Michael Stamm

Michael Stamm’s paintings blend emotive personal experience with witty societal critique. We spoke to the Brooklyn based artist about his current show at Shulamit Nazarian in Los Angeles, gay elders, and the “real” as it manifests in his carefully composed and often narrative-based body of work.

What is your rose and thorn for the week?

What is your rose and thorn for the week?

A rose for my week was getting to binge all of Search Party, a thorn for my week was having to paint again, having to start all over. I feel like after my show I have to redo all the things I did right but better, but I also have to do everything differently.

It's stressful, I have an opportunity coming up that I really want to do my best work for, so I'm immediately putting a lot of pressure on myself. I find it difficult to start new work because I want to do something new, and I want to have fun and do something that interests me, but I also want to build on what's been strong about the past work. It's hard to figure out what to retain or what to give up, particularly when you have external forces encouraging you to make a specific kind of painting.

It's stressful, I have an opportunity coming up that I really want to do my best work for, so I'm immediately putting a lot of pressure on myself. I find it difficult to start new work because I want to do something new, and I want to have fun and do something that interests me, but I also want to build on what's been strong about the past work. It's hard to figure out what to retain or what to give up, particularly when you have external forces encouraging you to make a specific kind of painting.

Gay Dead Satan, 2020,

oil and acrylic on panel with frame, 45 x 32 inches

What external forces and what kind of painting?

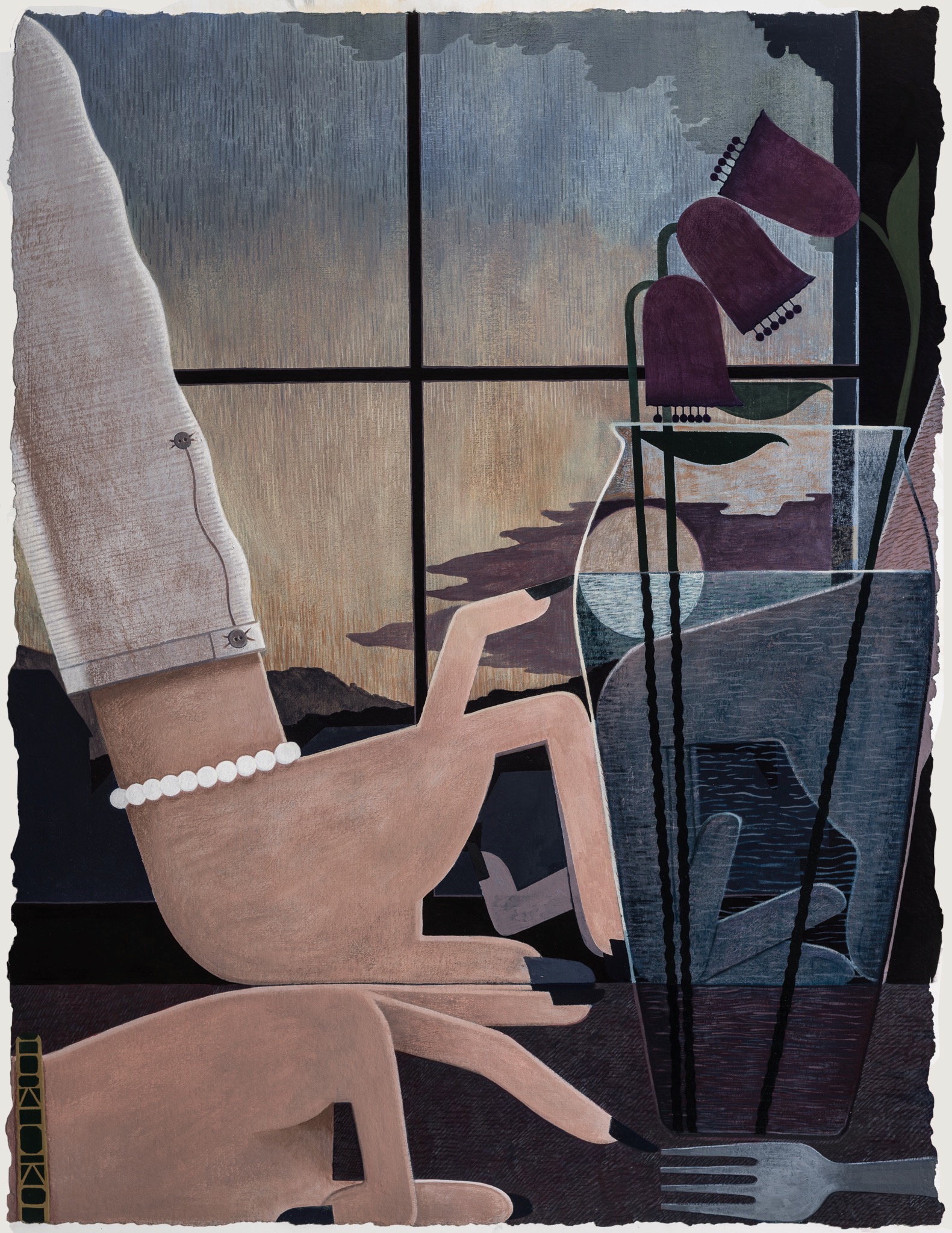

Everyone really liked the hand paintings from the show, and I think that if I continued making them, people would buy them. The conceit of those paintings was that the hands look like human figures, but I don't really know any more hand gestures that are anthropomorphic in the right way. I don't want to put any random hand in for the sake of replicating one half of the concept, even though I don't actually know how readable it is as a human figure to a viewer who may just like the effect of a hand in front of a window.

I want to make more work that's like the abstract work from the show, that was more fun to me. Making it was more interesting - the collage pieces allowed me to access more discourses. I want to go that way and I want to have some fun, to get a little wilder and a bit less cohesive. That's what I'm trying to figure out right now.

I also have this construct in my head that there's a painting I can do that fulfills every single thing I want out of painting that large, all at the same time, and that's making me feel really crazy. The hands and the realism and the collage. There's some Nicole Eisenman paintings that do every single thing. There's some Dana Schutz paintings that do that, too, and I'm trying to figure out what version of that is for me.

I want to make more work that's like the abstract work from the show, that was more fun to me. Making it was more interesting - the collage pieces allowed me to access more discourses. I want to go that way and I want to have some fun, to get a little wilder and a bit less cohesive. That's what I'm trying to figure out right now.

I also have this construct in my head that there's a painting I can do that fulfills every single thing I want out of painting that large, all at the same time, and that's making me feel really crazy. The hands and the realism and the collage. There's some Nicole Eisenman paintings that do every single thing. There's some Dana Schutz paintings that do that, too, and I'm trying to figure out what version of that is for me.

![]()

Submission, 2020,

oil and acrylic on panel with frame, 30 x 23 inches

When you sit in front of the canvas, is the goal usually to solve some sort of problem?

That's exactly what it is. I'm very concept driven as an artist. I feel like it's sort of embarrassing to say that you're a conceptual painter, because I'm not sure if that's even a thing, but I am very concept driven.

I want to do a painting of three people falling at the same time into water. There’s these three gay guys in history who committed suicide by jumping into water, and I want to do a painting that superimposes them onto one another. I want the painting to be upside down so that the falling figures themselves are right side up; I want there to be a splash; and I want it to be in a way that's interesting but isn't Cubist. I want the figures to be discrete from one another, so not abstract expressionist; and I want there to be room in the background of the painting to put lots of different images that are collaged in.

So that’s what's going on in my head, I don't have any specific colors, or forms yet, just conditions. I think I might have to loosen the conditions and just give myself a bit of a break.

I want to do a painting of three people falling at the same time into water. There’s these three gay guys in history who committed suicide by jumping into water, and I want to do a painting that superimposes them onto one another. I want the painting to be upside down so that the falling figures themselves are right side up; I want there to be a splash; and I want it to be in a way that's interesting but isn't Cubist. I want the figures to be discrete from one another, so not abstract expressionist; and I want there to be room in the background of the painting to put lots of different images that are collaged in.

So that’s what's going on in my head, I don't have any specific colors, or forms yet, just conditions. I think I might have to loosen the conditions and just give myself a bit of a break.

I saw that you do a lot of work in Rhino. I’m wondering how that works with the layering of images, because the way that things fit together so distinctly feels like a puzzle. At what point in your process do you start piecing things together like that?

There's a painting that has the stars and the planets in it, and that painting is one in which I used Adobe Illustrator and Rhino sort of interchangeably. They're both vector based, and I find that Adobe Illustrator works better with a vinyl cutter. I've moved more into Adobe Illustrator, for example, for the new painting I'm working on, I will probably block out the main three figures and then I would take a picture of that and square it in Photoshop, then I would bring it into Illustrator, and start moving things around.

The work usually begins with drawing or painting because I’m a painter and not a graphic designer; I do want gesture and spontaneity to be the basis of the painting rather than a vector file. I'll move in and out of Illustrator or Rhino, I'll do some moves in Rhino, then bring the vinyl cutter and stencils in, and then I'll work on it outside of that to build up texture.

I find that the movement in and out of digital makes the painting reveal itself to you more mysteriously. Like if you were running away from someone, and then you swept away your footprints to obscure your trail. It's a way of going deeper into a world, diving in, and making your path a little bit less apparent. Not that I want to escape from the viewer, but I think it's a really interesting way of creating a complicated breadcrumb trail from your starting point for the viewer. I do like jumping in and out of Rhino or Adobe Illustrator throughout the process, because it confuses the eye about what's a brush and what's graphic, and I like that complication.

The work usually begins with drawing or painting because I’m a painter and not a graphic designer; I do want gesture and spontaneity to be the basis of the painting rather than a vector file. I'll move in and out of Illustrator or Rhino, I'll do some moves in Rhino, then bring the vinyl cutter and stencils in, and then I'll work on it outside of that to build up texture.

I find that the movement in and out of digital makes the painting reveal itself to you more mysteriously. Like if you were running away from someone, and then you swept away your footprints to obscure your trail. It's a way of going deeper into a world, diving in, and making your path a little bit less apparent. Not that I want to escape from the viewer, but I think it's a really interesting way of creating a complicated breadcrumb trail from your starting point for the viewer. I do like jumping in and out of Rhino or Adobe Illustrator throughout the process, because it confuses the eye about what's a brush and what's graphic, and I like that complication.

![]()

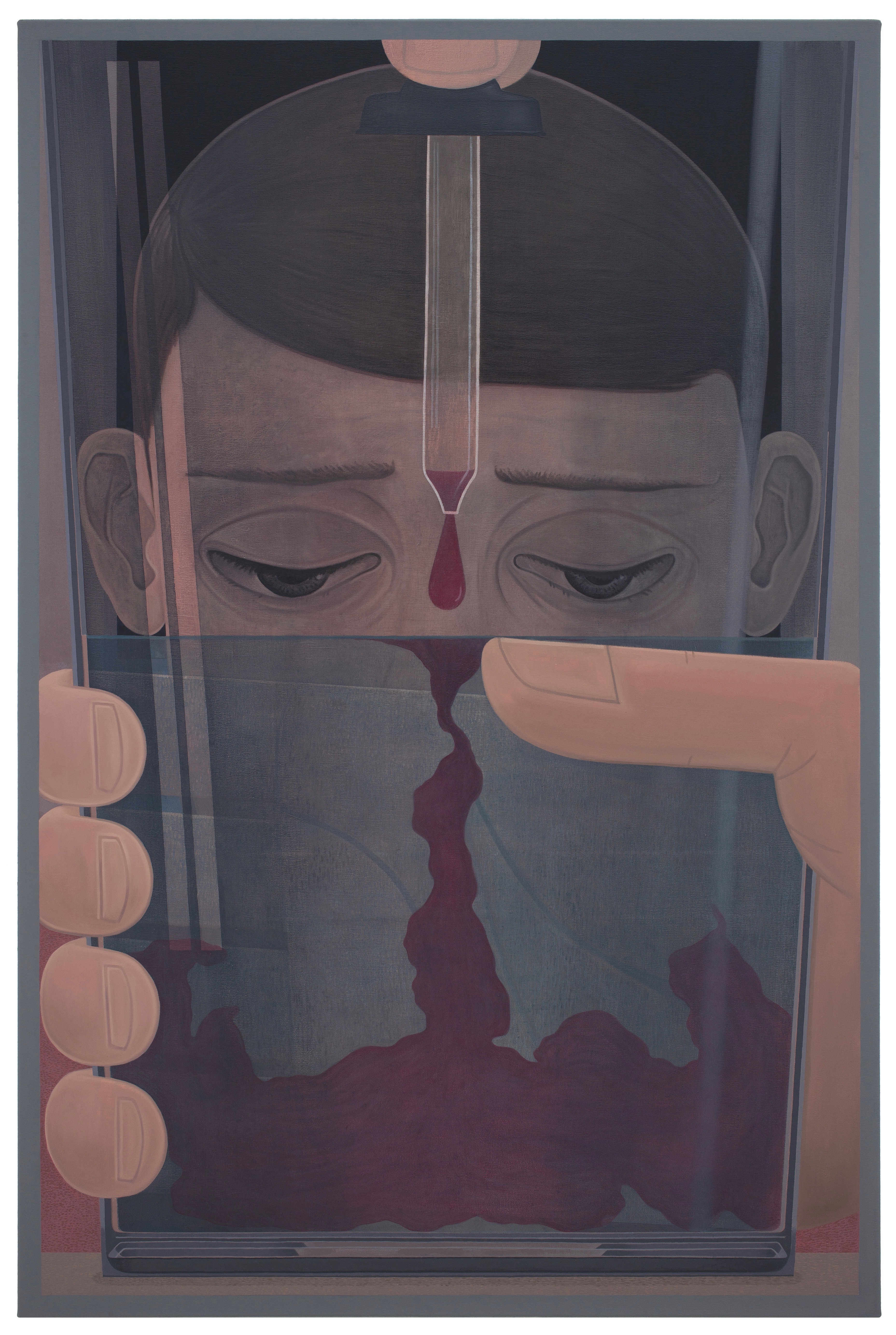

ECT, 2020,

oil and acrylic on panel with frame, 45 x 32 inches

With the vessel paintings, I occasionally used Maya, a 3D modeling program. Sometimes, I would paint a painting and then render a glass in front of it so that the refractions would be optically correct, but that was a real nightmare, and I give myself permission not to do that anymore. I've always worked really heavily with Photoshop and Illustrator throughout the process. I don't do a lot of studies on paper and I'd say probably 50% of the work is done on the computer, just trying out different compositions, building up different layers.

Working on a computer allows you to have a degree of control that I think is both good and bad, because I do think there's something to be said for when a painting is made entirely on the canvas, and you can see that the artist is really getting into the paint. I think that's a really special sensation that is very unique to painting, but I'm not a good enough painter to do that, so I try to use technology and programs to compensate for what I perceive as a lack of technical skill. There are some painters who have a really strong physical connection with a painting and they can intuitively work through it on the canvas but I can't do that, I have to be much more structured and schematic.

Working on a computer allows you to have a degree of control that I think is both good and bad, because I do think there's something to be said for when a painting is made entirely on the canvas, and you can see that the artist is really getting into the paint. I think that's a really special sensation that is very unique to painting, but I'm not a good enough painter to do that, so I try to use technology and programs to compensate for what I perceive as a lack of technical skill. There are some painters who have a really strong physical connection with a painting and they can intuitively work through it on the canvas but I can't do that, I have to be much more structured and schematic.

![]()

Prelapsarian Sill, 2018,

28 x 21 inches

When you were on the podcast Sound and Vision, in 2018, you were speaking about how your paintings, or at least the subject matter of the work, has to relate to the real in some way. Does this back and forth from digital to analog aid in that?

I think it's really interesting that you bring that up. I used to be really interested in Lars von Trier and the Dogme 95, this idea of having a set of rules that define the creator’s relationship to realism. And there was a set of rules that I had in mind, because I thought it would produce the most honest work.

It's awesome that you had that question, because I do think that that's something I've sort of loosened up on with the new, more abstract work that is much less iconic or rendered. I realized that these rules were really limiting. I was painting myself into a corner for a kind of moral purity that no one else was noticing, it was just me being strict with myself in a characteristically self torturous way. I just realized that the whole thing was a construct, there was actually nothing real about these rules and there is nothing more or less pure about an experience of a painting that is abstract or relates to something metaphysical than something realistic. So I decided that I could just paste pictures on the canvas because there are no rules, and that was a really empowering realization.

It's awesome that you had that question, because I do think that that's something I've sort of loosened up on with the new, more abstract work that is much less iconic or rendered. I realized that these rules were really limiting. I was painting myself into a corner for a kind of moral purity that no one else was noticing, it was just me being strict with myself in a characteristically self torturous way. I just realized that the whole thing was a construct, there was actually nothing real about these rules and there is nothing more or less pure about an experience of a painting that is abstract or relates to something metaphysical than something realistic. So I decided that I could just paste pictures on the canvas because there are no rules, and that was a really empowering realization.

![]()

The Touch, 2016, acrylic on paper,

22 x 30 inches

The Touch, 2016, acrylic on paper,

22 x 30 inches

Another part of that realization was to stop trying to make work for an audience that I wanted to elicit a specific reaction from or trying to control the audience with my own decisions. I’m trying to have more fun with the viewer, and, honestly, being a disciplinarian is really unsexy—and I mean sexy in a very abstract way—a bit of sexiness and fun and joy never hurt anyone.

When I say “real,” and I believe that I said this in the podcast, I also mean it in a literary way. It's not realistic in the way that it looks, but that it pertains to a real world. Some of the paintings in the show are not realistic, and those are actually the paintings that I had the most fun with and that I think are the most intellectually complicated. They're not the paintings that people liked the most, so in terms of sticking to the real: sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't. I’m trying to figure out which is which–it's really hard. Painting is really hard. I'm feeling that acutely today.

When I say “real,” and I believe that I said this in the podcast, I also mean it in a literary way. It's not realistic in the way that it looks, but that it pertains to a real world. Some of the paintings in the show are not realistic, and those are actually the paintings that I had the most fun with and that I think are the most intellectually complicated. They're not the paintings that people liked the most, so in terms of sticking to the real: sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't. I’m trying to figure out which is which–it's really hard. Painting is really hard. I'm feeling that acutely today.

![]()

Fake Tear, 2016,

30 x 24 inches

Concerning the vessels, is there a bodily relationship between the symbols or maybe the idea of the body as a vessel?

Yes, absolutely. Before I did painting, I was getting my PhD in English, and I took a class with someone who specialized in medieval theology. We talked a lot about the vessel and the body in religion. There are all of these poems from the 14th century about the body as… like... a cup. There's also the Song of Songs, that famous poem about two lovers in which they describe each others’ bodies as temples, and the body as a set of objects... pearls, fountains, doors. I was really inspired by that. It’s kind of a weird way of discussing religious embodiment that I liked. So that informed how I see the body symbolically.

There's such an interest in the natural but also the medicinal. What is your relationship to Religion and astrology? With the tinctures and vials, there also seems to be an interest in altered states. What is this murky place where all of these things have their own validity?

The short answer to that is that I think a lot about holiness and how even if you're not attached to one type of religion, or one set of beliefs, that there are symbols that unify all religions. Everyone is pretty interested in the moon, the sun, et cetera. There's this literary theorist named Northrop Frye, who talks a lot about how one of the reasons narratives even exist is because of the organizing principles of the 4 seasons. He explains how comedy is spring, summer is romance, fall is tragedy and winter is satire and how that connects to the way people experienced the harvest, the natural world. He's not really religious per se, but it is sort of a spiritual belief that posits that our experience in the natural world connects to meaning in general. I am interested in meaning, like metaphysical meaning, and I do think that I have a spiritual belief in meaning... that things are in fact meaningful on a grand scheme, even if it’s symbolized or experienced differently on an individual level.

So my paintings are really not nihilistic–I would paint the sun because when I look at the sun, I feel like I am connected to a sense of greater meaning. So that's my answer via religion, it's spirituality but it’s also metaphysics and ontology et cetera. But I'm not religious at all, I was raised Reconstructionist Jewish, I got bar mitzvahed, but I feel very little connection to that religion other than culturally.

So my paintings are really not nihilistic–I would paint the sun because when I look at the sun, I feel like I am connected to a sense of greater meaning. So that's my answer via religion, it's spirituality but it’s also metaphysics and ontology et cetera. But I'm not religious at all, I was raised Reconstructionist Jewish, I got bar mitzvahed, but I feel very little connection to that religion other than culturally.

![]()

Creationista, 2019,

48 x 28 inches

Creationista, 2019,

48 x 28 inches

And yes I am also interested in wellness. My relationship to the body is kind of weird, in that I was really, really sick for a long time, mysteriously sick. There are periods of my life where I could barely walk, and then I'd be well, and then sick again, and it just made me totally insane. And I had no idea what was wrong with me. I was sick and it was just really negatively affecting my life. Then, in 2017, I got diagnosed with an autonomic nervous system disorder called postural orthostatic tachycardia, which is basically when your body can't regulate your blood pressure when you're standing or sitting. It's only when you're lying down that your body's normal. I was really, really sick in 2016 and ‘17 when I was making the medicine paintings and the therapy paintings so I absolutely, 100%, think that my interest in medicine and wellness was autobiographical.

![]()

B12, 2018,

60 x 40 inches

Then I started taking these steroids in 2017 that have changed my life. I'm living like a normal person now, and I think that it's not surprising that the work has gotten a little more colorful and less morose, a little bit more fun. In terms of altered states, I take ketamine treatment for mental illness stuff but that’s the extent of it. I do think that if someone needs mushrooms to get to the truth, someone needs the Bible, and someone just needs to be out in their garden, all of those things are equal to me, but I do believe they are all connected to a sense of understanding or wanting to understand greater meanings. And it's just circumstantial that I would have picked a painting about ketamine, because that's sort of what was happening to me at the moment.

![]()

Ketamine, 2020,

oil and acrylic on panel with frame, 45 x 32 inches

I want to ask about the swords, which are a recurring presence. There’s that bit in Maggie Nelson’s “The Art of Cruelty,” where she talks about the sword as symbolizing not niceness but goodness or the necessary protection of what is good. What are you getting at with the swords?

It's really funny that you asked that question, because it's a totally reasonable question to ask –there's so many swords in the paintings–but I actually don’t know. Maybe I’m just a dork because I'm attracted to medieval imagery. I think it's cool, it feels epic. It’s similar to how I like how cats look and act, so I put them in my painting. Although I did have cats.

But when I look at a lot of religious imagery there are a lot of swords, and they are connected to ideas of holiness and spirituality more than, for example, axes or even guns. You're right, they are more connected to “good” things, meaning and order. People will hold a sword and it'll represent order or the promise of a sort of justice. I also just don't see the devil [in the paintings] getting killed by anything other than a sword, you know? It would be too postmodern to have someone kill the devil with a gun, it doesn’t feel allegorically pure. That's what I mean when I talk about realism. It's also that I don't ever want to paint a painting of the devil getting killed by a laser or something that feels wacky or too contrived.

A lot of the choices I make are just based on affinities. I don't really have a good explanation for it other than maybe that I liked video games with swords when I was a kid.

But when I look at a lot of religious imagery there are a lot of swords, and they are connected to ideas of holiness and spirituality more than, for example, axes or even guns. You're right, they are more connected to “good” things, meaning and order. People will hold a sword and it'll represent order or the promise of a sort of justice. I also just don't see the devil [in the paintings] getting killed by anything other than a sword, you know? It would be too postmodern to have someone kill the devil with a gun, it doesn’t feel allegorically pure. That's what I mean when I talk about realism. It's also that I don't ever want to paint a painting of the devil getting killed by a laser or something that feels wacky or too contrived.

A lot of the choices I make are just based on affinities. I don't really have a good explanation for it other than maybe that I liked video games with swords when I was a kid.

![]()

NARCISSUS, 2020,

oil and acrylic on canvas, 50 x 30 inches

These windows allow you both a sense of interiority and closeness that you're speaking to, but then also as a relationship between the inner and the outer worlds. And of course they act as a formal framing device.

There's an element of security of having a little frame. I think it makes me feel safe to have a finite area to make meaning within. I'm a little agoraphobic, and kind of an indoor person. I don't go out very much and I avoid big crowds. There's an element of pushing people away as well with the frame, like laying claim to the area within the frame and saying “this is mine, this is my space and I'm preparing it for you.” I'm sharing it with you, but it's not a shared space, they're very walled off. What you're seeing is a good description of that. I do really believe that the last 10 years of being ill really warped my brain into thinking a lot about self protection and having a safe environment that I can control. I would like to get rid of the frames, I just don't see that happening, and I don't really know why.

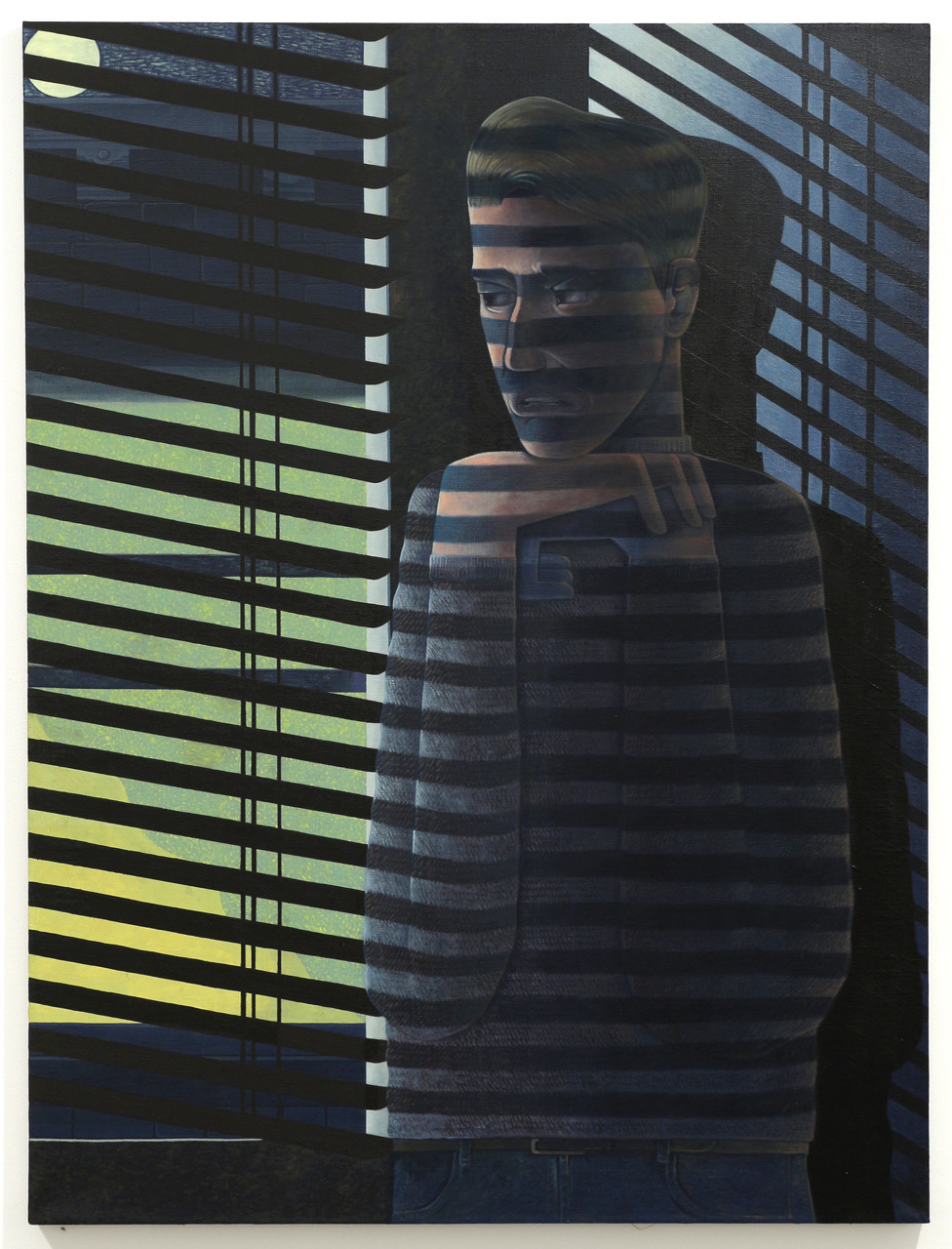

![]()

Shade, 2016,

48 x 36 inches

Do you feel like you’ve done it too much? Is that why you feel the urge to push it?

I'm suspicious of painters who rely on tricks or a small number of motifs. My favorite painters are ones who are constantly reinventing themselves. But there's still a lot to be done within the frame, and I don't think that I'm closing myself off to that. Even if I don't put the frame in, there's still the frame of the canvas that every painting has, obviously.

There’s a lot of painting that can be called poetic, but your work is heavily narrative based, and in that way a collection or a show of yours reads like a novel.

I think about that all the time. I don't produce a lot or work, and I definitely think that I make work like books–I really try to refine the meaning of the painting, so that they are fairly processed by the time people see them, or read them—if you will. That’s one of the reasons that I produce less. There are painters who work like a factory, where they make the same image over and over with small variations, and they might grow and change gradually, whereas I have to have the premise anticipate the form and the premises vary dramatically. They're like short stories, I guess.

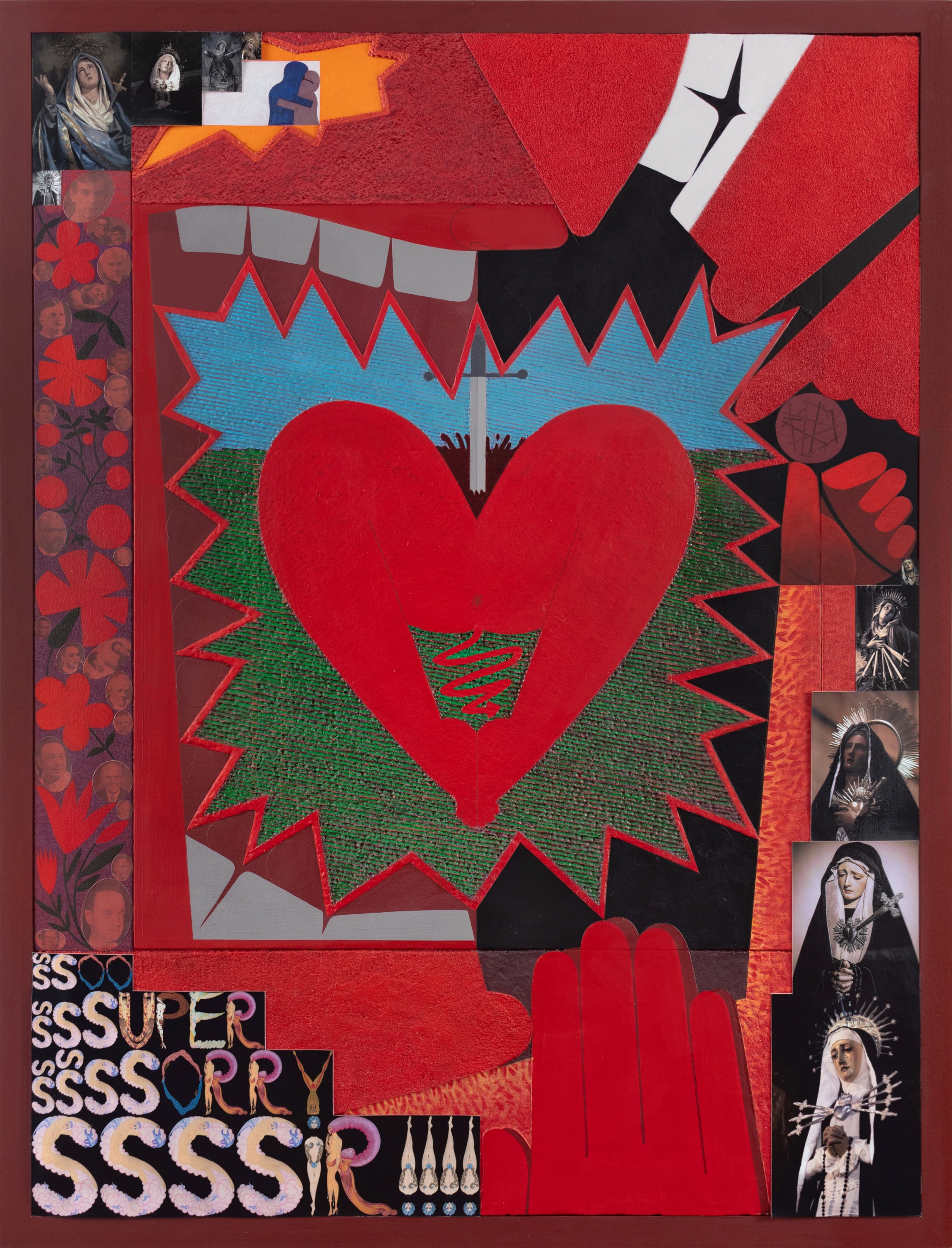

What is your relationship to gay elders and the “queer villain”?

People love to talk about gay elders and chosen family, and I think that language can sometimes be so tedious. It's true, but queer or gay identity is so much more multifaceted and interesting and more diverse than that; we don't have to make a hagiography of every single person that's like us. I wanted to be adversarial to people who need their identity reflected in a positive light all the time. I think that we need to explore every archetype—the good and bad sides—especially as white gay men become increasingly not a part of what I define as the queer community.

I just want to be real about people who are in power and how they wield power. The irony of including those people, some of whom I don't even think are that bad, is supposed to be an iconoclastic gesture. I was just trying to be obnoxious. I had placed a prominent gay politician who I personally don’t like on [the painting with gay villains] but then I thought, “Do I want to die on this hill?” I don't want to die on this hill by being snarky or holier-than-thou or an iconoclast and I don't want to alienate people with this painting. But I did really want to drag white gay men in the mud so that no one uses us as some Trojan horse of diversity for neoliberalism. I stand by that.

I just want to be real about people who are in power and how they wield power. The irony of including those people, some of whom I don't even think are that bad, is supposed to be an iconoclastic gesture. I was just trying to be obnoxious. I had placed a prominent gay politician who I personally don’t like on [the painting with gay villains] but then I thought, “Do I want to die on this hill?” I don't want to die on this hill by being snarky or holier-than-thou or an iconoclast and I don't want to alienate people with this painting. But I did really want to drag white gay men in the mud so that no one uses us as some Trojan horse of diversity for neoliberalism. I stand by that.

![]()

"so super sorry sir!", 2020,

oil and acrylic on panel with frame, 42 x 32 inches

Do you feel like your work has become more material driven as you move into collage?

The paintings from 2019 have a huge amount of texture in them, and they were an absolute nightmare to make. So much so, that I actually just stopped making them, I’m no longer interested in doing texture, because I think it impeded making a better painting. I think it looks cool when it’s finished, but there was this level of stress because you need to know everything that you're going to do before you do it. It was impacting my ability to be creative, or to change my mind without doing an incredible amount of labor.

A lot of those paintings are dremeled, there was so much dremeling. Honestly I'm just not getting paid enough to be that uselessly insane and detail-oriented anymore. I don't mean to be cynical or vulgar, but a lot of the decision making that has happened lately is because I perceive myself as not getting sufficiently compensated to follow all these draconian, self-flagellating rules that I set for myself or to do that much labor. I want to do what I want to do and what feels natural and not force myself to do so many things that damage my psyche. You know? At a certain point, I stopped trying to anticipate what I thought people would find value in and did what felt real and also what felt fun to me. A lot of my opinions come from a place of wanting to be funny about the present or trying to make a joke out of sadness or regret.

A lot of those paintings are dremeled, there was so much dremeling. Honestly I'm just not getting paid enough to be that uselessly insane and detail-oriented anymore. I don't mean to be cynical or vulgar, but a lot of the decision making that has happened lately is because I perceive myself as not getting sufficiently compensated to follow all these draconian, self-flagellating rules that I set for myself or to do that much labor. I want to do what I want to do and what feels natural and not force myself to do so many things that damage my psyche. You know? At a certain point, I stopped trying to anticipate what I thought people would find value in and did what felt real and also what felt fun to me. A lot of my opinions come from a place of wanting to be funny about the present or trying to make a joke out of sadness or regret.

![]()

Annunciation, 2019,

18 x 24 inches

There's definitely a meeting place between this levity and seriousness or sadness, especially with the recent works.

I like artists who really offer up their psyche to people, like Mike Kelly, for example. The idea that people could look at the devil's taint, and think “is this a self portrait?” That painting was designed to be proposed to the viewer as a self portrait. It's simultaneously totally a self portrait and completely not a self portrait. With that painting, I wanted to ask “How can I make a painting that's all projecting gay self-hatred? That would get people to think I hated myself.” That painting is kind of about a certain ambivalence about having any sort of identity at all. I think discourses about identity are super important and politically necessary but I don’t think every painting needs to have like an equivalent truthful identity. I am X so my painting is X, et cetera. It can be more complicated and non-linear than that. I can make paintings about things I may be, things I’m afraid I may be, things I’m not.

![]()

Devil's Dodge, 2020,

oil, acrylic and paper collage on panel with frame, 42 x 32. inches

I do love the mirroring of the asshole with the flower [Gay Dead Satan (2020)].

I spent so much time repainting the asshole. There were times when I made it a little bit more realistic, and it was so disgusting; the painting became visceral in a way where I couldn't even look at it. So, ultimately, I just made it clean and cute.

I really love that you'll talk about art that you find special on Instagram. I’m relating it to that whole Stendhal Syndrome thing. Do you have a first memory of feeling like that towards art?

In 2002, John Currin had a mid-career retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. It was my summer after my first year of college, and I knew nothing about contemporary painting. I knew that I liked painting, but I'd never learned anything about contemporary painting. Jeff Koons was the only contemporary artist I knew about. So I saw the John Currin show, and I just thought it was so funny; I didn't know art could be funny, or ironic and absurd. I now see this show as misogynistic but it still really influenced me. There was a particualr painting of a woman with a lobster on her head, and one with a candle on her head, she was basically the table for a still life. I liked that kind of topsy turvy still-life idea, I thought that was so funny.

Maybe it wasn't the first time I looked at art and thought “this is beautiful,” but it was definitely the first time I looked at art and thought “I want to make art like this, this actually feels correct, I feel connected to this.” I don’t have that feeling of “I went to go see Rothko and I cried.” While I respect that response, I've never felt that level of intensity. But when I saw Dana Schutz's paintings for the first time, they totally blew me away. There’s that painting of a figure with a face eating its own face. I thought “Whoa, how did you even come up with this? This is so funny.” As I've gotten older, I've moved back in time to Goya and Franz Hals paintings. Anyway, my answer is John Currin. Although, now he kind of sucks, I mean, he wasn't politically great then either, but he was funny…

It was the moment.

Yeah, it was the moment

Maybe it wasn't the first time I looked at art and thought “this is beautiful,” but it was definitely the first time I looked at art and thought “I want to make art like this, this actually feels correct, I feel connected to this.” I don’t have that feeling of “I went to go see Rothko and I cried.” While I respect that response, I've never felt that level of intensity. But when I saw Dana Schutz's paintings for the first time, they totally blew me away. There’s that painting of a figure with a face eating its own face. I thought “Whoa, how did you even come up with this? This is so funny.” As I've gotten older, I've moved back in time to Goya and Franz Hals paintings. Anyway, my answer is John Currin. Although, now he kind of sucks, I mean, he wasn't politically great then either, but he was funny…

It was the moment.

Yeah, it was the moment

![]()

The Prude, 2015,

40 x 30 inches

What was the first artwork that you made?

I remember learning that I knew how to draw. In first grade art class, we had to draw the person across from us at the table, and I was like “Oh, my god, I'm making a thing, and it looks like the person that I'm drawing.” I recall drawing the nose of the girl, and thinking “I'm drawing the same nose that I'm seeing.” I just remember that moment. Then, at my little school, they really lavished me with a lot of praise for being good at art, and I think it really fucked me up. I got really attached to the idea of being good at art so that people will like me. When I got to art school, I realized everyone was good, you know? A lot of people were better than me. And of course still are. It really damaged my ego, which I’ve mostly gotten over. Once you get over that, then you can be free! And now I'm just happy to hang out with artists and talk about painting… most of the time.

![]()

Combing, 2016,

40 x 50 inches

so super sorry sir!

Shulamit Nazaran, Los Angeles

January 16 – March 6, 2021

Visit Michael Stamm’s artist page.

︎: @michaelstammmmm