Jesse Mockrin

Jesse Mockrin’s reworkings of the art historical canon do not only recontextualize it for the current moment–nor do they simply seek to refute this history–her body of work flows along a lineage of painting that is immediately recognizable in its roots while giving new life to its contemporary forms. The point of departure from this descent is precisely where Mockrin’s paintings find their mystery and imminent lure.

Jesse Mockrin lives and works in Los Angeles.

Jesse Mockrin lives and works in Los Angeles.

What was your rose and thorn this week?

The thorn was that my three year old child was sick with a cold. Because of COVID, it shut our whole family down. We were all trapped at home, as we are anyway, but with no childcare. But thankfully he did not have COVID, so now we've been freed. The rose would be the very good phone conversation I had yesterday with that same child, which was really entertaining. I've never talked to him on the phone before.

The thorn was that my three year old child was sick with a cold. Because of COVID, it shut our whole family down. We were all trapped at home, as we are anyway, but with no childcare. But thankfully he did not have COVID, so now we've been freed. The rose would be the very good phone conversation I had yesterday with that same child, which was really entertaining. I've never talked to him on the phone before.

![]()

Weep into my eyes, 2019,

oil on cotton, 52 x 72 inches

When you were showing us your recent works, I wanted to ask you about the lighting and tonality of your paintings. Most of your early work is pretty realistic in terms of coloring and the overall tone of the painting. A lot of the stuff I've seen recently, the entire painting relies on certain overarching tones. What is the cause of that transition? Is the intention cinematic, surreal?

I've been thinking a lot about color this year: I started making works on paper for the first time, other than the pencil drawings I always make to generate ideas for paintings. I got paper made for oil paint, and I painted on it, and it turns out it works really well. Painting on paper was the gateway that allowed me to explore color more, in that it gave me a place to test things more easily than on a canvas. It’s freer psychologically and requires less commitment. I was interested in furthering my own understanding of color, and being more in control of the color space of the painting. I wanted to move the characters away from a realistic place and into a more experimental place, a more exciting place.

I started a green painting that I haven’t been able to finish, because it turns out green is a hard color to work with. When I started working on my next show, I was like, “everything's gonna be in this green palette.” And quickly that became, “oh, no, nevermind, everything's gonna be pink, sunset, evening, fire colors.” Solving that green painting will be a good project for me–figuring out how to make it work. Part of my motivation is that color is something that's hard, and it feels important to always keep pushing and learning.

I started a green painting that I haven’t been able to finish, because it turns out green is a hard color to work with. When I started working on my next show, I was like, “everything's gonna be in this green palette.” And quickly that became, “oh, no, nevermind, everything's gonna be pink, sunset, evening, fire colors.” Solving that green painting will be a good project for me–figuring out how to make it work. Part of my motivation is that color is something that's hard, and it feels important to always keep pushing and learning.

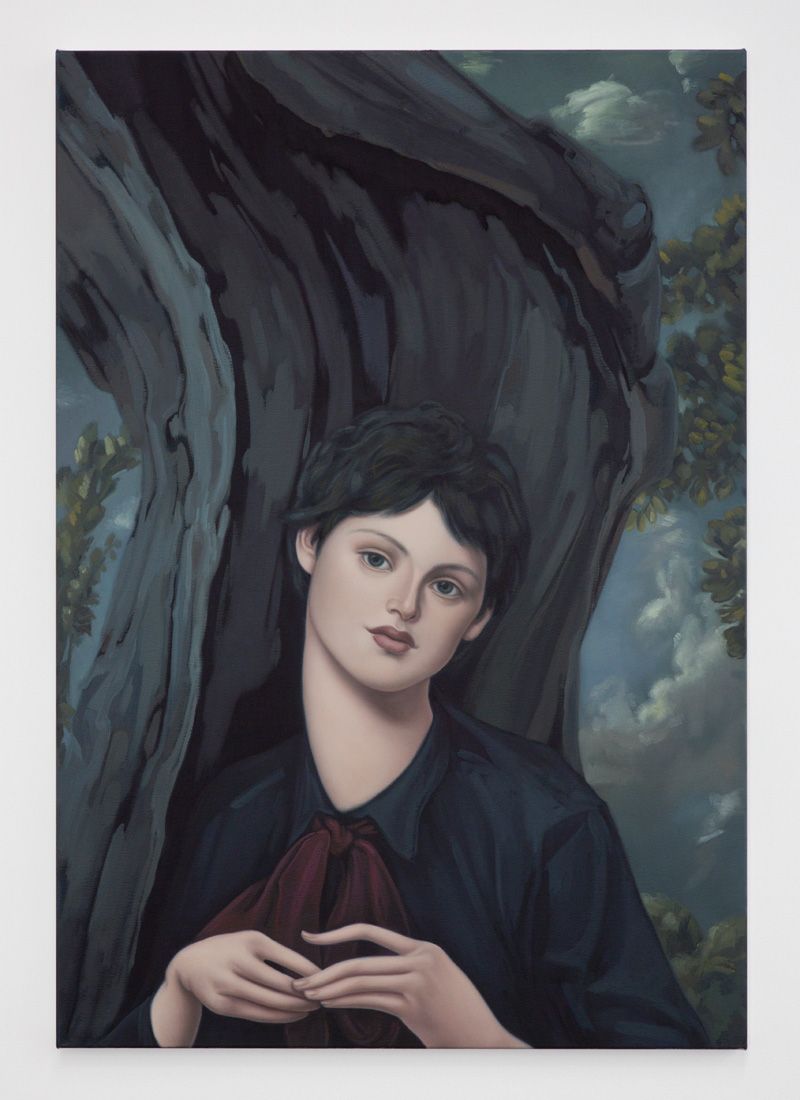

![]()

Approach, 2020

oil on linen, 26 x 18 inches

Is it that paper is lower stakes than canvas?

I think so. It's cheap and plentiful and it’s a great space for experimentation. It's low enough stakes that I can start and abandon something, which is different from the way I treat the works on canvas. I almost always complete the paintings I start on canvas, but I have many unfinished works on paper around the studio that function more as tests than as finished works.

How do you know when a painting works?

I guess when I'm satisfied with everything in it. If I'm looking at the painting and saying it's not working, it means the color doesn't have enough dimension or contrast to it, or those shadows don't make sense. So I guess it has to make a certain kind of sense. I don't want the work to be completely realistic, but I do want it to be convincing.

I know a lot of them are compositions that you’ve reimagined, but when you pull something out of thin air, is it hard for you to imagine what the lighting is supposed to look like?

Yeah, that pink diptych is based off of a black and white engraving. And so the color and the light had to be invented. I use natural light and take source photos to try to get a sense of where the light is coming from and how it works.

You’ve said previously that you prefer to work from photos. I read somewhere that you started in photography before you moved into painting. With your early photographs, was there a similar strain of exploration? How do they differ from your painting practice?

I went to Barnard College and took photography at Columbia, and the head of the department there was really into social documentary photography, like Lee Friedlander, streets of New York, Roy DeCarava, Gary Winogrand style photography. So at first I focused on documenting what was around me. Later, after I saw Cindy Sherman’s work, I started staging a lot of my photos too, using myself and my friends as models. The work was still focused on ideas around gender. The language of composition that comes from photography is what still influences my paintings–and I still end up staging photos to paint from.

![]()

Twisted, 2016,

oil on cotton, 42 x 29 inches

Old masters paintings are mostly disseminated as photographs or merely images. We know that they are paintings but the way that they’re presented to us is no different than another facet of visual culture.

Yeah, I think of their quality as “image” a lot. The way I consume historical paintings is as images, because I mostly see them on my computer screen or in a book. They're flat and reduced in size and their material quality is diminished. I think I am drawn to using old paintings as my source material because they are a record of visual culture and I can treat them as part of this larger image stream–a collapsing of high and low.

Do you feel like there's overlap between the paintings that you do now and the staged photographs more so than the documentary photographs?

Probably. For many years of my life, in various ways, I have had to ask friends, or boyfriends or my husband to help me with something by posing in this way or in this lighting. I think I’m used to constructing something in that way. In fact, I did a photo shoot this year for a painting. I didn't end up using the photos that much, but I had three friends helping. So yeah, in some ways I’m still working in the same mode. It’s kind of like posing mannequins for a window display, and that overlaps with how I think of the figures in my paintings–they aren’t really people but representations of the human body.

You mostly work from photos for portraits of living people, but is it important for you to get a feel for the person before you decide what you want them to do?

You also had that show with all the K-pop portraits.

Ah, that's true! In both of those cases, I feel like because they are celebrities, they live in the world of images too. My desire to paint them isn’t about them as real people–it's more about the images of them.

Vogue asked me actually if I needed to meet Billie Eilish, if I needed her to come pose in person, and they were worried because of how hard it would be to arrange with her schedule. And I was like, “Oh, no, I don't. Please just put her by a window and take a picture with some natural light.”

I don't know how actually meeting her would have changed things. I think I'm so interested in the image of her and the way she constructs her identity and her gender through her appearance, that working from photographs made perfect sense.

After painting those K-pop stars, I did meet one of them in person. That show was in Seoul, South Korea, and one of the stars came to the opening. And it was bizarre to actually meet one of them in person.

Vogue asked me actually if I needed to meet Billie Eilish, if I needed her to come pose in person, and they were worried because of how hard it would be to arrange with her schedule. And I was like, “Oh, no, I don't. Please just put her by a window and take a picture with some natural light.”

I don't know how actually meeting her would have changed things. I think I'm so interested in the image of her and the way she constructs her identity and her gender through her appearance, that working from photographs made perfect sense.

After painting those K-pop stars, I did meet one of them in person. That show was in Seoul, South Korea, and one of the stars came to the opening. And it was bizarre to actually meet one of them in person.

![]()

Billie with basket of fruit, 2020

oil on cotton, 33 x 27 inches

Did you know he was coming?

I did. What was weird was how unreal he appeared, which is not what I expected. He was like this flawless, ethereal creature in real life. I thought that he would look more real, not less. He also moved in these very specific ways for the camera. He was just so practiced at being an image. Anyways, it was very interesting. I enjoyed meeting him a lot.

Are you a fan of K-pop? How did that end up being the subject matter?

I'm not a fan of any particular band, or the music, per se. But I am a fan of the images that they produce, the image culture around K-pop, the music videos, and all of that. And I'm interested in fandom in general, and the way that fans feel a deep attachment to these icons. When I was in Seoul, we also went to a K-pop store that was six stories of merchandise–from themed cupcakes to photo collections to a hologram theater. It couldn’t have been any more obviously commercial. And yet, at the opening, people came up to me to tell me about their favorite star and how deeply they felt about them. One woman even dropped pictures of her favorite star off at my hotel the next day. I really enjoyed all of that–I think there’s something so complex and so powerful about the strength of emotion elicited in people by these images.

![]()

The Love Song, 2017,

oil on cotton, 28 inches diameter

Historically, portraiture was supposed to capture the entire likeness of someone, or their sensibilities, etc. What does portraiture mean to you? Do you think of your paintings as portraits?

I don't really think of them very often as real people. Sometimes that is my interest in looking at old portraits by Ingres or Sargent. I get this feeling that this was a person who really existed and that they're being kept alive in some strange way by being repainted in this moment. Part of what makes working with art history really satisfying is that the feeling of being in dialogue with this long chain of painting, and trying to make work that can somehow reach backwards into the thread of that conversation. My paintings are not meant to represent specific individuals, it’s more about ideas–ideas around what we project onto other bodies, onto an image of someone, from our own feelings and desires. They're like blank shells that we can project our own ideas onto.

Was there anything specific in your upbringing or Art History studies that made you interested in repurposing art history and mythology?

I was actually an art history major in college, with a minor in Visual Arts, because the two fields were combined at Barnard. Despite that, I don't know that I have a super good explanation for why I'm so interested in art history, I think I just became really invested in painting. In grad school, specifically, I became interested in the technical side of painting. The more I was interested in that, the more I was looking at art historical examples, and trying to figure out more about technique and how things were made. The more I looked at these things, the more they had their own life and layers of meaning that I was interested in decoding. But I didn't really embrace art history as a subject matter until a couple years after graduate school.

Then I finally just let myself appropriate directly from an old painting. I think it was partly due to the fact that I had these images around my studio all the time. I was always photocopying them or printing them out and piling them up around my space. And I was like, “well, maybe I should just do it,” even though it felt like something that was forbidden. All of that is such rich territory to make something from–I’m endlessly interested in it and it feels like maybe I shouldn't be doing it. So all that feels like the kind of complicated place that is good to be making work from. But it's not like I grew up around art historians or anything specific like that– everyone in my family is actually involved in the sciences in one way or another.

Then I finally just let myself appropriate directly from an old painting. I think it was partly due to the fact that I had these images around my studio all the time. I was always photocopying them or printing them out and piling them up around my space. And I was like, “well, maybe I should just do it,” even though it felt like something that was forbidden. All of that is such rich territory to make something from–I’m endlessly interested in it and it feels like maybe I shouldn't be doing it. So all that feels like the kind of complicated place that is good to be making work from. But it's not like I grew up around art historians or anything specific like that– everyone in my family is actually involved in the sciences in one way or another.

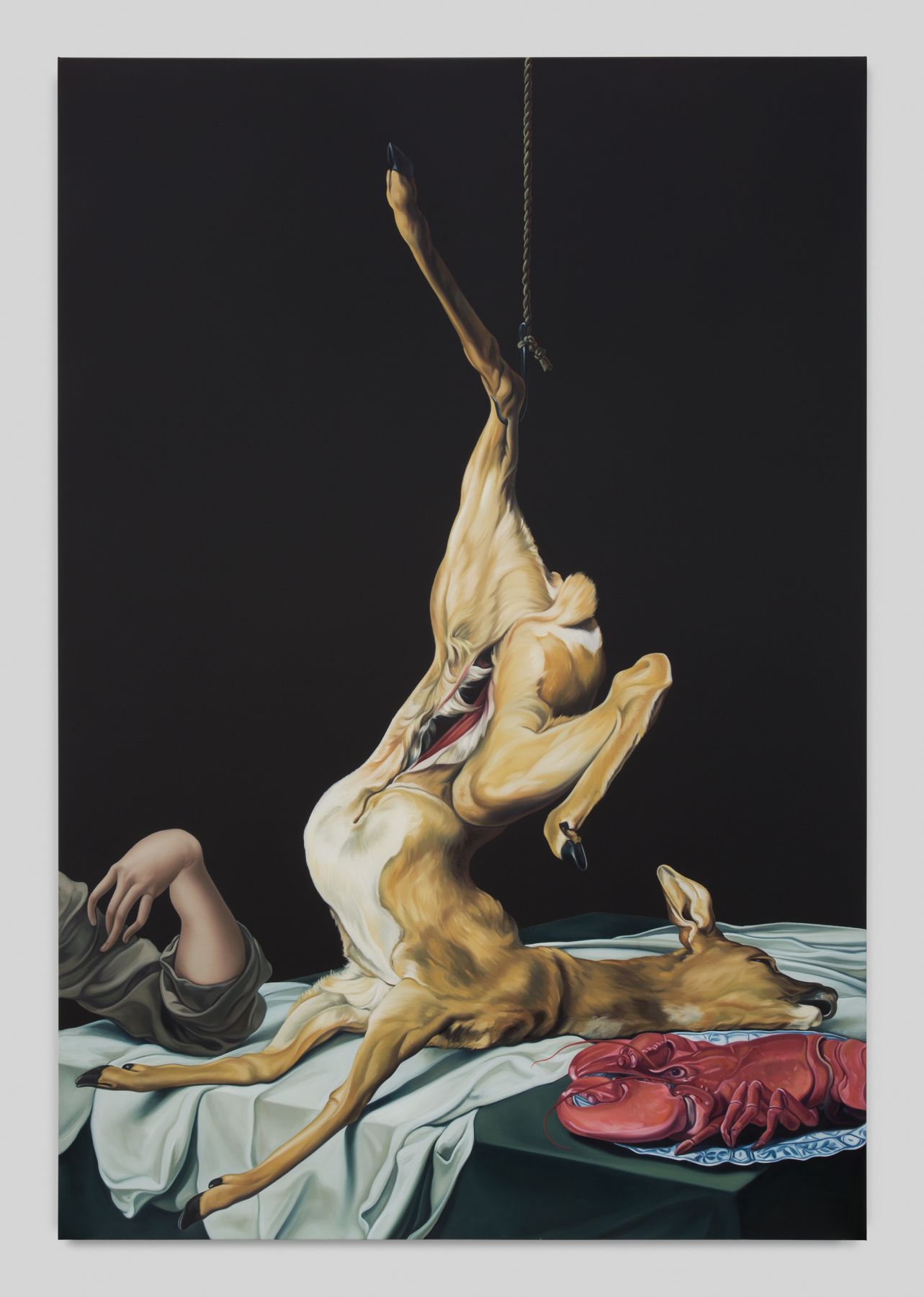

![]()

Quarry, 2019,

oil on cotton, 71 x 49 inches

When did you start painting?

I actually started painting in high school. I was always drawing as a kid, but then I had a great high school art teacher who introduced us to oil painting. Speaking of making people pose for you, I was really into Bonnard, and I had my best friend pose in the bathroom for me many different times, and made several paintings of her. I did painting in college too, but I was more focused on photography.

A lot of your earlier paintings are very still portraits against black backgrounds, and what you're doing now has a ton of action and violence. But there's a moment in between that, with something like, “The Enjoyable Lesson” (2016), with the ribbon around the dove’s neck, where it feels like there’s a moment of eeriness or tension or suspension, like the seconds just before action. Was it meant to be a suspenseful place?

I think a lot of that comes from the way the paintings are cropped. By zeroing in on a detail of a larger scene, as in The Enjoyable Lesson, there is an implication that something is happening here or about to happen that you should pay close attention to. That might create the eerie feeling you refer to, that things are a little uncomfortable and off kilter– and the compositions are often off center themselves. There's also the sense that the whole action is not being revealed to you–like there’s something just outside the frame that the viewer has to fill in.

The Enjoyable Lesson was part of a show that was inspired by paintings from the Rococo period, as well as contemporary men’s fashion images. That show was focused on the dissolution of the gender binary in both realms of visual culture–so maybe a sense of suspension (maybe more than suspense) relates well to the idea of being in between, not easily categorized, neither historical nor contemporary, neither male nor female.

But then I had a show of work influenced by Rococo and fashion open right before the 2016 election. As soon as that election happened, it felt like all this work about surface and visual pleasure and decoration and sensuality was out of step with the tensions in the world. So I think that going forward I embraced more aggressive imagery, and more of this Baroque style of action, which was deliberate. It felt more right to me, in relation to our times. The content of the art historical work became more foregrounded, and the work became more about the meaning of these mythological or biblical stories, as opposed to the foregrounding of visual pleasure and construction of space in the Rococo-inspired works. I like both.

The Enjoyable Lesson was part of a show that was inspired by paintings from the Rococo period, as well as contemporary men’s fashion images. That show was focused on the dissolution of the gender binary in both realms of visual culture–so maybe a sense of suspension (maybe more than suspense) relates well to the idea of being in between, not easily categorized, neither historical nor contemporary, neither male nor female.

But then I had a show of work influenced by Rococo and fashion open right before the 2016 election. As soon as that election happened, it felt like all this work about surface and visual pleasure and decoration and sensuality was out of step with the tensions in the world. So I think that going forward I embraced more aggressive imagery, and more of this Baroque style of action, which was deliberate. It felt more right to me, in relation to our times. The content of the art historical work became more foregrounded, and the work became more about the meaning of these mythological or biblical stories, as opposed to the foregrounding of visual pleasure and construction of space in the Rococo-inspired works. I like both.

![]()

The enjoyable lesson, 2016,

oil on cotton, 37 x 25 inches

Do you feel that by cropping the composition, you're asking the viewer to make assumptions and make that jump? Especially in the ones where they’re lined up, but the panels are different. You're making that immediate jump, and then it slowly dawns on you, like, “Oh, these don't quite line up.” Are you playing with expectations?

Yeah. With expectations, with perception, with making viewing more active. You can look at each panel of the diptych individually and then view them together and then pull them apart again. There’s a kind of time travel that happens between panels, and the fact that the images don’t line up highlights the dissonance of that jump. Things are left open-ended and the viewer hopefully gets to be more involved, completing the rest of the scene.

Do you think it's an act of liberation for these female subjects? I guess excluding Holofernes, as she’s literally chopping the guy's head off. Are you trying to liberate these figures from a fraught history, or with a time that they were less free?

I’m just trying to reframe the conversation to show or talk about how relevant these narratives still are. Sometimes the reframing heightens the violence that's inherent in the image. I come across things that are surprising to me in these art historical books, and the reframing of the work now is an attempt to show these past stories in our current context. When you go to an art museum, you see these old paintings in the context you expect to see them in–they can read as just more old paintings, relics of a past irrelevant time, recordings of people making odd gestures or engaged in incomprehensible actions. To most of us, the violence in them and the societal attitudes they reveal are almost invisible because we just accept them as part of this old time. But really it’s a continuum–my interest is to bring the relevance or the potency of these images into direct relationship with the context of our time.

![]()

The marks of a stranger, 2019,

oil on cotton, 85 x 118 inches

The marks of a stranger, 2019,

oil on cotton, 85 x 118 inches

It’s funny that at times you don’t see how strange these paintings or images are until someone paints it again.

I've looked at so many dead animal paintings without feeling any sense of death, you know? There are definitely some historical ones that are just super strange. I think everyone is like, “why is that baby peeing on her?” [Venus and Cupid, Lorenzo Lotto ] “And why is she tweaking her sister's nipple?” [Gabrielle d'Estrées and One of Her Sisters, School of Fontainebleau ].

Are these super dark backgrounds meant to pull the figures out of their context? It kind of feels like when you go to the Met or a museum, and you see this ancient necklace, and it's on black velvet. It feels very rooted in a museum’s visual language in some way.

I hadn’t thought about it that way, but I like that. The black works for me, because it’s both surface and space. It’s a color that can represent nothingness, as well as deep space, as well as the very surface of the canvas. And so that was my interest in isolating everything. I mean, I think that's why the necklace is on the black, it isolates it against a kind of neutral background–and the black creates high contrast.

That is part of what makes those paintings work on a formal level, the high contrast between light and dark, the chiaroscuro that's happening in those paintings. I like erasing the context. I think about the frame of the canvas kind of like the viewfinder of a camera, and these hands are reaching into the frame against a black background, like a glimpse inside a theater where all sorts of unlikely scenes are being constructed in real life. While the relationship to gravity in the work is often improbable, I never want it to be impossible, because I don’t want the work to verge into the totally surreal. With some of the larger paintings that have a little bit of ground across the bottom, the space functions sort of like a diorama or a theater set, or a tableau vivant. I guess the lack of context, being unmoored from time–that universal dramatic setting is what interests me.

That is part of what makes those paintings work on a formal level, the high contrast between light and dark, the chiaroscuro that's happening in those paintings. I like erasing the context. I think about the frame of the canvas kind of like the viewfinder of a camera, and these hands are reaching into the frame against a black background, like a glimpse inside a theater where all sorts of unlikely scenes are being constructed in real life. While the relationship to gravity in the work is often improbable, I never want it to be impossible, because I don’t want the work to verge into the totally surreal. With some of the larger paintings that have a little bit of ground across the bottom, the space functions sort of like a diorama or a theater set, or a tableau vivant. I guess the lack of context, being unmoored from time–that universal dramatic setting is what interests me.

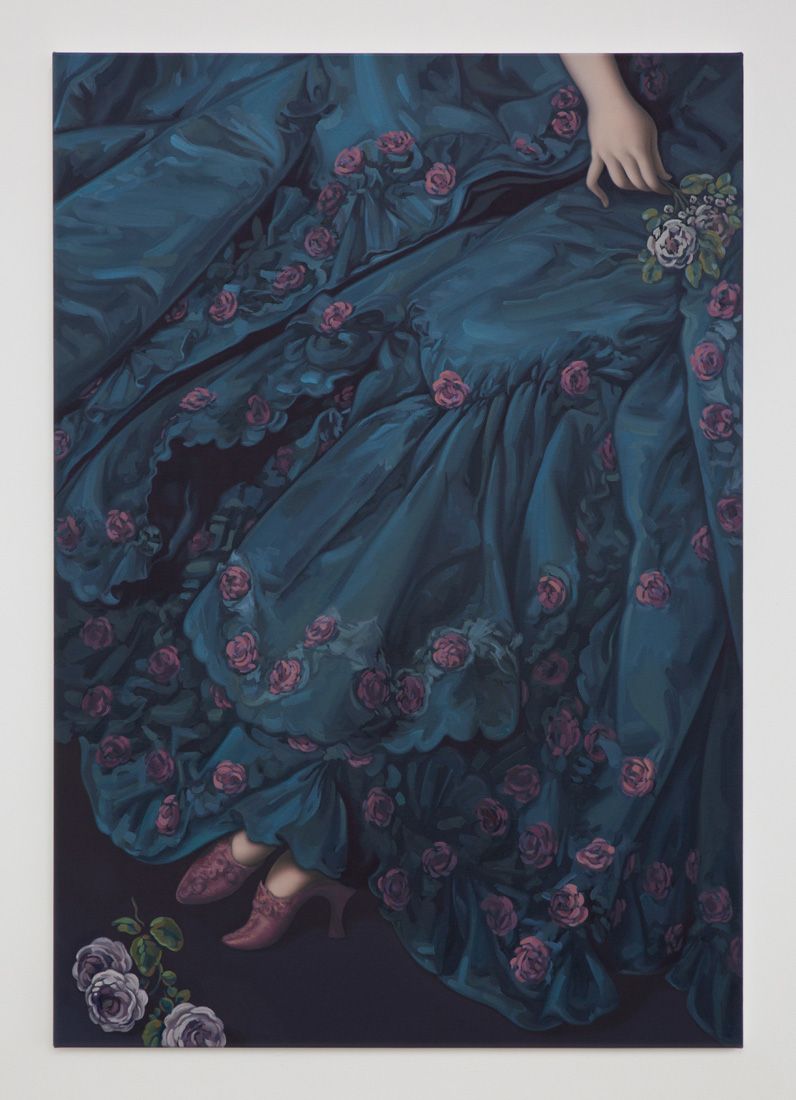

![]()

In Midstream, 2017,

oil on cotton, 74 x 102 inches

Especially with the curtains, I was seeing very theatrical references. It feels like a stage. Is there any special significance to the cloth or drapery?

Some of those works where the drapery fills the entire canvas were Rococo-inspired. So that came from an interest in draperies and the idea of them being associated with the feminine frills of the Rococo. But I would have the fabric take up all the space, and I was playing, again, with the surface construction; playing with depth and flatness so that the whole surface is covered by the fabric of a dress, or a curtain. The fabric can disrupt or enhance the illusion of space, and it adds the drama that I am both attracted to and feel embarrassed by, so that attraction/repulsion is an interesting space to explore. I also feel like the drapery is read as decorative and feminine and that if that’s the reason it’s repellent, then that is something to push back against.

![]()

The Garden of Love, 2016,

oil on cotton, 62 x 43 inches

The Garden of Love, 2016,

oil on cotton, 62 x 43 inches

Do you think about makeup culture, in terms of how it was in 18th century France? The Rococo was really big on the face, powder and rouge, etc. I feel like it's made a huge comeback now.

Yeah, I watched Euphoria on HBO and thought the makeup was really cool. On one of the paintings I made this year, I decided, “This figure should have red eyeshadow.” I was looking at pictures online of people with red eyeshadow, and people are doing such cool things now with makeup. I do think the way makeup enhances or obscures people’s faces is interesting, because it's so similar to the language of painting. In a painting, how does makeup read–as something on the face, or on the painting? I like playing with materiality in my work, where fabric flowers are juxtaposed with “real” flowers and wallpaper flowers, all depicted in the same material of paint. So the idea of paint and painting on the face is interesting. I often think that if this painting thing doesn't work out anymore, I could become a pretty good makeup artist. I’ve got an eye for detail and am pretty good at blending. So yes, I do think about makeup culture and I think it’s a rich territory that I would like to explore more.

![]()

Bloom, 2015,

oil on cotton, 62 x 43 inches

Why is your book/exhibition called “Syrinx?” And what was it like to be involved in a publication of a book of your work?

It was great to make a book, a lot of fun. The designer is a friend and she was amazing to work with, and she had the great idea of cropping the details of my work in unexpected ways, similarly to how images are cropped in my paintings. It was also really satisfying to combine works from different times and shows within the space of a catalog. My favorite part was probably the illustrated interview, where we combined images of my work with some of the historical sources they referenced. I don’t usually get to show those relationships and I liked how they inform each other when you see them together.

Syrinx was the name of the exhibition and the book because that series of work included a lot of abduction imagery, including one that was about the story of Syrinx, who Pan attempts to rape. She's a footnote in a story that's all about Pan, and his discovery of music, and the sublimation of desire into the act of creation. But this allegory is all at the price of her terror. So the show became named after her as a way of foregrounding her story. And it's a good word, so it made for a good title.

Syrinx was the name of the exhibition and the book because that series of work included a lot of abduction imagery, including one that was about the story of Syrinx, who Pan attempts to rape. She's a footnote in a story that's all about Pan, and his discovery of music, and the sublimation of desire into the act of creation. But this allegory is all at the price of her terror. So the show became named after her as a way of foregrounding her story. And it's a good word, so it made for a good title.

![]()

Syrinx, 2018,

oil on cotton, 68 x 94 inches

Visit Jesse Mockrin’s artist page.

︎: @jessemockrin