at 4:03 PM. In typical Whitman fashion, he lists all of these beautiful sights and experiences like wading “with naked feet along the beach just in the edge of / the water.” But it’s not just these things as discrete experiences which make them miracles, it’s that “…These with the rest, one and all, are to me miracles, / The whole referring, yet each distinct and in its place…”

We spoke with Ryan in the duo’s studio in Queens while Raphael called in from his parents house upstate.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Grandfather Clock, 2022

cementious terrazzo, deer bones, brass, 82.75 × 21 × 1.5 inches

Courtesy of Deli Gallery

Nice to meet you. How is it up there?

It's very nice up here, I just worked in the garden a little bit. There was a frog and two toads.

I don’t know if I can tell the difference.

Toads are bigger and wartier.

Toads are bigger and wartier.

Yeah, the frog is slimy and wet, toads are fatter and wartier and dry,

Toads don't like water, right?

You can see it on them; the frogs are glossy.

Warts are associated with toads, because they're all warty. There's an old wives tale that if you touch a toad, that's how you get warts on your fingers.

[He proceeds to venture to the garden to find and show everyone the frogs and toads, but gives up before going back to the house]

So you met at RISD, and you both received BAs in painting. How did you end up moving on to terrazzo as your main medium?

When we started working together, it felt like sculpture was just an easier avenue to do as a collaborative practice, because painting can be so intuitive and most painters operate in a solo pursuit. I think the common thread going through it was trying to find materials that were maybe deemed part of a waste stream in some way, or have an aspect of reuse in the sculpture. We were researching the history of mosaics. We stumbled into terrazzo, which also has a history of reuse and recycled material. And then that was that.

Ryan showed us some of your watercolors earlier and he said that with the watercolors, you can see your specific hands in each of them, but then once you’re working in terrazzo, it’s like a third hand.

I think that it’s really different from painting. There’s an element of craft that involves many steps, which allows us to lose our hands in a way that's really enjoyable, as opposed to painting which is probably the most immediate way to make art. It's just your hand, your mind, color, and the paint itself. With the terrazzo we've found the process so rewarding, because there's just so many steps that you can share in a way.

Do you both always have a hand in each work?

We make every creative decision together, which is exhausting, but it's not that hard. We do every single thing ourselves. Physically, there are things we do hand off. Raph’s more precise than me and more of a perfectionist. I rush and I take shortcuts, so Raph always does the colors, because he's better at that, and I do all the emailing. There's certain things that we have figured out.

“Most often with craft objects, they’re unattributed or they'll be attributed to a time or a culture. We think that’s fascinating, as opposed to a work of art being the product of a single person's funnel of ‘artistic genius.’ I think that we're interested in that murky space.”

I feel like the distinction between art and craft is present and alive, but also not that important. I'm wondering if you see this distinction as something that you are playing with, not necessarily breaking it all down, but having fun with.

Yeah, absolutely. One thing that really stands out to us when we go to the museum is the decorative arts versus the fine arts, and how they're categorized and attributed. Most often with craft objects, they’re unattributed or they'll be attributed to a time or a culture. We think that’s fascinating, as opposed to a work of art being the product of a single person's funnel of “artistic genius.” I think that we're interested in that murky space. That's why Ficus Interfaith—naming it—has been really helpful, because it's not an equal part Raph and Ryan and our individual lives and trauma. Of course, those things feed into the art, but it's Ficus making art as Ficus, versus us telling our own stories.

A lot of your earlier works had plaques which were attributed to “Ficus Interfaith Research & Properties.” Do you still include those on every work?

No—but we should. I don't know why we left that, but we sign each work as Ficus Interfaith, and it doesn't matter who signs it.

I haven't thought about those in a while, but I think we were using them when the works that we were making looked more like art. Things like furniture or craft use those plaques as a label or attribution, and that was a way of confusing the kind of product that we were making. Once we started making tables and furniture, it became unnecessary to confuse it more. Or maybe it was more obvious to use a plaque at that point, so then we stopped using it. It wasn't a decision that we made, I think it happened naturally.

I haven't thought about those in a while, but I think we were using them when the works that we were making looked more like art. Things like furniture or craft use those plaques as a label or attribution, and that was a way of confusing the kind of product that we were making. Once we started making tables and furniture, it became unnecessary to confuse it more. Or maybe it was more obvious to use a plaque at that point, so then we stopped using it. It wasn't a decision that we made, I think it happened naturally.

![]()

Plow (detail), 2017,

powder coated steel, custom plaque, dimensions variable

Courtesy of Gern en Regalia

You’ve described your show Grand Central Tree House [2023] at Deli, as really momentous since it was your 50th exhibition together. Can you talk about what made it feel so important?

I don't think the show itself stands out as a marker, so much as it was us checking in with ourselves about what we have done and what we want to do. In terms of the work, that was us pushing the limits on what we could do scale-wise. Those are the largest works we've ever made, and the first time that we've ever made something that just us two couldn't carry. There's a symbology in that, and it speaks to collaboration and what it means to think creatively beyond yourself both physically and mentally. Making art that you literally cannot carry alone–what does that mean?

I think it was also the first time we really showed furniture and art together in a gallery space. We wanted terrazzo tables and terrazzo wall works that operate essentially as paintings right next to each other. That's something we're still interested in, because it had become two forks of our practice: one being commission based work that tends to be furniture and flooring, and the other one being artworks that hang on the wall. Part of the terrazzo project is also pushing the material and technique within the format, using branches or oyster shells or fruit pits. It's exploring those alternative techniques in both formats and then seeing how they operate differently or together.

There was a lot going on in that show. There was a pushing of the material, and there were also a lot of references—historical references, playful references—with the pool table and the Roman skeleton mosaic. So the title of the show kind of came after all of the works, but I think the overarching idea is in the title of the show itself. It speaks to Grand Central being this big, public historical space, and the tree house being a vernacular, private space, and then what happens when you jam them together.

I think it was also the first time we really showed furniture and art together in a gallery space. We wanted terrazzo tables and terrazzo wall works that operate essentially as paintings right next to each other. That's something we're still interested in, because it had become two forks of our practice: one being commission based work that tends to be furniture and flooring, and the other one being artworks that hang on the wall. Part of the terrazzo project is also pushing the material and technique within the format, using branches or oyster shells or fruit pits. It's exploring those alternative techniques in both formats and then seeing how they operate differently or together.

There was a lot going on in that show. There was a pushing of the material, and there were also a lot of references—historical references, playful references—with the pool table and the Roman skeleton mosaic. So the title of the show kind of came after all of the works, but I think the overarching idea is in the title of the show itself. It speaks to Grand Central being this big, public historical space, and the tree house being a vernacular, private space, and then what happens when you jam them together.

Popcorn Curtain, 2023

popcorn, brass curtain rod, dimensions variable

Courtesy of Deli Gallery

And you had the popcorn curtain.

Yeah.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Installation view, Grand Central Tree House, 2023

Deli Gallery, New York, NY

Courtesy of Deli Gallery

It’s interesting, because it seems like the focus on these ephemeral materials was more prevalent early in your practice, before terrazzo became your main medium. I was wondering what is your interest in the difference between the relative permanence of those materials?

I think at this point, it's so refreshing to make art that's not so heavy and permanent. Back to the difference between Grand Central Station and a tree house. A tree house is a place where you play and imagine and everything falls apart. It’s associated with child’s play and pretending, and the popcorn feels part of that camp. Also the work in ferrocement that's literally all falling apart is part of that. My favorite thing is to imagine the terrazzo existing far from now, once our identities become erased in the same way that the popcorn fell apart. I think that's how they're connected.

At a time, what was enticing about terrazzo was that it was so permanent. Because, you're right, we had previously worked with such ephemeral materials. I mentioned the interest in mosaics before, one of the things that was interesting about mosaics was its permanence and monumentality, this idea that there's something that you make that outlasts you and can be read in different ways in different time periods, versus something that kind of decomposes or falls apart. Now that we've been using terrazzo so long, it's fun to do things that are compostable.

At a time, what was enticing about terrazzo was that it was so permanent. Because, you're right, we had previously worked with such ephemeral materials. I mentioned the interest in mosaics before, one of the things that was interesting about mosaics was its permanence and monumentality, this idea that there's something that you make that outlasts you and can be read in different ways in different time periods, versus something that kind of decomposes or falls apart. Now that we've been using terrazzo so long, it's fun to do things that are compostable.

The permanent / impermanent interest marries a lot of the subject matter that you’re engaged with. Between the natural world as subject matter and terrazzo itself being this highly permanent substance. Are you posing any questions or problems about the permanence or impermanence of nature?

A lot of the imagery we use comes from the “interfaith” part of comparative mythologies, and a lot of the things we look at for inspiration are very ancient. Through that, there's this material hierarchy of rocks from a geological standpoint. If you're an anthropologist or a geologist, you're both studying rocks essentially because rocks last the longest, so they have the most potent stories. Wood is next, and then maybe fabric.

It becomes this linear way of thinking about our relationship to changing nature, where you've carved a rock and that lasts thousands of years, versus making a meal which lasts a day or a moment. That's what we think of as a way of zooming way out, and then zooming way in, and then disrupting it with, say, a Spongebob reference, which doesn’t really relate.

It becomes this linear way of thinking about our relationship to changing nature, where you've carved a rock and that lasts thousands of years, versus making a meal which lasts a day or a moment. That's what we think of as a way of zooming way out, and then zooming way in, and then disrupting it with, say, a Spongebob reference, which doesn’t really relate.

Spongebob, 2024,

cementious terrazzo, 24 x 18 x 1.25 inches,

Courtesy of the artists

cementious terrazzo, 24 x 18 x 1.25 inches,

Courtesy of the artists

Right, there are a lot of cultural allusions and references too.

In Grand Central Tree House, we had Pinocchio (Sentimental Prick), being made of wood and becoming human and then another piece featuring Daphne, a nymph who is turned into a tree. Both subjects have wood chips as terrazzo aggregate, frozen in different moments of humanness.

Materially, we're trying to acknowledge responsibility for what types of materials we're using, while also being realistic. I hope that instead of being preachy about the environment or climate change, it's more about responsible ways of interacting in nature, which doesn't necessarily mean preservation all the time. Sometimes work that involves itself with or talks about the environment can have an unrealistic message in terms of how humans can exist.

Part of what I like, and that I think we are successful at, is that, yes, there’s natural material, branches, and waste, and things that fold back into the work, but not in a way that deems it like the only option. And there's also playfulness. I think the cultural references are part of that, not everything can be about saving the forest necessarily, but that doesn't mean you have to chop it all down at the same time.

Those graffiti remnants from ancient Rome that people just love because they're irreverent, we feel that in the studio—that sense of irreverence and also humility. When we first started making terrazzo, we had this idea that maybe someday we'll make a terrazzo with moon rocks or diamonds. We’re way less interested in that now. It's almost a form of exoticism and we’ve moved onto better things.

We talk a lot about the difference between something that's genius and ingenious. And we've thought that an ingenious use of materials, for example, is when you are able to use what you have available, versus arriving at an idea through mental capacity. Not that we're geniuses, but whenever we're getting too smart, we think, “okay, are we being tricky, and for who and why?” regarding our material choices, and what we’re deciding to make.

Materially, we're trying to acknowledge responsibility for what types of materials we're using, while also being realistic. I hope that instead of being preachy about the environment or climate change, it's more about responsible ways of interacting in nature, which doesn't necessarily mean preservation all the time. Sometimes work that involves itself with or talks about the environment can have an unrealistic message in terms of how humans can exist.

Part of what I like, and that I think we are successful at, is that, yes, there’s natural material, branches, and waste, and things that fold back into the work, but not in a way that deems it like the only option. And there's also playfulness. I think the cultural references are part of that, not everything can be about saving the forest necessarily, but that doesn't mean you have to chop it all down at the same time.

Those graffiti remnants from ancient Rome that people just love because they're irreverent, we feel that in the studio—that sense of irreverence and also humility. When we first started making terrazzo, we had this idea that maybe someday we'll make a terrazzo with moon rocks or diamonds. We’re way less interested in that now. It's almost a form of exoticism and we’ve moved onto better things.

We talk a lot about the difference between something that's genius and ingenious. And we've thought that an ingenious use of materials, for example, is when you are able to use what you have available, versus arriving at an idea through mental capacity. Not that we're geniuses, but whenever we're getting too smart, we think, “okay, are we being tricky, and for who and why?” regarding our material choices, and what we’re deciding to make.

Daphne, 2023,

cementitious terrazzo, zinc, branches 44 × 44 × 1 1.5 inches

Courtesy of Deli Gallery

So your focus is on using what you already have or what's there already?

Yeah, trying to use it in a way that no one else thought of, versus “wow, I never thought of that.” It has to do with what's available. There's a certain resourcefulness that is most important to us.

The way we operate is that you can make a more beautiful thing with the overlooked material that's already around you, versus the rarest material that you have to import. It may take a little bit more transformation, but it's a more rewarding experience to look at.

The way we operate is that you can make a more beautiful thing with the overlooked material that's already around you, versus the rarest material that you have to import. It may take a little bit more transformation, but it's a more rewarding experience to look at.

![]()

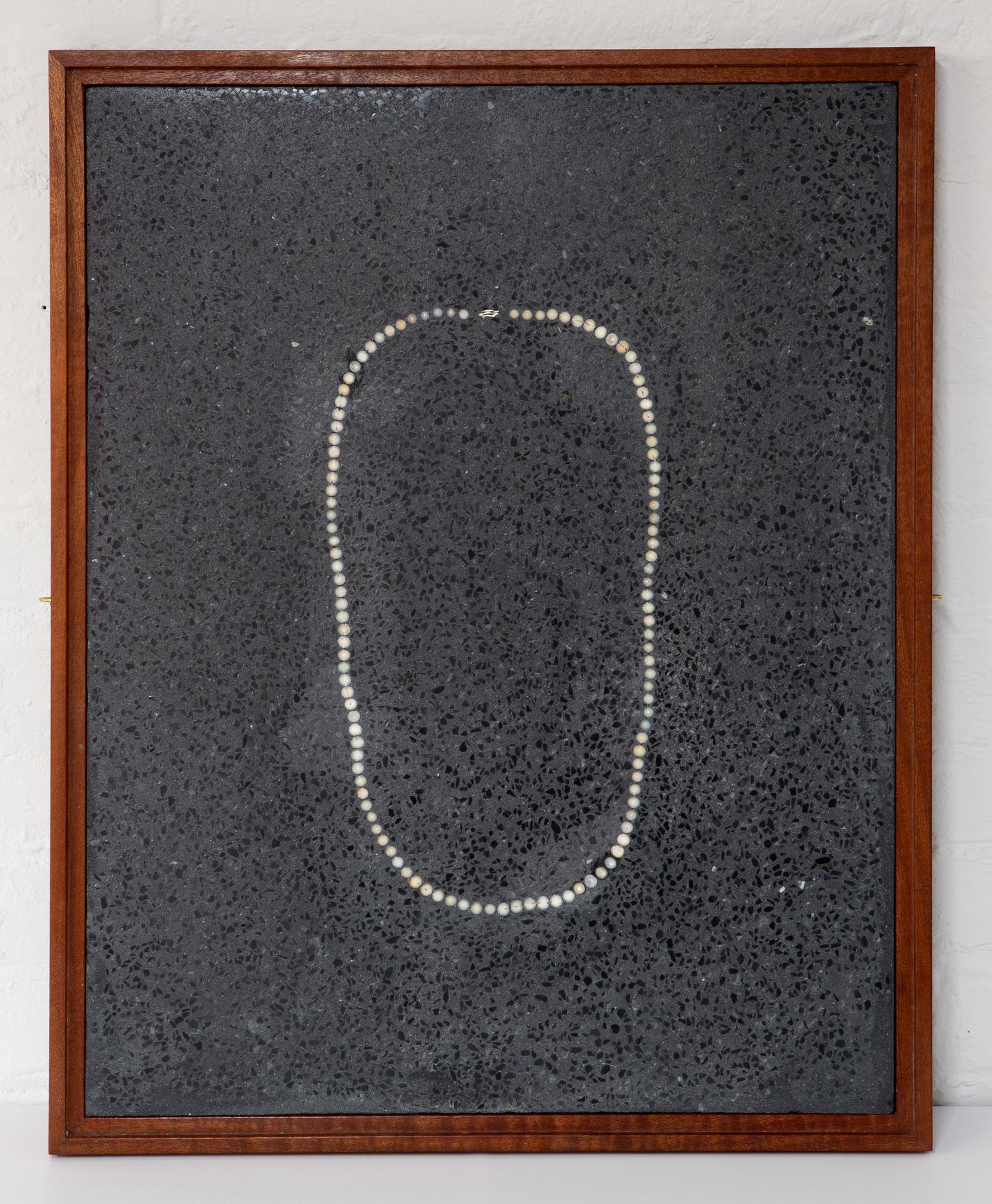

Pearl Necklace, 2024,

cementious terrazzo and pearls in wood vitrine, 25 × 19.75 × 2.25 inches

Courtesy of Deli Gallery

You used the word vernacular before to refer to spaces but this relates to materials as well.

We're really attracted to when that vernacular gets disrupted, like with the invention of plastic, for example, how dramatically that changed things. Or when cultured pearls became a thing. For thousands of years, only someone like a king would have a pearl, and cultured pearls just dismantled that hierarchy, and when suddenly, anyone could have pearls, and then their perceived value changed.

That makes me think of the fact that on Earth we see diamonds as this incredibly rare, valuable material, but if you look at it on a universal scale, it's actually incredibly common in comparison to pearls, which require oysters, which are not everywhere, but we don’t see them as having the same value.

I think that's so beautiful. There's this Tiktok (sorry) where they talk about that, how on a universal scale, things like amber and oysters which require carbon based life are infinitely more valuable or rare than diamonds or something that doesn't require life.

The value judgment on that is so skewed, it’s culturally informed more than related to the actual conditions of its existence.

Yeah. On a cruise ship, the most expensive rooms are at the top, but because it's a boat, you can't use really heavy materials at the top of a boat, so it's inverted. It's like marble versus laminate; things that are heavier are perceived as more valuable. It's an example of where things get messed up in an interesting way, and I feel like that's Ficus-coded.

Is there a close relationship between the materials that you use and the content or subject matter of the work? There's the bar piece where you have the peanuts [Los Angeles Bar Top, 2024], which is a more direct connection versus—I noticed the selenite that you have on the table—a spiritual or metaphysical association with what's in the work and what the work represents or is getting at conceptually.

I don't think so, because terrazzo is such a haphazard process. We have a collection of wish bones that our friend Max gave to us, and we haven't used them yet because we're scared they’ll get lost in the mix, literally. I think if we had more control over the process, then we could use materials that had value in that way. This [referring to the selenite] was some random thing I got, but it's going to become a candle like in this drawing [referring to a sketch of a birthday cake], but we didn't think of this and then ask “what should the candle be?”

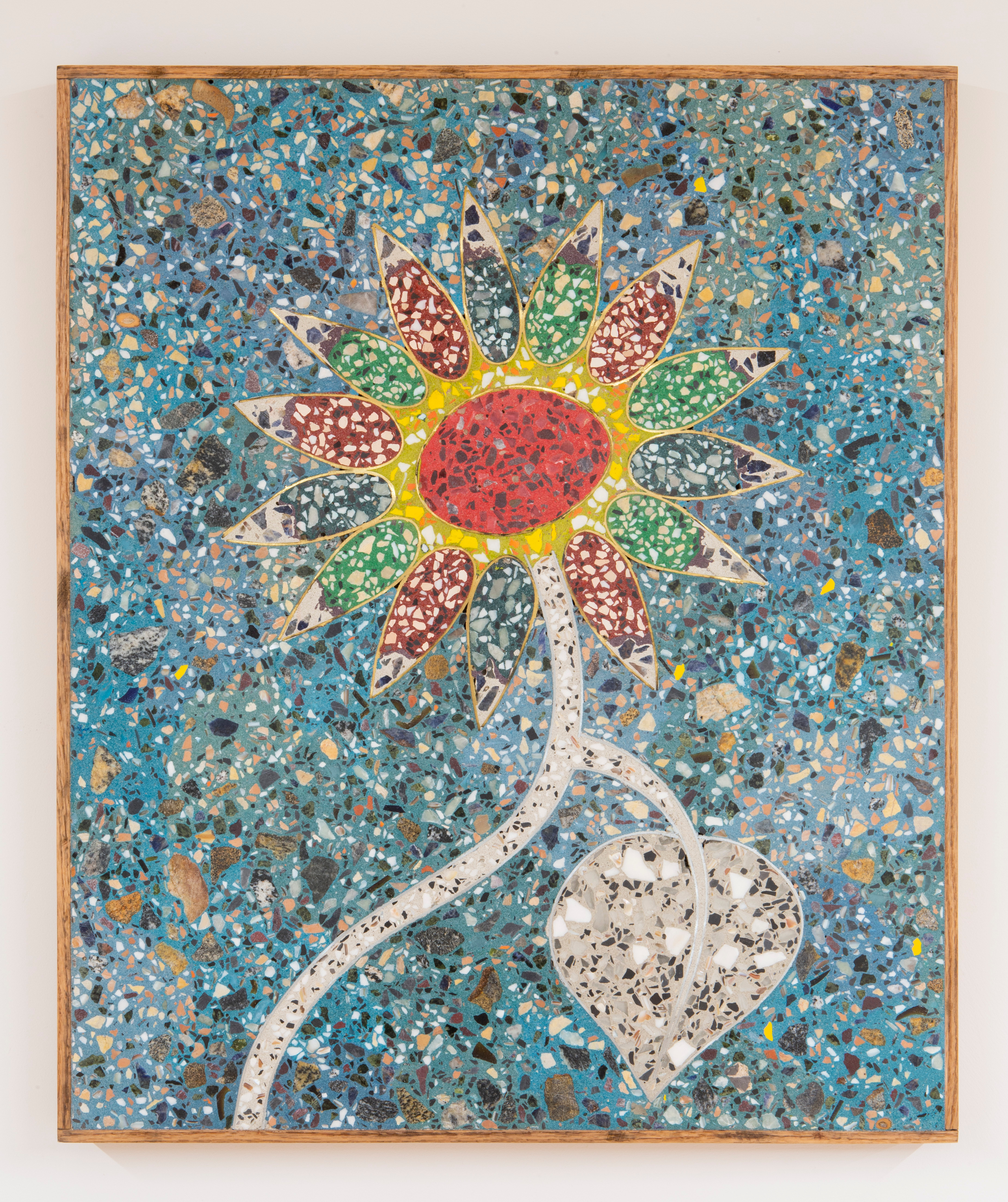

I would say 90% of the time it's more about a formal choice than a deeper meaning. But there are times, especially with commissioned works, where we’ll tell people if you have a sentimental collection of rocks or shells we can find a way to fit those in. And I also think about the sunflower pieces that we've done. We made one for my mom, and every petal had a different sort of material meaning. There was coral from Puerto Rico and rocks from upstate, and corn kernels that my childhood friend had grown in her garden. I think there are certain times where we try to zero in on that more than other times. Part of it is that the rocks are plentiful, so it's hard to make them all have a really specific meaning or value. It's more about creating that visual field that makes a bigger image. But when there's an opportunity to, I think it's a nice thing to do.

I think it's about legibility too. Because if a client says “can you please put in this precious rock from my honeymoon” or whatever, we’ll say sure, but we don't have control over what part of that rock is going to poke out through the terrazzo. So as long as they’re okay with that legibility. The wishbones, for example, are such a precarious thing because we have one millimeter of error. If you grind it too long, then it's just gone.

I would say 90% of the time it's more about a formal choice than a deeper meaning. But there are times, especially with commissioned works, where we’ll tell people if you have a sentimental collection of rocks or shells we can find a way to fit those in. And I also think about the sunflower pieces that we've done. We made one for my mom, and every petal had a different sort of material meaning. There was coral from Puerto Rico and rocks from upstate, and corn kernels that my childhood friend had grown in her garden. I think there are certain times where we try to zero in on that more than other times. Part of it is that the rocks are plentiful, so it's hard to make them all have a really specific meaning or value. It's more about creating that visual field that makes a bigger image. But when there's an opportunity to, I think it's a nice thing to do.

I think it's about legibility too. Because if a client says “can you please put in this precious rock from my honeymoon” or whatever, we’ll say sure, but we don't have control over what part of that rock is going to poke out through the terrazzo. So as long as they’re okay with that legibility. The wishbones, for example, are such a precarious thing because we have one millimeter of error. If you grind it too long, then it's just gone.

Los Angeles Bar Top, 2024,

cementious terrazzo, 18 x 90 x 1.5 inches

courtesy of the artists

What do you find is the conceptual thread, rather than formal or material, that links the tables and the paintings?

The ideas for the tables and the wall works come from the same place. But, I don't know, my dream when I die would be to create multiple ways for someone to ask “is that Ficus Interfaith?” whether it's a floor or a painting or whatever. In the same way that something in a museum is attributed to a culture, and it speaks to that culture versus someone's unique vision.

I don't think there's a specific conceptual thread, and maybe on purpose. Certain artists work in a really defined way, where they're trying to achieve a goal for the viewer to recognize. I think we've really purposefully tried to make it feel like throwing darts at a world map. I don't know if it's visual, exactly, but there's an ethos. There's something at the core of everything that kind of makes it recognizable as a Ficus Interfaith, and it's not necessarily that it's terrazzo.

We have a new body of work that is not terrazzo planned for next year, but, even in that body of work, the patterns that emerge are from a deep research into material and history and a relationship with time and decoration, as well as fine art. When I walk through a museum, it's easier for me to connect to an ancient time when there’s an object that you can use, because it's a lot easier to imagine using it. Whereas a painting of someone is an edited idea versus something that they used or wore. I think as we continue to grow our practice, it’s fun to be like, “how would Ficus make this?” in the same way that we do that with terrazzo, you know, whether it's a different method or material.

I don't think there's a specific conceptual thread, and maybe on purpose. Certain artists work in a really defined way, where they're trying to achieve a goal for the viewer to recognize. I think we've really purposefully tried to make it feel like throwing darts at a world map. I don't know if it's visual, exactly, but there's an ethos. There's something at the core of everything that kind of makes it recognizable as a Ficus Interfaith, and it's not necessarily that it's terrazzo.

We have a new body of work that is not terrazzo planned for next year, but, even in that body of work, the patterns that emerge are from a deep research into material and history and a relationship with time and decoration, as well as fine art. When I walk through a museum, it's easier for me to connect to an ancient time when there’s an object that you can use, because it's a lot easier to imagine using it. Whereas a painting of someone is an edited idea versus something that they used or wore. I think as we continue to grow our practice, it’s fun to be like, “how would Ficus make this?” in the same way that we do that with terrazzo, you know, whether it's a different method or material.

My dream when I die would be to create multiple ways for someone to ask “is that Ficus Interfaith?” ...

in the same way that something in a museum is attributed to a culture, and it speaks to that culture versus someone's unique vision.”

It’s interesting to hear you also talk about Ficus as if it is this third person in the room. Do you see it as separate from either of yourselves, or does it feel more like it's just the two of you in a partnership?

I think it's a third thing. We have to put on our Ficus goggles and make the art that way, versus, like if one of us had this fully baked idea about say, whales in the Indian Ocean that just has nothing to do with the other. But if we can stop before that and say “this is what is interesting to me, what do you think about this?” then it can move through the next stage.

I think it's definitely become a third entity, because there are things that I’m interested in, there are things that Ryan is interested in, and then there's things that Ficus Interfaith is interested in, and it's an ever shifting Venn diagram. Now, we're well versed enough that we can kind of feel it in our brains when we come across an idea that makes sense for the Ficus Interfaith practice.

And it’s not in a way that's a brand or a persona. If you think about a performer, it's a very common strategy to create a character as a creative exercise. And then it’s about “what would your alter ego do?” I think all of these works are still very personal, but it's just not about our individual lives.

I think it's definitely become a third entity, because there are things that I’m interested in, there are things that Ryan is interested in, and then there's things that Ficus Interfaith is interested in, and it's an ever shifting Venn diagram. Now, we're well versed enough that we can kind of feel it in our brains when we come across an idea that makes sense for the Ficus Interfaith practice.

And it’s not in a way that's a brand or a persona. If you think about a performer, it's a very common strategy to create a character as a creative exercise. And then it’s about “what would your alter ego do?” I think all of these works are still very personal, but it's just not about our individual lives.

I forget how we started that, but the rule was that there are no rules and we're never going to talk about it. So it just turned into what it is, one of us would post, and then someone would respond, or someone wouldn't, and then it became this collaborative exercise.

It was also a way to leave notes for each other. Now we just see each other every freaking day, so there's no need for that. It was a way to have a website that didn't function as just a portfolio. I think there's times with artist websites where it's just a portfolio of the work, which isn't so fun to click through. So ours is more of a blog format where there's inspiration and poetry, things you find, things you write, and then also documentation of the work. The primary function was to have fun and to show each other cool stuff, which, at the end of the day, that's what Ficus is still.

It was also a way to leave notes for each other. Now we just see each other every freaking day, so there's no need for that. It was a way to have a website that didn't function as just a portfolio. I think there's times with artist websites where it's just a portfolio of the work, which isn't so fun to click through. So ours is more of a blog format where there's inspiration and poetry, things you find, things you write, and then also documentation of the work. The primary function was to have fun and to show each other cool stuff, which, at the end of the day, that's what Ficus is still.

It’s also nice, because there's a lot of content on there that isn’t available anywhere else. If you go far down your CV, there are exhibitions that you can't find anywhere else online. There’s a lot of poetry and a lot of research, but is any of the writing on the blog your writing? There are a couple of posts where I noticed you didn’t cite an author.

Yeah, there is. One of the first things we ever did was write poetry together, which is probably the hardest thing we've ever done. You can draw with someone, whether you're holding the pen together or making an exquisite corpse. But to write a poem with someone… I don't know how songwriters do it. Yeah, we wrote poems together, but we haven't in a long time.

It is really challenging to write together, especially in the poetry form, because everything is essentialized, you're trying to get to this essential part of every word, and there’s a different meaning for everybody.

It is really challenging to write together, especially in the poetry form, because everything is essentialized, you're trying to get to this essential part of every word, and there’s a different meaning for everybody.

“A symbol functions as a way to communicate something, but beyond that, if you don't speak the language, then the visual form is all you're left with.”

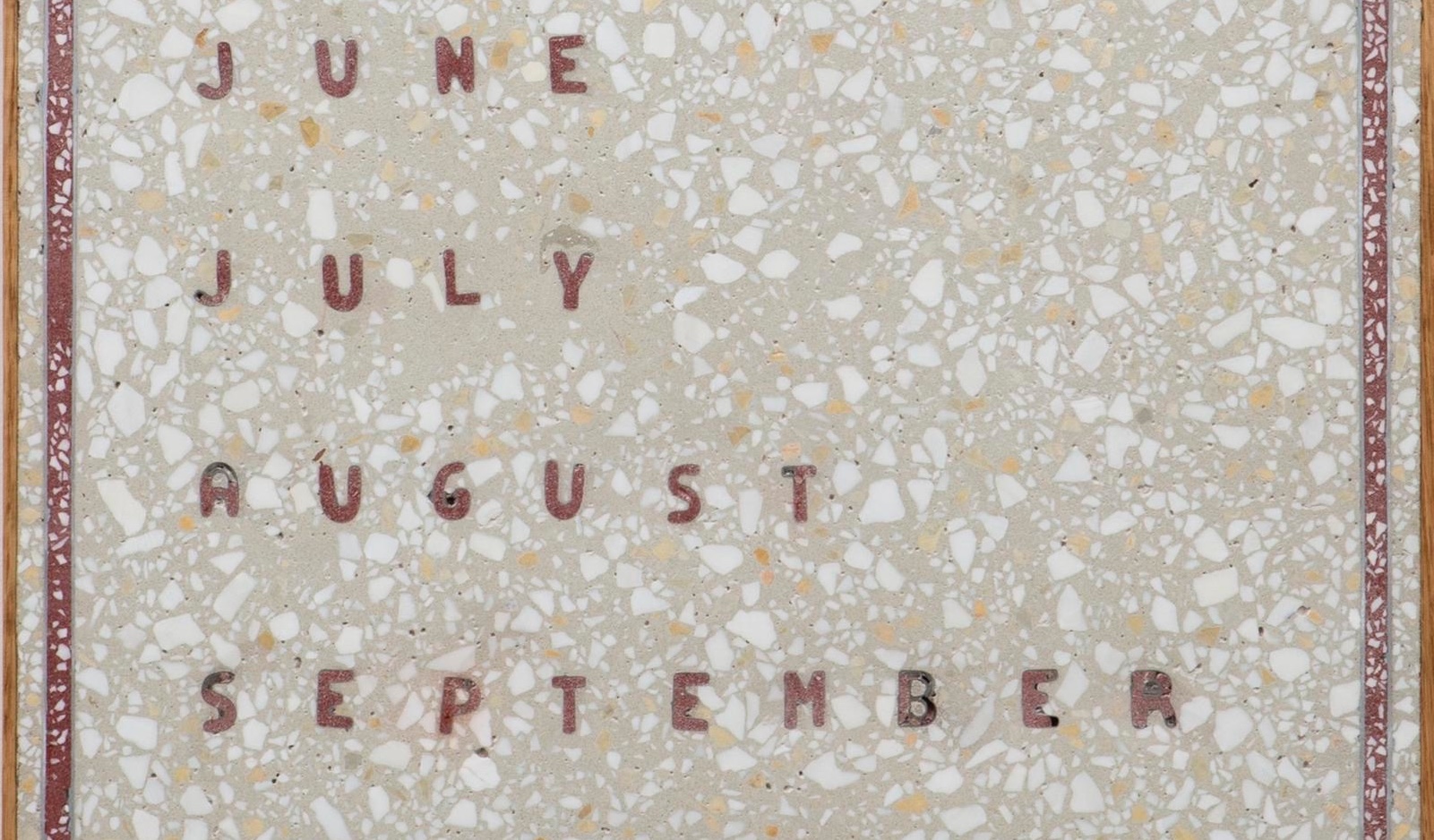

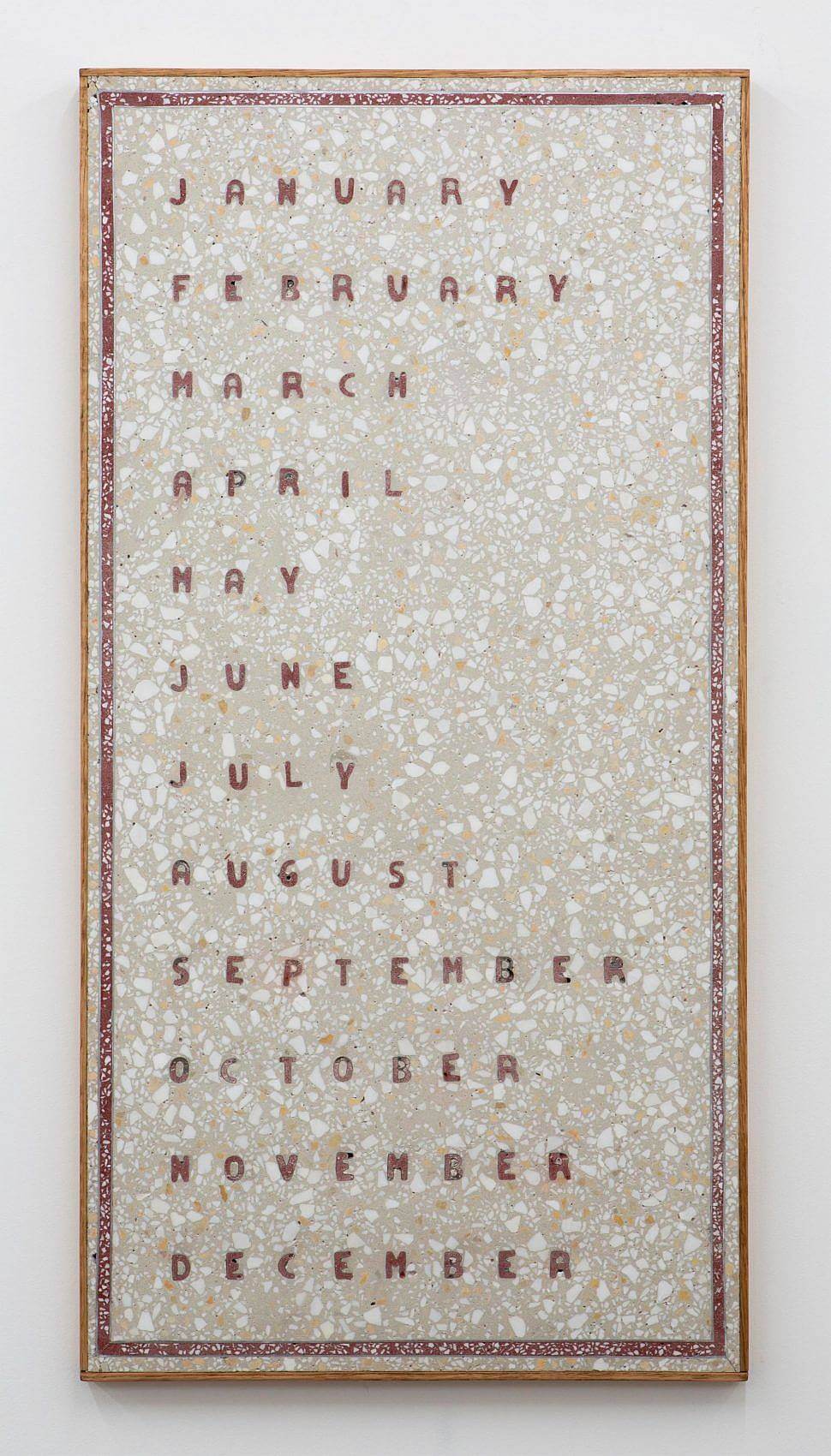

You have a work that's a vertical list of the months [Calendar Sign, 2021]. For you, does that work function merely as a representation of the words themselves? And how might that be different from the function of a representation of a flower or a figure.

We use text quite a lot in our work. Sometimes they operate as poems, but more often it's Ed Ruscha-ish, where the word is a visual and emotional idea in itself. We had a piece that just says “MENU” [2024] or we had a text piece that just said “MATERNITY” [2022]. While we were doing that, we were asking what rocks would make sense with this in the same way that having the word maternity in a certain font, in a certain color can mean certain things. We chose pink and white and mother of pearl… But then sometimes we write poems, and they’re written in the terrazzo.

The words that we end up using have either a lot of different interpretations possible, or it took a long time to get to the standard interpretation of it. For the calendar piece [Calendar Sign, 2021], I remember doing research about all the different calendars that people have used throughout history and different cultures. It’s this heap of information that ends with what we use now. Behind the pretty obvious and simple list of months is all this built up usage and culture that we kind of take for granted. The idea is to represent that and let it vibrate.

A word as a symbol is a really interesting idea. Kind of like what Jasper John says through signs and symbols. A symbol functions as a way to communicate something, but beyond that, if you don't speak the language, then the visual form is all you're left with. Those are ideas we think of with the word pieces, like an exit sign: if it's above a door, then it's a real exit sign, but just a few inches over or on the opposite wall, everything changes.

The words that we end up using have either a lot of different interpretations possible, or it took a long time to get to the standard interpretation of it. For the calendar piece [Calendar Sign, 2021], I remember doing research about all the different calendars that people have used throughout history and different cultures. It’s this heap of information that ends with what we use now. Behind the pretty obvious and simple list of months is all this built up usage and culture that we kind of take for granted. The idea is to represent that and let it vibrate.

A word as a symbol is a really interesting idea. Kind of like what Jasper John says through signs and symbols. A symbol functions as a way to communicate something, but beyond that, if you don't speak the language, then the visual form is all you're left with. Those are ideas we think of with the word pieces, like an exit sign: if it's above a door, then it's a real exit sign, but just a few inches over or on the opposite wall, everything changes.

![]()

![]()

Calendar Sign, 2023

cementious terrazzo in oak frame, 48.75 × 24.75 × 1.25 inches

Courtesy of The Valley

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Installation view, Wysteriasway, 2016,

Proxy, New York, NY

Those ferrocement stacked swans [Ferrocement Bird Pole, 2017] were a recurrent theme a few years ago, can you talk about those works?

With those works, we let the availability steer the direction. We didn't really set out to make those swans. It emerged through what was available at thrift stores, leaning into that randomness, which then becomes super intentional. If there were a bunch of other animals, then that's just what it would have been. That whole project was based on this website that we stumbled across where this guy was making reinforced cement structures with natural fiber material, like bamboo and reed and wicker. His project was for places that don't have a lot of access to construction material, like in order to build permanent structures pretty quickly if a hurricane is coming or you need to store something and you don't have access to a Home Depot.

So we took that idea of ferrocement, or reinforced cement with natural materials, and thought the abundance of wicker and rattan furniture that's in Salvation Army’s could be the basis for this type of sculptural work that uses what's at hand. And those bird baskets were Avon giveaways or something. They would put the products in these little swans and doves. But again, it's leaning into what's available, versus “let me meditate and clear my mind and whatever enters my mind is what I make.” It's embracing this post consumerism ideology. It's intentional, and we edit it, but yeah, we love birds, so it was perfect in that way.

We just went out looking for wicker objects, and you recognize that these birds are at every store. People are donating them, or throwing them out everywhere, so they're cheap and available, and almost over abundant and so creating a sculpture of that repetition of them became the impulse. There were other things that there were a lot of as well that weren’t as aesthetically striking to us, that we didn't use.

So we took that idea of ferrocement, or reinforced cement with natural materials, and thought the abundance of wicker and rattan furniture that's in Salvation Army’s could be the basis for this type of sculptural work that uses what's at hand. And those bird baskets were Avon giveaways or something. They would put the products in these little swans and doves. But again, it's leaning into what's available, versus “let me meditate and clear my mind and whatever enters my mind is what I make.” It's embracing this post consumerism ideology. It's intentional, and we edit it, but yeah, we love birds, so it was perfect in that way.

We just went out looking for wicker objects, and you recognize that these birds are at every store. People are donating them, or throwing them out everywhere, so they're cheap and available, and almost over abundant and so creating a sculpture of that repetition of them became the impulse. There were other things that there were a lot of as well that weren’t as aesthetically striking to us, that we didn't use.

I'm imagining Staten Island or New Jersey commissioning you guys to clear out the junk yards for whatever in one big recycling project.

We're working on a project for this shop in Chinatown called Wing on Wo. They sell porcelain ceramics, and we're using the broken porcelain as the aggregate. So that's an example of using whatever they have to determine the size and the shapes of all the little rocks. Instead of us setting out to make porcelain terrazzo, this is more fun.

Exit Sign, 2024,

cementious terrazzo, 10 x 14 x 1.5 inches

Courtesy of the artists

In the blog a lot of the poems felt spiritual, sometimes overtly, like the Flannery O'Connor diary entries where she was writing down prayers to God. I'm wondering if the project is in some way religious or devotional.

It's a complicated thing. We're two different people, and neither of us are religious. Raph is Jewish and my mom grew up Catholic and rejected it, so I'm the product of her rejection. Basically I was raised atheist or agnostic I guess. Interfaith started as a way for us to examine the idea that's connected to faith in God, but in more of a narrative art kind of way. And also faith as something connected to the idea of hope, where if you have faith in yourself or in your peers or in the world. That tone is something that we seek to embody with Ficus Interfaith. It invites this grander idea of humans as a small part of a bigger thing.

I think this is something similar to what we were talking about with the calendar piece. It's this pyramid of knowledge, where the tip is where we are now, but there's all these different versions of what people have practiced or thought or felt spiritual about that informs the next generation, the next, and the next. When you read about people's thoughts and beliefs about faith and religion, you just accept that you understand what they're talking about. We are all kind of brought up in these different modes, or exposed to different modes of thinking about that. I do think there is an opportunity to look at it as a shared human experience, even if I don't really feel particularly spiritual or religious myself.

The connection between art and religion is the biggest, oldest thing ever. For thousands of years, if you were an artist, you worked for the church, and there's still so many remnants of that. We are infinitely fascinated by that, like the way the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul has gone from a church to a mosque. Within Christianity, it's very common to illustrate God as a human, but that's forbidden in Islam, so they covered up all the images of people, and only calligraphy is allowed. The Reformation did something similar. I also think creativity is itself a kind of spiritual act—and you have to believe in something.

What you're talking about in Islam is what contributes to all of this amazing pattern work and crafts that use incredible patterns from abstracting icons and language and writing to the point where it's acceptable in those holy spaces. I remember going to Alhambra in Spain, which is this massive complex, and, when you walk through, it starts with more recognizable imagery, and as you move towards the center, it gets abstracted, abstracted, abstracted, until you have what are essentially these incredible math equations through pattern that started as letters and script. So it is really interesting how religion seeps into all these different aspects of visual life, without necessarily being obvious.

I think this is something similar to what we were talking about with the calendar piece. It's this pyramid of knowledge, where the tip is where we are now, but there's all these different versions of what people have practiced or thought or felt spiritual about that informs the next generation, the next, and the next. When you read about people's thoughts and beliefs about faith and religion, you just accept that you understand what they're talking about. We are all kind of brought up in these different modes, or exposed to different modes of thinking about that. I do think there is an opportunity to look at it as a shared human experience, even if I don't really feel particularly spiritual or religious myself.

The connection between art and religion is the biggest, oldest thing ever. For thousands of years, if you were an artist, you worked for the church, and there's still so many remnants of that. We are infinitely fascinated by that, like the way the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul has gone from a church to a mosque. Within Christianity, it's very common to illustrate God as a human, but that's forbidden in Islam, so they covered up all the images of people, and only calligraphy is allowed. The Reformation did something similar. I also think creativity is itself a kind of spiritual act—and you have to believe in something.

What you're talking about in Islam is what contributes to all of this amazing pattern work and crafts that use incredible patterns from abstracting icons and language and writing to the point where it's acceptable in those holy spaces. I remember going to Alhambra in Spain, which is this massive complex, and, when you walk through, it starts with more recognizable imagery, and as you move towards the center, it gets abstracted, abstracted, abstracted, until you have what are essentially these incredible math equations through pattern that started as letters and script. So it is really interesting how religion seeps into all these different aspects of visual life, without necessarily being obvious.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Installation view, Ficus Interfaith, 2019,

Jack Chiles, New York, NY

The sunflower seems to occupy a very central space in your practice too. It feels very joyful and full of hope or faith, because it has this symbolism of rising towards the sun. And then you have the Allen Ginsberg poem in one of your shows that you referenced.

When we were doing that show [Ficus Interfaith, Jack Chiles, 2019], one of the things we came across was that the sunflower is a remediation plant. They have been planted to help clean up radiation from nuclear disasters, including Chernobyl and Fukushima. We realized there's a nice analogy there with the terrazzo, the materiality of the terrazzo being made up of post consumer goods, or recycled goods turned into something beautiful. There's an obvious analogy to that as a symbol. But apart from that, it’s super recognizable.

We also consciously chose it as a template. We've made probably 15 in that exact way. When we make gifts for people, it's become “oh, let's make them a sunflower.” We change certain things. That one [referring to a work in the studio] is the bar version, where it has the peanuts, and then all of the petals and the background essentially serve as a legend for all of the other terrazzo works in the show. When we have extra concrete, we just put it in the sunflower. The bar top itself became the background with all those wood chips. For our next show, we’ll make a sunflower, and then it'll be a remediation plant for the process. Like Raph said, he made one for his mom. A few years ago, we each made one and as a creative exercise hid the process from each other. So we made all of the creative decisions alone. And then we had a reveal, like “what does yours look like?” So in our apartments, we have our individual Ryan sunflower and Raph sunflower. In that way, it's a vehicle for experimentation as well.

We also consciously chose it as a template. We've made probably 15 in that exact way. When we make gifts for people, it's become “oh, let's make them a sunflower.” We change certain things. That one [referring to a work in the studio] is the bar version, where it has the peanuts, and then all of the petals and the background essentially serve as a legend for all of the other terrazzo works in the show. When we have extra concrete, we just put it in the sunflower. The bar top itself became the background with all those wood chips. For our next show, we’ll make a sunflower, and then it'll be a remediation plant for the process. Like Raph said, he made one for his mom. A few years ago, we each made one and as a creative exercise hid the process from each other. So we made all of the creative decisions alone. And then we had a reveal, like “what does yours look like?” So in our apartments, we have our individual Ryan sunflower and Raph sunflower. In that way, it's a vehicle for experimentation as well.

above: Raphael Sunflower, 2021,

cementious terrazzo, 24 x 20 x 1.25 inches

below: Ryan Sunflower, 2021,

cementious terrazzo, 24 x 20 x 1.25 inches

Courtesy of the artists

Ficus Interfaith is a collaboration between Ryan Bush (b. 1990, Colorado) and Raphael Martinez Cohen (b. 1989, New York City). As a sculptural practice, Ficus Interfaith pursues projects that investigate ingenuity and novelty as it emerges from craft. Their research focuses on historical imagery, language, and symbolism that is ubiquitous to the point of being overlooked or misunderstood. Using terrazzo, a composite material consisting of leftover marble, glass, and other waste used to make decorative floors since antiquity, Ficus Interfaith embraces the spirit of collaboration and reuse while reimagining how craft can enter our lives and affect the spaces we create and inhabit.

︎: @ficusinterfaith