Maya Yadid

Through sculpture, installation, and video works, Maya Yadid’s (b.1986, Jerusalem) multifaceted practice evokes complex shared histories. Yadid’s recent bodies of work utilize the symbolically laden materials of clay, food, and household objects in clever, restrained language.

We discuss her fraught and personal relationship with the history of food, social relations in her native region, and the value of work that’s not meant to last.

Do you have a rose and thorn for the past week?

We discuss her fraught and personal relationship with the history of food, social relations in her native region, and the value of work that’s not meant to last.

Do you have a rose and thorn for the past week?

You mean the best thing that happened to me and the worst thing that happened to me? Oh my god. A friend of mine who's a Jewish-French curator wanted to start selling judaica that is made by contemporary artists. She invited me to make these ceramic menorahs for Hanukkah, which I did. I also just finished a show, so I was happy to make something that is more crafty and work with my hands. I made five and they all sold out in a week. So yeah, that was a really nice treat. And then I suppose my thorn is that I left my studio at Hunter after three years. I'm happy to spread my wings, but it's definitely sad.

Did you graduate in the spring semester?

I was supposed to graduate in the spring, but our show got postponed. So it was in October.

Did you graduate in the spring semester?

I was supposed to graduate in the spring, but our show got postponed. So it was in October.

![]()

Installation view, What is Hidden, 2019,

Hunter College, New York, NY

When was the physical show? Was it coordinated at the same time as the online show?

Actually the Hauser & Wirth online exhibition was a couple weeks after our physical show ended.

How did you feel about the show? Was it still exciting, all things considered?

It was a very exciting two weeks. I feel like COVID actually had a weird effect in a positive way. At first, we were bummed because we couldn't have a big opening, and there was the whole complicated bureaucracy of setting appointments for visitors through CUNY. We were kind of nervous, but a lot of people came and it was exciting to see everyone after months and months. It was such a precious moment just to be there, and to have a show. I work with sculpture, so I was really worried about having an online show, I also had to completely change my plan for the show, because the original plan was irrelevant due to Covid. So I ended up making this show in two months and it was great.

![]()

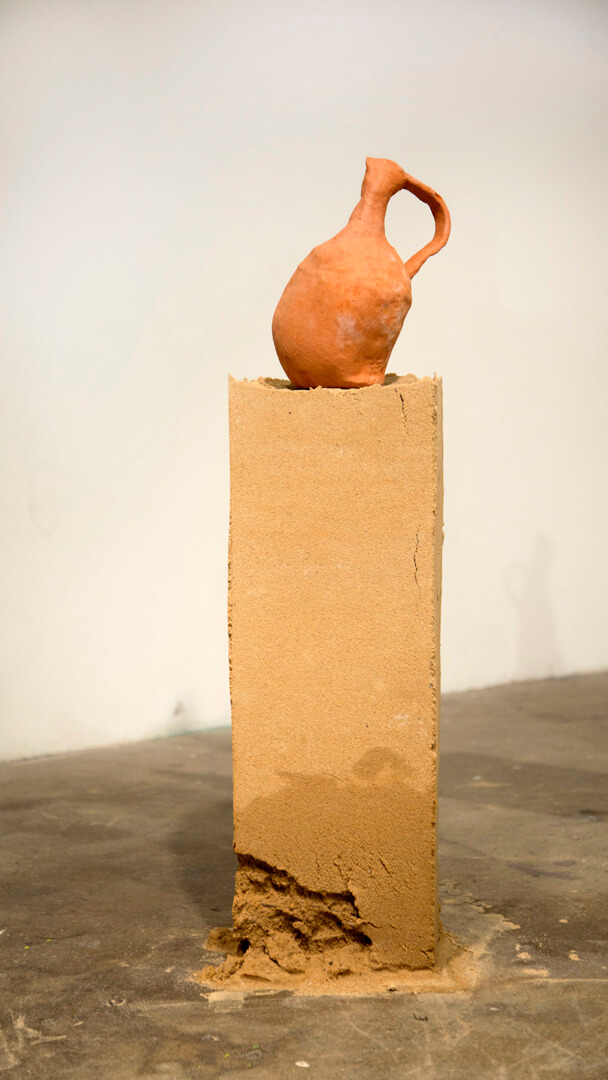

We Must Build as if the Sand Were Stone, 2019,

sand, mesh, unglazed ceramic vessels

Do you cook the bread inside of the ceramic vessel after you've already fired it?

Yes. That's something that happened in those two months, around the new date of the show. I was making the vessels, and I made the openings, and then I fired at a high temperature, which is called bisque firing. Then I took the vessels out of the kiln, made the dough, put the dough inside, and put it back in the kiln on a lower temperature. So It bakes inside the vessel, and during the bake just wants to burst out.

Did the popularity of baking bread during quarantine inspire those works?

I was already working with food, thinking about food. I was baking a little bit before COVID, but never dove into it. Then, while quarantining, there was more time to work with dough. I wasn't in the studio, so I wasn't working with clay, but then I realized that they have a lot of things in common.

Do you worry about the conservation of these pieces?

I have a tendency to make things that can't last. I think it's my way of staying out of the market world. I know that people buy everything, so it doesn't necessarily mean that there's no place for it in the market, but I wasn't thinking about that when I made them.

The conservation issue was brought up a lot during the show, because I think people are bothered by the idea that this thing is not going to last forever. I think the concept of art that lasts forever is something that we are taught to think of as built in.

But eventually I had to make it, and told myself, “I'll see what happens.”

There is actually bread from ancient Egypt in the Metropolitan Museum. And there's also the Salvador Dali at the MoMA. Those works can be preserved for a long time if there's no humidity. If it's dry enough, there's no moisture, there's no bacteria–then it's fine. Museums have ways to preserve these pieces, and I didn't. I put them back in the kiln on a very low temperature for hours, trying to get them bone dry and then kept them all in my studio just to see what happened. It was nasty though.

The conservation issue was brought up a lot during the show, because I think people are bothered by the idea that this thing is not going to last forever. I think the concept of art that lasts forever is something that we are taught to think of as built in.

But eventually I had to make it, and told myself, “I'll see what happens.”

There is actually bread from ancient Egypt in the Metropolitan Museum. And there's also the Salvador Dali at the MoMA. Those works can be preserved for a long time if there's no humidity. If it's dry enough, there's no moisture, there's no bacteria–then it's fine. Museums have ways to preserve these pieces, and I didn't. I put them back in the kiln on a very low temperature for hours, trying to get them bone dry and then kept them all in my studio just to see what happened. It was nasty though.

![]()

Cloudy Vessel, 2020,

ceramic, bread, fabric, kitchen cabinets

Let’s lead into the archival works. You have that work The Archivist’s forgetfulness (2020) and I was wondering what the archive means for you? The concept of the archive is being pretty heavily interrogated right now, but it feels like you took a very sympathetic approach to it.

That's interesting. I haven't thought about it as a sympathetic approach. My approach comes from growing up surrounded by a very, very strong narrative that doesn't belong to me. I started learning about it around undergrad, realizing there's a whole other narrative that I need to insist on learning from my history. And that made me dig into archives, and learn through photography. This series came from photographs that I don't represent in a very cohesive way. I meshed them together in a way that was almost wrong. I found images that were taken in different places in the world, within different contexts but in the same year, and I made a collage with them. I wanted to do this in a way that messes up the archive, you know?

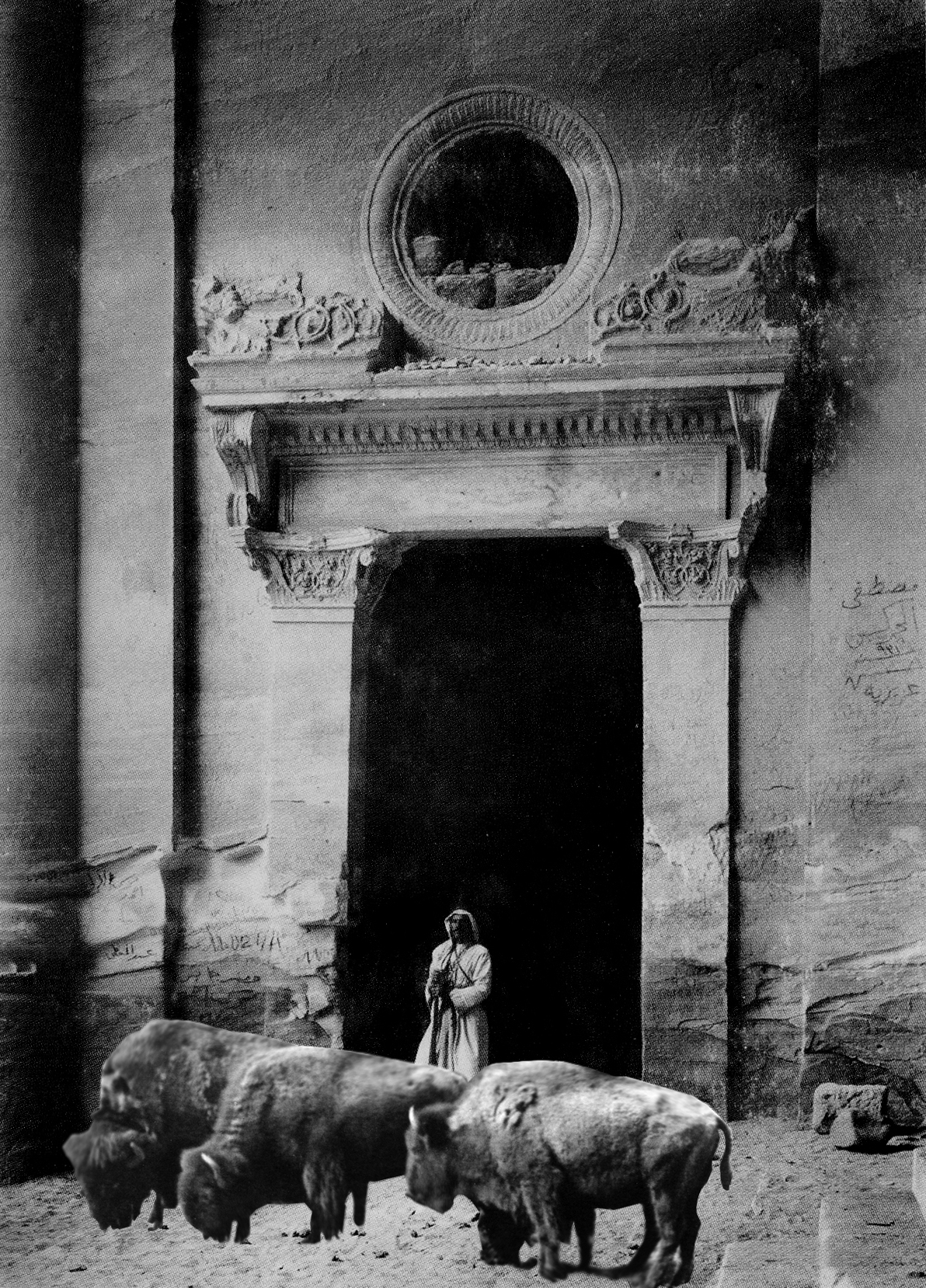

![]()

The Archivist’s Forgetfulness (series), 2020,

digitally collaged archival images

They seem like they trick the eye, because the collage aspect is so subtle.

The way I was making the cuts was actually pretty rough. I wasn't trying to make the cuts precise, but because it's black and white, it kind of tricks you, it's true. If you look closely, there's moments where you can see where it's being cut.

Those were my friends, they were a couple at a time. We hung out a lot, and I'd seen a lot of the shows that they were doing. So I knew the qualities that they have. I don't want to say that I was building these characters for them, because that's not exactly true. But in the back of my mind, it was clear to me that it was the two of them.

I was really interested in all of the little mannerisms that they have, which felt very intentional, but, at the same time, were really minor details that added a lot to the emotional tone. What was the intention behind those details, like chewing gum or smoking cigarettes?

They were a bit of a caricature. I wanted to reference American cinema in the back of my mind, things like Wild at Heart (1990), and that sort of aesthetic, very John Travolta. But I was thinking about it in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the privilege of some Israelis to appropriate that sort of dream, or use that sort of aesthetics in general. So I combined these American and Israeli type casts. I wanted to reference American cinema in that sense, because I wanted to talk about the effect of Western culture in that conflict.

![]()

433, 2010,

video

In America, the idea of the open road is so loaded, there’s an entire genre of literature, film, etc. about it. Then you put these characters on that specific road which is also loaded.

I was definitely thinking about the idea of the open road that exists a lot in American cinema, and that specific road is completely the opposite. It's a road that connects Jerusalem to the largest settlement in the area, which is called Modi’in. It's a huge settlement. It's not an ideological settlement, but it still is a settlement and it sits in the middle of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv and between Palestinian villages. The separation wall was built along that road, sometimes splitting palestinian villages into halfs, you can see it in the video. That road is extremely problematic, for many years Palestinians were banned from driving on it, and basically were forced to drive on smaller roads so instead of driving half an hour to their village, they would have to circle around for much longer. There was a lot of violence around that road and that was something that I wanted to reflect on. I thought the idea of the open road was kind of ridiculous, considering all of these aspects.

![]()

433, 2010,

video

Could you talk a little bit about the cleaning lady (2012)? It feels like it has some distinct connections to American cinema. But it also feels very specific.

That's actually me in the video. When I was making all these videos, I was thinking a lot about appropriation. I specifically wanted to recreate a situation that I actually saw for myself. I was in an airport in Istanbul, and I went into the bathroom and saw a cleaning person basically leaning on the hand dryer, warming her back.

I felt trapped in that moment, and it stayed with me for a long time. And for a while, I thought “Who should I cast for it?” I ended up putting myself there because eventually it was me who connected with that moment on a weird level. I felt like I needed to be there in the bathroom and do it.

As opposed to 443 or Forbidden Love (2010), where I had a full script and production, I didn't really know what it was going to end up being, I just wanted to make it. I was editing it for a while, and then somehow brought in the music, it brought this level of nostalgia and in those years I was feeling nostalgic toward something that I didn't really know what it was.

I felt trapped in that moment, and it stayed with me for a long time. And for a while, I thought “Who should I cast for it?” I ended up putting myself there because eventually it was me who connected with that moment on a weird level. I felt like I needed to be there in the bathroom and do it.

As opposed to 443 or Forbidden Love (2010), where I had a full script and production, I didn't really know what it was going to end up being, I just wanted to make it. I was editing it for a while, and then somehow brought in the music, it brought this level of nostalgia and in those years I was feeling nostalgic toward something that I didn't really know what it was.

![]()

The Cleaning Lady, 2012,

video

Why did you end up moving away from video, was it a conscious choice?

It wasn't a conscious thing. I was making a little bit of video when I was in New York, before I started at Hunter. I was always making sculptures, but I was really bad at documenting my work so I don't have a lot of documentation of my early sculptures. Some of these videos attracted a lot of attention, and then people marked me as a video artist, which really bothered me because I wanted to push on other mediums too. But do I feel like video and sculpture are so connected. When I was making videos, I really wanted to create an environment or a world and I want to do that with sculpture, too.

![]()

![]()

Nekavim, 2020,

ceramic, bread, kitchen cabinet

Speaking of environment, what is the significance of the curtains in your installations?

It was mostly about “How do I make spaces? How do I build spaces? How do I fabricate architecture without having a little fortune in my bank account?” With the curtains, I was able to create rooms. The other reason is that I really like the psychology of passing through a curtain. What does it do to you when you pass through a curtain? I feel that it brings you into something. You take that step and there’s a kind of dreaminess, or surrealist reference. It also brings softness into the space.

I like the idea of having a backroom and I was able to do that with the curtains. The idea of being behind the stage or behind the scenes, I'm pretty fascinated by it.

It’s also a way to manipulate the movements in the space. Maybe that's kind of going back to video making in a way. When you're editing, you decide what comes first and how you build up something. So in that sense, it's also like a way to build up.

I like the idea of having a backroom and I was able to do that with the curtains. The idea of being behind the stage or behind the scenes, I'm pretty fascinated by it.

It’s also a way to manipulate the movements in the space. Maybe that's kind of going back to video making in a way. When you're editing, you decide what comes first and how you build up something. So in that sense, it's also like a way to build up.

![]()

Installation view, What is Hidden, 2019,

Hunter College, New York, NY

What about food is inspiring to you?

I'm still figuring that out. I think food was always a big part of my life, because a lot of my family are cooks and work in restaurants, I grew up in it. For many years I didn't want anything to do with it, but it's part of my vocabulary. I'm also a food history nerd, and to go back to what we were talking about in terms of the archive and access to history–or access to other narratives–I realized at a certain point that food is a really interesting way to learn about other narratives. With many cultures, of course, but especially when you think about Arab-Jewish cultures. There's not a lot left in terms of writings but you can track down all sorts of things through food, and it's fascinating as a way for me to learn, which is something that I realized pretty recently. Why is it significant for me, why am I reading about this all the time? When you’ve immigrated to a different country, what's left is these memories that you're trying to make sense of, and they keep changing all the time. Food is loaded with memories, because food is often such an oral history. Your grandma told your mother how to cook it, but maybe never wrote down all the ingredients.

And in that sense, I really, really love the floor writer and researcher Claudia Roden. She left Egypt in the 50s, because the Jewish community was basically exiled. After leaving Egypt, she started collecting all these recipes from families and became an amazing pioneer of food history, not in the sense of writing a history book, but making a recipe collection which is a history book. She talks about how, before the community left, people wouldn't share recipes, because it has to do with family prestige and pride. But then people left and there was all this fear and uncertainty, and I think nostalgia too. People started sharing and exchanging recipes because they wanted to remember each other. So she talks about that change in her community.

And in that sense, I really, really love the floor writer and researcher Claudia Roden. She left Egypt in the 50s, because the Jewish community was basically exiled. After leaving Egypt, she started collecting all these recipes from families and became an amazing pioneer of food history, not in the sense of writing a history book, but making a recipe collection which is a history book. She talks about how, before the community left, people wouldn't share recipes, because it has to do with family prestige and pride. But then people left and there was all this fear and uncertainty, and I think nostalgia too. People started sharing and exchanging recipes because they wanted to remember each other. So she talks about that change in her community.

![]()

Bread Vessel #1, 2020,

ceramic, bread, marble tiles

Both food and clay are objects that are incredibly loaded with history and symbology. You're taking these two things and you're putting them together, and then you're also combining it all with kitchen cabinets. What’s the conversation between those three objects?

The clay and the bread are both ancient inventions that were very significant to humans and changed us, because it's the two reasons why we domesticated ourselves. We have to grow the wheat now, and dry it, and ground it. And then we have to take care of the clay and the fire pits to make all these pots. Then the pedestals are coming from a whole different time. I wanted to bring in some kind of comment on class, because I do think about class in relation to food, too. I was also trying to break the boring white pedestal kind of thing, I don't want to only show things on pedestals. How can that elevate the sculpture and how can it bring in another layer? At the same time, it’s also another container. I was thinking about working class kitchen cabinets. They're from Home Depot, basic working class cabinets.

![]()

Bread Vessel #3, 2020,

ceramic, bread, kitchen cabinet

My other question about pedestals concerns We Must Build As If Sand Were Stone (2019). How did you do that? There's so much tension between something that shouldn't be able to stay up like that and then, in turn, supports these vessels.

It came from a similar place. I started making these vessels and thinking about how to display them. I made the vessels in reference to the landscape that surrounded me when I was a kid in Northeast Jerusalem. From my house, on a good day, you could see the Judaean desert, Jericho, and at the very end, the Dead Sea. Across from us there was also a Palestinian village called Issaweia. It was a 20 minute walk–really, really close–but with no contact whatsoever. So I would wake up every morning to the muezzin, which feels like that was part of my culture too. So this really weird mashup of looking at these places that are part of my life, my everyday life, part of my culture, a part of my history, but also not. I was thinking a lot about this landscape. And these vessels are basically one of the first references for me for ceramics, because they were sold on the side of the road in those areas, which were made locally, and though they are almost touristic or decor today, they used to be used to carry water. They are made in the same traditions as these ancient vessels that we know from archaeological diggings.

So I felt like sand was the appropriate material to use. I was trying to figure out how to make a pedestal from sand. I did a lot of tests and ended up building them with water, and layers of mesh inside. They’re so strong, I could actually stand on it. It was an exciting moment, I was like, “Oh my god, I can build a house from sand.”

So I felt like sand was the appropriate material to use. I was trying to figure out how to make a pedestal from sand. I did a lot of tests and ended up building them with water, and layers of mesh inside. They’re so strong, I could actually stand on it. It was an exciting moment, I was like, “Oh my god, I can build a house from sand.”

![]()

Installation view, We Must Build as if the Sand Were Stone, 2019,

Hunter College, New York, NY

What about the title?

The title came later. My titles always come later. It's a quote by Jorge Luis Borges. Sand is fragile, clay is fragile, and ceramic is fragile, it all seems like it's gonna collapse. But it's actually really strong. It just brings in an emotional level.

The title relays a sense of community, with the use of “we.”

You're right, but I don’t know if I was necessarily thinking of community. I mean, community is always there. It's always a part because I think a lot about the social aspects in my work.

I feel like that is really clear in the bread cart. It’s a physical manifestation of an interaction between people that's based in food. Could you elaborate a little bit on how you came to that.

It started with my frustration about not being able to do what I was planning to do for this show. I really wanted to make a space where people can share food. I was starting to play with the clay and the bread together, and I was thinking about the food cart as this nomadic object that moves around. I was also affected by the last few months where I left my apartment in New York and left New York for a few months. I felt that even if I could make a space for sharing food, I didn’t want to, it just seems so insane with all of these restaurants closing.

So I was thinking about the food cart as this thing that moves around, but attracts gatherings of people . I think a food cart is in a way very local. If you go to another country and you eat in a food cart, you would eat something very local. So it has to do with locality. At the same time, in New York, it is run by immigrants. So it has this weird connection to locality and immigration that I was interested in. So I wanted to make a food card from something edible and was already working with bread at that point, but this time I needed to work with a bakery because I couldn't bake these big pieces in a home oven or a ceramic kiln. So I got in contact with a bakery in Brooklyn, called Caputo’s, in Fort Greene. They're a fourth generation Italian bakery. I made the whole thing from sculpture wire, and they wrapped it in dough and baked it in their big ovens. And then I used expanding foam to connect them together, which is funny, because expanding foam also acts like bread–it's excellent. I would want to do the piece one day where it's actually edible.

So I was thinking about the food cart as this thing that moves around, but attracts gatherings of people . I think a food cart is in a way very local. If you go to another country and you eat in a food cart, you would eat something very local. So it has to do with locality. At the same time, in New York, it is run by immigrants. So it has this weird connection to locality and immigration that I was interested in. So I wanted to make a food card from something edible and was already working with bread at that point, but this time I needed to work with a bakery because I couldn't bake these big pieces in a home oven or a ceramic kiln. So I got in contact with a bakery in Brooklyn, called Caputo’s, in Fort Greene. They're a fourth generation Italian bakery. I made the whole thing from sculpture wire, and they wrapped it in dough and baked it in their big ovens. And then I used expanding foam to connect them together, which is funny, because expanding foam also acts like bread–it's excellent. I would want to do the piece one day where it's actually edible.

![]()

Bread Cart, 2020,

wood, bread, foam, metal wheel

I've noticed that there's a recurring motif of fish in your work. Is that symbolic or personal?

So my dad had a fish restaurant when I was young, and that was the first place I worked. It was my summer job. It was the first moment where I felt like an adult. And so that's one little thing, but that made me think a lot about the reason why we eat fish, especially in Jerusalem, which is in the mountains. I was thinking about cultures that eat fish and reading about how fish is a symbol for luck in ancient Judaism. In Arab countries, there was a time where Muslims wouldn't eat fish, because it symbolized bad luck. So in that sense, a lot of the dishes in North Africa are originally from these Jewish communities. And there was also a certain point where these two symbols, the evil eye and the fish kind of mesh together. I started making these small fish vessels for a fish dinner party and after that I made the bigger version of them for the show. I feel like they have something to do with the other ceramic vessels in my work because they're mythological. At the same time they also kind of opposites, because the other vessels come from the ground and the fish come from the water. I just felt like this kind of dumb contrast is good for me.

![]()

Installation view, Under the Sea, 2020,

Hunter College, New York, NY

I noticed there's a video of you on Instagram breaking up a bunch of ceramics in Nari Ward’s class. Which I found interesting in regards to the fish as well, because there’s a can of Moroccan sardines on the table.

I had pieces of clay that were unfired, and they all had some food item in them. There was one with sardines, one with bread, one with these Egyptian cheese snacks, and then there was olive oil and zaatar, which is this herb mix. All of these things are very classic working-class foods. It has to do with sharing too, because you don't just eat a can of sardines by yourself. You open it and you put the cheese on the side, and you pour some olive oil with the zaatar and people share the bread. You eat a little bit of this and a little bit of that. I was thinking of that way of eating, and how these types of foods come from different places in the Middle East.

With the breaking, I wasn't sure how to keep the surprise effect but not have sensation of the breaking. When Clay is raw and unfired, it's dry. It's so fragile when you just tap it, it crumbles. So I ended up having this little hammer and people were actually breaking it. But I do think that if I make this piece again I won’t have a hammer. I would have something soft, because the act of breaking is not what's important, it's the act of revealing.

With the breaking, I wasn't sure how to keep the surprise effect but not have sensation of the breaking. When Clay is raw and unfired, it's dry. It's so fragile when you just tap it, it crumbles. So I ended up having this little hammer and people were actually breaking it. But I do think that if I make this piece again I won’t have a hammer. I would have something soft, because the act of breaking is not what's important, it's the act of revealing.

![]()

What is Hidden (detail), 2019,

table, fabric, broken unfired clay, homemade zaatar, olive oil, cheese

Visit Maya Yadid’s artist page.

︎: @mayayadid