We spoke with artist Nolan Simon about the role that the internet plays in his paintings, Occupy Wall Street, Tumblr, his community of friends and collaborators, the perils of questioning one’s desires, and how all of this has informed his work over the years.

Nolan Simon’s most recent exhibition at 47 Canal, Cut off from the World, Attached to One Another, features images of his friends, lovers, and collaborators in closely cropped, paunchy, fleshy, and suggestive scenes. Just below the ironic, sexy surfaces of the paintings, the subjects seem to speak a shared, hushed language, one that viewers catch a glimpse or whisper of. They are mischievous yet earnest and attuned to one another. At one point in our conversation, he recalls a trip he took with a friend to the Barnes Foundation years ago, during which the silent— sometimes silly, and not always benevolent—communication between the Impressionists became legible to him. “It felt like they were doing what we were doing,” he told us.

When we spoke with Nolan over Zoom earlier this year, in January, it was amidst a slurry of political and cultural shifts—Trump had just been inaugurated, Twitter was imploding, the imminent ban on TikTok that never really was loomed in the near future, plus, David Lynch had just died. The personal or political relevance of those events is skewed in many directions, but for those active on Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok, users were inundated with hundreds of posts about them, likely without having asked for this deluge in any way. After all, the algorithm is devoid of choice or desire; it is fueled by your dumb attention rather than your thoughtful intention.

Nolan doesn’t shy away from the fragmented, chaotic landscape of internet platforms wholesale. With a sprawling and wide breadth of painterly languages at play, his canvases have been populated by art historical references, internet-historical references, and, like in his latest exhibition, intimate scenes of his own offline/online surroundings. This is less a total antidote to the visual culture and language of internet platforms but an incorporation of it in a way that is unlike the tyranny of the Timeline. It is perhaps closer to the internet of yesteryear, when users had at least a bit more agency in what showed up on their Dashboards or News Feeds.

Nolan Simon’s most recent exhibition at 47 Canal, Cut off from the World, Attached to One Another, features images of his friends, lovers, and collaborators in closely cropped, paunchy, fleshy, and suggestive scenes. Just below the ironic, sexy surfaces of the paintings, the subjects seem to speak a shared, hushed language, one that viewers catch a glimpse or whisper of. They are mischievous yet earnest and attuned to one another. At one point in our conversation, he recalls a trip he took with a friend to the Barnes Foundation years ago, during which the silent— sometimes silly, and not always benevolent—communication between the Impressionists became legible to him. “It felt like they were doing what we were doing,” he told us.

When we spoke with Nolan over Zoom earlier this year, in January, it was amidst a slurry of political and cultural shifts—Trump had just been inaugurated, Twitter was imploding, the imminent ban on TikTok that never really was loomed in the near future, plus, David Lynch had just died. The personal or political relevance of those events is skewed in many directions, but for those active on Twitter, Instagram, or TikTok, users were inundated with hundreds of posts about them, likely without having asked for this deluge in any way. After all, the algorithm is devoid of choice or desire; it is fueled by your dumb attention rather than your thoughtful intention.

Nolan doesn’t shy away from the fragmented, chaotic landscape of internet platforms wholesale. With a sprawling and wide breadth of painterly languages at play, his canvases have been populated by art historical references, internet-historical references, and, like in his latest exhibition, intimate scenes of his own offline/online surroundings. This is less a total antidote to the visual culture and language of internet platforms but an incorporation of it in a way that is unlike the tyranny of the Timeline. It is perhaps closer to the internet of yesteryear, when users had at least a bit more agency in what showed up on their Dashboards or News Feeds.

![]()

![]()

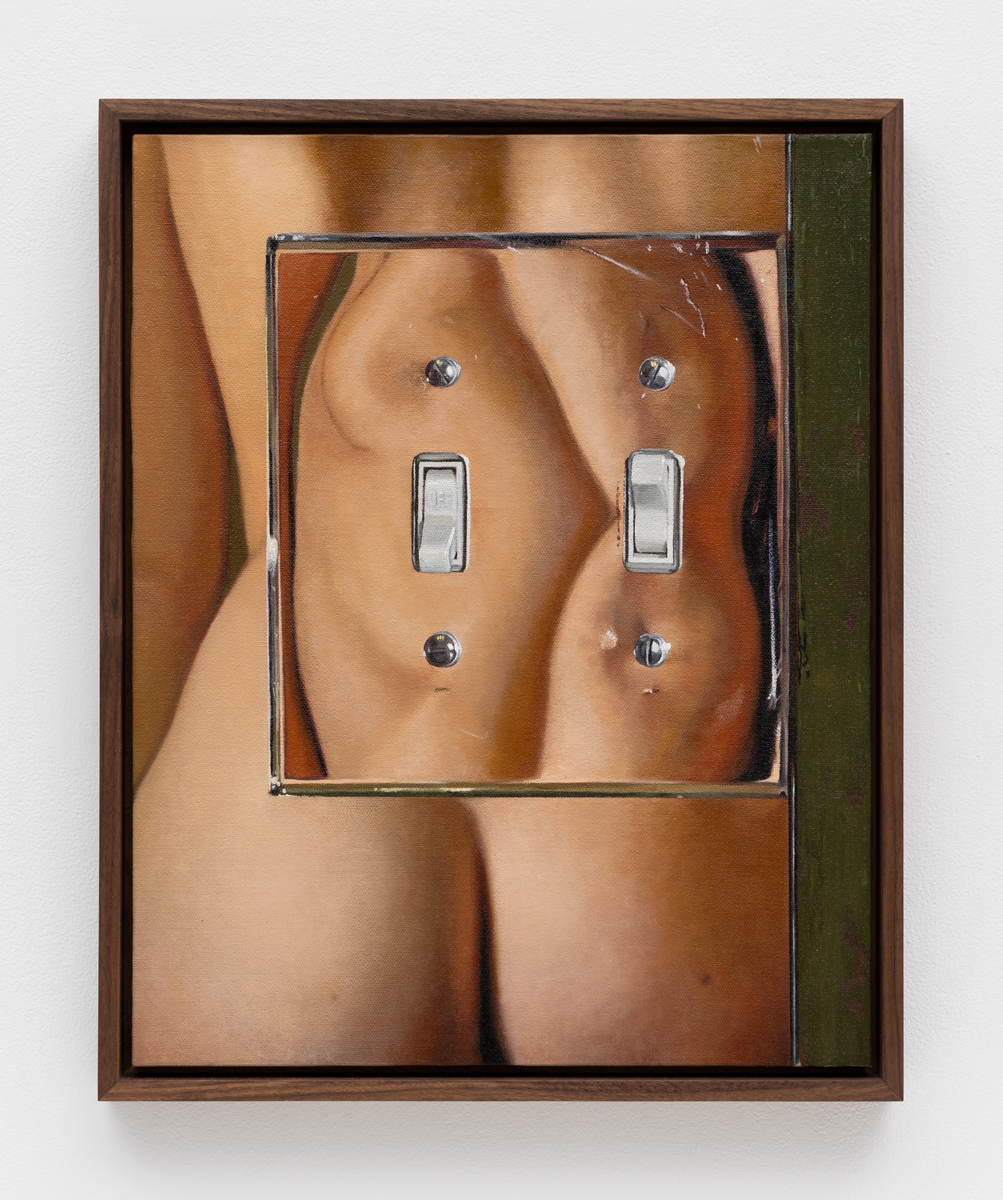

The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian at the Grand Guignol, 2025

oil, colored pencil and dye sublimation on linen, stretched over panel in artist’s frame, 28 x 22 inches

I'll start with a silly question, but does your Instagram handle [iqwnadjcvnaliuf] mean anything?

No. Back in 2011 I was part of a group of artists who tacked ourselves on to Occupy Wall Street as it was developing, and I got tasked with taking care of social media for the group, which at that time meant starting an Instagram and a Tumblr. I had to have an admin account that was separate from the primary account, so I just smashed my hand on a keyboard.

I was very skeptical of social media at first, even though I was the only person in the group who used it at the time. So, with a string of random letters I thought I could hide and people wouldn’t find me if they Google my name. It follows me everywhere at this point. Now, every time I run into someone in public and they ask to exchange instagram information, I'm always like, “let me type it in.” It makes for a more interesting social interaction, I guess. That's the silly story.

I was very skeptical of social media at first, even though I was the only person in the group who used it at the time. So, with a string of random letters I thought I could hide and people wouldn’t find me if they Google my name. It follows me everywhere at this point. Now, every time I run into someone in public and they ask to exchange instagram information, I'm always like, “let me type it in.” It makes for a more interesting social interaction, I guess. That's the silly story.

Install view, Portraits,

47 Canal, New York, 2015

Do you always write your press releases? I noticed a lot of the earlier press releases are written in first person. And then there's also this phrase that you repeat a couple times: “I'm terrible at telling jokes.” [Portraits, 47 Canal, 2015]

At first, I was really insistent on doing it myself, mostly because I felt like the gallery voice didn't work for the early exhibitions. They [the paintings] tried to operate on parallel levels, making statements that were plain and straightforward, and having a hidden subtext that an art world audience would pick up on. I always wanted my press releases to address both audiences. In theory, even though I know that the art world is very sequestered and doesn't reach a lay audience, I wanted there to be a language that civilians could pick up on.

“I’m terrible at telling jokes” comes from author David Markson who wrote a book called Wittgenstein's Mistress. It’s written in aphoristic first person. Every paragraph is a single statement. There are no chapters, and it just kind of rambles. As the story moves along, you start to notice it contradicts itself. It lays out statements and then says, “well, actually, maybe that statement is incorrect.” But in my case, I had a page to do it, and in Markson's book, it'll happen 20 pages later. I liked that internal incoherence, making statements that feel plain and obvious and then taking them back and saying, “actually, no, that's not quite right.” It kind of jived with my sense of myself as somebody who's always in doubt.

It's hard to get this across now, but during those early exhibitions, there were only a handful of people delving into realism with any earnestness. Coming out of that Cologne era of hyper irony and “deskilling” as a primary language, spending more than a day on a painting was really embarrassing. The consensus was, “why would you bother?”

“I’m terrible at telling jokes” comes from author David Markson who wrote a book called Wittgenstein's Mistress. It’s written in aphoristic first person. Every paragraph is a single statement. There are no chapters, and it just kind of rambles. As the story moves along, you start to notice it contradicts itself. It lays out statements and then says, “well, actually, maybe that statement is incorrect.” But in my case, I had a page to do it, and in Markson's book, it'll happen 20 pages later. I liked that internal incoherence, making statements that feel plain and obvious and then taking them back and saying, “actually, no, that's not quite right.” It kind of jived with my sense of myself as somebody who's always in doubt.

It's hard to get this across now, but during those early exhibitions, there were only a handful of people delving into realism with any earnestness. Coming out of that Cologne era of hyper irony and “deskilling” as a primary language, spending more than a day on a painting was really embarrassing. The consensus was, “why would you bother?”

In relation to your work with the peaches and the landscapes, you’ve previously talked about finding ways of making really traditional or conservative subjects seem punk.

Yeah, that really was the search, looking at John Miller and Jutta (Koether) and these other artists who were tiptoeing into this heavily ironized realism. Less so in Jutta’s case - she had some sincerity there. But I have to really emphasize that sincere painting was seen as philosophically irrational. The peaches exhibition [Paintings for school, Galerie Lars Friedrich, Berlin, 2013] came out of 4Chan before it was a neo Nazi website. (When It was an “ironic” neo Nazi website) One of the things that users on the /b/ (random) board would play around with was posting images that felt like images you weren't supposed to share, which were actually totally fine.

One of the things that came out of that was a handful of people posting pictures of white Japanese peaches from Japanese fruit wholesalers. Whoever they hired to photograph their peaches shot them in soft focus and it felt very erotic and strange. Every painting in that exhibition, I think there were 13 in the end, but 10 in the show were based on finding those photos online and appropriating them for the purposes of playing at having them be both banal and highly sexualized at the same time. Actually, a painting of peaches popped back up in the most recent show [Cut off from the World, Attached to One Another, 47 Canal, 2024].

One of the things that came out of that was a handful of people posting pictures of white Japanese peaches from Japanese fruit wholesalers. Whoever they hired to photograph their peaches shot them in soft focus and it felt very erotic and strange. Every painting in that exhibition, I think there were 13 in the end, but 10 in the show were based on finding those photos online and appropriating them for the purposes of playing at having them be both banal and highly sexualized at the same time. Actually, a painting of peaches popped back up in the most recent show [Cut off from the World, Attached to One Another, 47 Canal, 2024].

![]()

![]()

Basket of Peaches, 2013

oil on canvas, 9 x 12 inches

Basket of Peaches, 2013

oil on canvas, 9 x 12 inches

This is sounding similar to Jogging, but opposed almost diametrically to that. They went the route of what seems like full irony. Were you conscious of that at the time?

I didn't know them. I didn't know Brad. I've met them subsequently, but I was aware of it. Some friends of mine were kind of doing something similar, but on a much, much smaller scale.

I'm kind of happy and a little intrigued by you saying “diametrically opposed,” because I feel it, but I don't think that the work is always read that way. They're both definitely part of that “post internet” discourse. But what they were doing felt to me like something that resided in the computer, even when they popped out into the real world. Those early Timur Si-Qin sculptures of swords through Axe body spray felt like they were meant to live on the internet, almost in a modernist way, like it was wrong for the medium. They were trying to get a medium to do something that it wasn't supposed to do. And for me, painting was a way to play with images in a way that was native to the medium I was using. Almost right away it was about the internet, but it was also about history painting and, if you didn't get the internet stuff, it didn't matter.

I'm kind of happy and a little intrigued by you saying “diametrically opposed,” because I feel it, but I don't think that the work is always read that way. They're both definitely part of that “post internet” discourse. But what they were doing felt to me like something that resided in the computer, even when they popped out into the real world. Those early Timur Si-Qin sculptures of swords through Axe body spray felt like they were meant to live on the internet, almost in a modernist way, like it was wrong for the medium. They were trying to get a medium to do something that it wasn't supposed to do. And for me, painting was a way to play with images in a way that was native to the medium I was using. Almost right away it was about the internet, but it was also about history painting and, if you didn't get the internet stuff, it didn't matter.

“They were all this way of realizing that appropriation was changing, and figuring out new ways to play in it. Coming into that period of time, with the peaches, it was still very much about the internet being a giant sandbox, and I got to play in it. It took a long time for me to really metabolize what that meant for art, as far as I was concerned.”

Do you still feel like you're playing in the sandbox?

Oh, yeah, there's still a lot that I get out of it. I've gotten a lot out of developing friendships with people who are online content creators, rather than just kind of randomly wandering around. I feel like I keep bringing up Tumblr, and I have noticed that Tumblr has started to pop off again since Twitter has kind of gone nuts. So, you know, who knows? Maybe there will be a nostalgic return to the Tumblr era?

Stylistically with the peaches, you utilize this cross hatching that feels very reminiscent of the late 19th century and Impressionism. But it also almost feeds into the aesthetics of Apple’s Photo Booth and how you could select the crosshatch filter. It feels like it inhabits both territories.

I like things that feel like common sense. And by that I mean the first thing that your brain goes to – the first associations you have – because those are the ones that feel the most ideologically robust. Even early Photoshop, people were already trying to figure out ways to make things look like art, and what choices does that bring up? How do they stumble on ways to change images, how much work do they put into being able to break an image up into cross hatches or pixelate things?

It was much more about trying to think my way into making paintings that are about the history of painting, and using languages that would be legible to any audience, not just my peers. A lot of that came out of the same time, 2011, 2010, somewhere in there. I've been really close friends with Tobias Kaspar, the Swiss artist, for a long time. We drove out to see the Barnes Collection before it was moved to Philadelphia, so we could see it in its original state. That was a really revelatory experience. I went through a period of time where it felt like being too aware or too much of a fan of painting and art historical forms was for the historians. Like, “that's the dead stuff, and we're doing the live stuff.” All of my friends were hyper-focused on being as aware as you could be of the newest exhibitions, and the newest names.

Saying this, l feel like a grandfather, but it was just really important to be contemporaneous and going to the Barnes that first time was the thing that broke me into truly seeing Impressionism. It felt like they were doing what we were doing. They were making fun of each other, they were being ironic and silly and stupid sometimes, and that felt like something I hadn't seen. You could see that they're talking to each other in ways that aren't always just building on each other. Sometimes they are trying to tear each other down.

Coming out of that Barnes experience made me start looking for that stuff and trying to find these little references they made to each other. Another thing was noticing that Renoir would paint the same woman for a couple of years, the same person would appear over and over again. Courbet would paint the same woman over and over again. Being able to knit these things together gave it a kind of familiarity that I hadn't experienced before.

Doing this cross hatching, trying to make things look somewhere between Cezanne and Wayne Thiebaud, that felt like a fun way to add a level of language I didn't have. I wasn't a painter, I didn't study painting. At the time that I started making those works, I had made works on canvas, but I never thought of them as capital “P” paintings. It was important for me to have a reason to do that learning process in front of all my friends. It was an opportunity for me to try things out and play around and not feel embarrassed that I didn't know what I was doing.

It was much more about trying to think my way into making paintings that are about the history of painting, and using languages that would be legible to any audience, not just my peers. A lot of that came out of the same time, 2011, 2010, somewhere in there. I've been really close friends with Tobias Kaspar, the Swiss artist, for a long time. We drove out to see the Barnes Collection before it was moved to Philadelphia, so we could see it in its original state. That was a really revelatory experience. I went through a period of time where it felt like being too aware or too much of a fan of painting and art historical forms was for the historians. Like, “that's the dead stuff, and we're doing the live stuff.” All of my friends were hyper-focused on being as aware as you could be of the newest exhibitions, and the newest names.

Saying this, l feel like a grandfather, but it was just really important to be contemporaneous and going to the Barnes that first time was the thing that broke me into truly seeing Impressionism. It felt like they were doing what we were doing. They were making fun of each other, they were being ironic and silly and stupid sometimes, and that felt like something I hadn't seen. You could see that they're talking to each other in ways that aren't always just building on each other. Sometimes they are trying to tear each other down.

Coming out of that Barnes experience made me start looking for that stuff and trying to find these little references they made to each other. Another thing was noticing that Renoir would paint the same woman for a couple of years, the same person would appear over and over again. Courbet would paint the same woman over and over again. Being able to knit these things together gave it a kind of familiarity that I hadn't experienced before.

Doing this cross hatching, trying to make things look somewhere between Cezanne and Wayne Thiebaud, that felt like a fun way to add a level of language I didn't have. I wasn't a painter, I didn't study painting. At the time that I started making those works, I had made works on canvas, but I never thought of them as capital “P” paintings. It was important for me to have a reason to do that learning process in front of all my friends. It was an opportunity for me to try things out and play around and not feel embarrassed that I didn't know what I was doing.

The Waterfall (Eva), 2024

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

The body of work that utilizes masking tape and trompe l'oeil feels associated with this imagery as well. There’s all of this repetition that seems to hearken back to Tumblr, a platform where images are juxtaposed at random. How did you choose which images to place together? They almost feel like a poem, a bunch of different images that are meant to kind of coalesce into one thing.

I worked for years for Alexander and Bonin, who showed Sylvia Plimack Mangold. Back in the 60s and 70s, she did a series of fake tape paintings, which I always thought were the most interesting part of the work. So I stole that. I thought, here's an opportunity for me to create a reference to the grid and to play around. I could make that format over and over again and vary it in minimal ways, and have an opportunity to paint whatever I wanted. I think at the time what was important about it was the incongruity of the images. I was posting those images to my private Tumblr, You could go into the HTML and fuck with the format of your blog. So these Tumblr formatting options were making the choices for me. I was going through the images that I had posted and finding moments when they were doing interesting things next to each other. I would screen grab it, and that would usually be the reason that, say, one was a little higher than the other. Certain choices were taken off my plate, which felt good. Almost immediately after doing that show, the idea of the fake tape paintings felt pretty dead. It was rooted in such a particular period of time that within six or eight months I felt I couldn't keep doing it.

![]()

![]()

Spiritually Alive Pictures of Luxury, 2014

oil and acrylic on canvas, 48 x 36 inches

And is that when you moved into using the clothes as a landscape, the surrealism with these robes that have someone reading a paper?

I think the chest paintings were pretty early. They might even have pre-existed the Tumblr paintings and then popped back up afterward. Those chest paintings were an opportunity to do very simple, juxtapositions of two kinds of images that had their own contradictory logics. It became a way to deal with minimal depth and deep perspective in the same painting.

It might have been the shift of smartphones that precipitated that change. It was about the surface, but also about doing this worldly perspective, which is something I still think about. I think that impulse is universal at this point. There's not really a movement of painters doing landscape painting or cityscapes. We've all internalized the minimal depth of the screen.

I did a couple of landscapes around that time, I think I noticed that problem and tried to play with it. I did a painting of the entrance to the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, which was just a dirt road and the tree. Within the fake tape paintings, I copied a Gauguin painting, and then on Google images, I found an image that was a similar perspective of the same mountain, playing around with the fact that you can do a landscape painting from anywhere if you really want to. I was thinking about other ways to use that technology to produce something different. But pretty quickly those close cropped body images took over as a more native language.

It might have been the shift of smartphones that precipitated that change. It was about the surface, but also about doing this worldly perspective, which is something I still think about. I think that impulse is universal at this point. There's not really a movement of painters doing landscape painting or cityscapes. We've all internalized the minimal depth of the screen.

I did a couple of landscapes around that time, I think I noticed that problem and tried to play with it. I did a painting of the entrance to the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, which was just a dirt road and the tree. Within the fake tape paintings, I copied a Gauguin painting, and then on Google images, I found an image that was a similar perspective of the same mountain, playing around with the fact that you can do a landscape painting from anywhere if you really want to. I was thinking about other ways to use that technology to produce something different. But pretty quickly those close cropped body images took over as a more native language.

sweater painting, 2012

oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches

oil on canvas, 16 x 20 inches

You also curated that landscape show [LANDSCAPES, co-curated by Jake Palmert, Marlborough Gallery, 2016].

Yeah. That was weird. It was fun.

“what you're calling truthiness is a consistent need to decenter or question my own impulses or my own attractions. That has always been present in the work and my life in general. It’s a fundamental sense of the world that I have.”

I want to talk about this idea of “truthiness” that you mention, of authenticity being related to identity which is inherently fluid. This idea of how can a truth about identity or authenticity be a Truth? It feels like one of the things that ties all of these inquiries together is a self acknowledged truthiness, or of their existence as a painting. I was wondering if how you feel “truthiness” applies to your current bodies of work in comparison to the earlier, more overt ways of subverting that.

I do feel that, what you're calling truthiness, is a consistent need to decenter or question my own impulses or my own attractions. That has always been present in the work and my life in general. It’s a fundamental sense of the world that I have. I’ve had lots of conversations with my therapist where she'll say, “why do you have such a hard time understanding what you want?” My impulse is always to respond “how does anyone ever feel convinced of what they want?” How do you not immediately think “well, where did that want come from?”

Wondering about the origins of desire is the point of therapy, or at least psychoanalysis.

Right, that's where we're supposed to do that. On the one hand, that impulse has felt very generative for painting and noticing opportunities to try something or shift interests or shift perspective. But in my personal life, it's daunting. It does congeal into an inability. It's taking me years to decorate my home, because I'm always like, “do I like this? Is this actually something I want?” I will say, one of the places that has been the easiest for me to overcome that doubt is in erotically charged spaces. Things that my body is really drawn towards are easier for me to accept as a “yes.” In the bodies of work that I'm working on now, I try to start with a yes, an intuition.

Right now I'm reading Leo Steinberg’s The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Painting and Modern Oblivion, which is basically an extended thesis on why you see Jesus's penis in paintings. You don't see anybody else’s, so why do we see his?

It's like noticing in Impressionist paintings when they're poking at each other, it makes some impulses in Renaissance painting feel more native to me. I can enter into how those choices were made or why, which makes me feel like I have a key to unlock this human connection from 500 years ago. And honestly, I do just identify with perverts and weirdos and people who take those stories and images with a little bit of a wry, mischievous quality. I think that impulse to doubt has kind of morphed into an enthusiasm for mischief.

I now have a group of friends around me who I work with largely as my models. They're there with me, so they're willing to enter these strange places. We'll take all the parts of something and play around with it in a way that feels like the late stages of a sex party, where you're fooling around and flirting and having fun, and it doesn't have that initial anxiety. Everybody's comfortable around each other. We try to get there and play around with whatever imagery I have in mind.

Right now I'm reading Leo Steinberg’s The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Painting and Modern Oblivion, which is basically an extended thesis on why you see Jesus's penis in paintings. You don't see anybody else’s, so why do we see his?

It's like noticing in Impressionist paintings when they're poking at each other, it makes some impulses in Renaissance painting feel more native to me. I can enter into how those choices were made or why, which makes me feel like I have a key to unlock this human connection from 500 years ago. And honestly, I do just identify with perverts and weirdos and people who take those stories and images with a little bit of a wry, mischievous quality. I think that impulse to doubt has kind of morphed into an enthusiasm for mischief.

I now have a group of friends around me who I work with largely as my models. They're there with me, so they're willing to enter these strange places. We'll take all the parts of something and play around with it in a way that feels like the late stages of a sex party, where you're fooling around and flirting and having fun, and it doesn't have that initial anxiety. Everybody's comfortable around each other. We try to get there and play around with whatever imagery I have in mind.

The Illuminating Light (C.), 2024

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

There’s Sontag’s quote in Against Interpretation, “In place of a hermeneutics we need an erotics of art.” You can get caught up in a doom loop of interpreting yourself, but once you lead with eroticism or desire for desire’s sake, decisions are already made.

Obviously, everybody is hyper-focused on David Lynch right now, but I was watching his master class yesterday, and he talks a lot about how you get an idea, and what an idea is. I don't tend to jive with those esoteric, woo-woo relationships to inspiration. I much more think of them as triggers of memory or idiosyncratic associations. The way he talked about what you do with intuition felt to me like an erotics of our moment. He talked about fishing – you catch a fish, and then what do you do with it? That part felt the most relevant to me, because it was about the erotic. Those “yes” feelings and that playful stuff, those are all mechanisms for unlocking things in the images.

I take for granted that when I'm looking at something, or find myself attracted to an image or idea, I assume, right off the bat, that I don't fully understand what's going on, that there are parts of it that are occluded to me, and that inability to fully enter into something is actually part of what makes it useful to people. If it was too hyper-specific, it wouldn't be useful. I compare it to being invited to a party, and when you show up, everybody's already there and they're all doing some game or ritual that you've never seen before. You know that you're invited to this party, you're supposed to be there, but you have to stand back to watch and pick up on the unspoken rules.

That, for me, is how we interpret culture in general. We're thrown into these things, and we do them, or we don't. And you know, when you’re in Milan at the casino [Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II], you put your foot on the bull’s testicles and you spin around, and does it do anything? Do you really understand what's going on? I don't know, but I'm going to do it anyway.

One of my embarrassing go-to memories is Slavoj Žižek lectures. When I worked for Alexander and Bonin, I would put them on in the background and make boxes. He tells this anecdote about Niels Bohr working on the Manhattan Project, and a friend comes over and notices that he has an upside down horseshoe above his doorway. The friend says, “Niels, you're a scientist. You're not supposed to believe in that shit.” And he says, “oh, yeah, I don't believe in it. But a friend of mine told me that it works even if you don't believe in it.” That feels analogous to the way that I flow through the history of painting. I'm not an art historian, I'm never gonna know everything about this, but if I'm attracted to it, I know that I can pick it up and I can take it apart and I can use it, and I don't necessarily need to know why I make the connections I make. I just have to trust it.

Maybe this is a relevant thing to bring back up, about how spending more than a day on a painting would feel embarrassing. At this point, I can spend months on a painting. Sometimes I delve deep into painting techniques to learn how to build something. It's taken over as something that is interesting to me. This is something I do every day, I might as well get good at it. When I have this kind of erotic attraction to an idea or an image, I go through this process of playing with it, and pulling it apart, and finding places that I still feel confused by. Even in photo shoots with my partners, we'll throw out ideas to see what produces the weirdest or most compelling images. At that point, I still have more than a month ahead of me sitting with that image. So if it starts to die on the vine, if it doesn't have that question mark still lingering in it, this openness in it that I can still enter into and feel confused by – that's the thing that keeps them interesting to me, keeps them open.

I have a friend, Amanda, who lives in rural Pennsylvania. She takes these really beautiful photographs of herself, and she's one of the only people who I see consistently producing images that I feel both very attracted to and very confused by in a way that feels generative for me. We've developed a relationship where I'll make a painting a year based on a photo that she's taken. Otherwise I shoot everything, I do all the editing, and collecting of the objects and materials. It's really become this full on theater productions, in addition to all the painting.

I take for granted that when I'm looking at something, or find myself attracted to an image or idea, I assume, right off the bat, that I don't fully understand what's going on, that there are parts of it that are occluded to me, and that inability to fully enter into something is actually part of what makes it useful to people. If it was too hyper-specific, it wouldn't be useful. I compare it to being invited to a party, and when you show up, everybody's already there and they're all doing some game or ritual that you've never seen before. You know that you're invited to this party, you're supposed to be there, but you have to stand back to watch and pick up on the unspoken rules.

That, for me, is how we interpret culture in general. We're thrown into these things, and we do them, or we don't. And you know, when you’re in Milan at the casino [Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II], you put your foot on the bull’s testicles and you spin around, and does it do anything? Do you really understand what's going on? I don't know, but I'm going to do it anyway.

One of my embarrassing go-to memories is Slavoj Žižek lectures. When I worked for Alexander and Bonin, I would put them on in the background and make boxes. He tells this anecdote about Niels Bohr working on the Manhattan Project, and a friend comes over and notices that he has an upside down horseshoe above his doorway. The friend says, “Niels, you're a scientist. You're not supposed to believe in that shit.” And he says, “oh, yeah, I don't believe in it. But a friend of mine told me that it works even if you don't believe in it.” That feels analogous to the way that I flow through the history of painting. I'm not an art historian, I'm never gonna know everything about this, but if I'm attracted to it, I know that I can pick it up and I can take it apart and I can use it, and I don't necessarily need to know why I make the connections I make. I just have to trust it.

Maybe this is a relevant thing to bring back up, about how spending more than a day on a painting would feel embarrassing. At this point, I can spend months on a painting. Sometimes I delve deep into painting techniques to learn how to build something. It's taken over as something that is interesting to me. This is something I do every day, I might as well get good at it. When I have this kind of erotic attraction to an idea or an image, I go through this process of playing with it, and pulling it apart, and finding places that I still feel confused by. Even in photo shoots with my partners, we'll throw out ideas to see what produces the weirdest or most compelling images. At that point, I still have more than a month ahead of me sitting with that image. So if it starts to die on the vine, if it doesn't have that question mark still lingering in it, this openness in it that I can still enter into and feel confused by – that's the thing that keeps them interesting to me, keeps them open.

I have a friend, Amanda, who lives in rural Pennsylvania. She takes these really beautiful photographs of herself, and she's one of the only people who I see consistently producing images that I feel both very attracted to and very confused by in a way that feels generative for me. We've developed a relationship where I'll make a painting a year based on a photo that she's taken. Otherwise I shoot everything, I do all the editing, and collecting of the objects and materials. It's really become this full on theater productions, in addition to all the painting.

![]()

![]()

Mary Maria (Amanda), 2024

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

![]()

![]()

Mary Maria (Amanda), 2024

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

Mary Maria (Amanda), 2024

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

You can really see the point where you started creating these images. They became about the body in relationship to objects, or the body's relationship to objecthood. They are a little bit abject, but not quite all the way there. The feet that are cut off, but they're not cut off, they just exist as just a foot in the frame. I was also thinking about the painting you have of the boy's face with painted hands and all the sticky hands [Hands and Prayers, 2022]. It feels like it's poking its nose into the territory of “this is a hand, but it's not.”

There was an earlier one where my friend Virginia and I organized this photo shoot in her ceramic studio, and I think we were there for three hours. I didn't know exactly what I wanted. I wanted three people all throwing a vessel at the same time, all these hands kind of interrupting each other and making the process more difficult. In the end, we did get a photo out of it, but it took forever, and that was down to not really knowing what I was looking for. But during a brief interlude we took to eat some food, I snapped a photo on my iPhone of Virginia biting into a clementine to open up the rind, and she still had the slip on her hands. It's about painting, but it’s internal to the scene. It's not interjecting painting into the environment, it's finding painting in the environment.

So the colored latex painted hands very much came out of Virginia (2022), as a way of inserting painting into the environment.

That's also the painting that I have gotten the most pushback on. Just using a kid's face was freaky. While making the image, if anything, he (Henry, age 11) was bored; but showing that painting, there's a real sensitivity to consent and images of children. It was also not that long after the Balenciaga thing with Michaël Borremans, the images with the teddy bears. It was really interesting to see how that “PizzaGate,” pedo discourse had permeated people's brains.

So the colored latex painted hands very much came out of Virginia (2022), as a way of inserting painting into the environment.

That's also the painting that I have gotten the most pushback on. Just using a kid's face was freaky. While making the image, if anything, he (Henry, age 11) was bored; but showing that painting, there's a real sensitivity to consent and images of children. It was also not that long after the Balenciaga thing with Michaël Borremans, the images with the teddy bears. It was really interesting to see how that “PizzaGate,” pedo discourse had permeated people's brains.

![]()

![]()

Hands and Prayers, 2022

oil and dye sublimation on linen, 52 x 43 inches

Hands and Prayers, 2022

oil and dye sublimation on linen, 52 x 43 inches

And even more recently that Sally Mann show in Texas getting censored.

That's been a long-time problem for her since the 90s.

This isn’t new pushback, maybe just within the current political and cultural climate. Perhaps with this change in administration, it's starting to rear itself in a similar way again.

For sure, that 90’s cultural-social conservatism is back hard. And what comes with it is these Satanic Panic vibes that are brought back to the forefront. In a way, it's interesting to think about what would have happened to Chris Ofili or Sally Mann or Mapplethorpe, if the Internet had existed.

“It has a politics in it that’s hard to see if you're not in the middle of an explosive political moment. There is a memory that gets newly enlivened when the politics of the moment matches the politics of the time that an object was made. It feels like a battery that's holding on to energy that’s dormant when the politics aren’t right.”

What’s especially troubling is that the Right is more unified in their fear or opposition than the left is in their resistance to that fear, or in defense of art.

It's very true. They really have cohered in a frightening way, and it's an international movement. Sorry to keep riffing on this, but when Occupy [Wall Street] was happening, there was this weird moment where all of a sudden, going to museums, the work felt different. Looking at Dada works from the 1910’s and 20’s, it felt like those works were holding on to something that I hadn’t noticed before. It has a politics in it that’s hard to see if you're not in the middle of an explosive political moment. There is a memory that gets newly enlivened when the politics of the moment matches the politics of the time that an object was made. It feels like a battery that's holding on to energy that’s dormant when the politics aren’t right. It's interesting to imagine going forward, now that we're re-entering this fascist era. The last time the Fascists were in power, there were artists there, there were the Futurists. There was Albert Speer, they had an aesthetic, and they were actually pretty good at it. Conservatives nowadays have no aesthetic. All they can do is say that art is bad.

I'm really curious to see how that changes. Ten years ago there was a lecture with Odd Nerdrum and British Conservative art historian Roger Scruton. It started off normal enough, it was anti-contemporary and pro-kitsch. Within 45 minutes, especially once they got to audience questions, it was really clear just how Euro white-nationalist that aesthetic ideal was. Outright saying contemporary art is a cosmopolitan thing coming in from outside, and we need to retain our European heritage. It's really nasty stuff. I'm still seeing that stuff metastasize in the background of the art world and now that there's that Peter Thiel / Dime’s Square stuff. You wouldn't think that those two worlds would be connected, but they are.

I'm really curious to see how that changes. Ten years ago there was a lecture with Odd Nerdrum and British Conservative art historian Roger Scruton. It started off normal enough, it was anti-contemporary and pro-kitsch. Within 45 minutes, especially once they got to audience questions, it was really clear just how Euro white-nationalist that aesthetic ideal was. Outright saying contemporary art is a cosmopolitan thing coming in from outside, and we need to retain our European heritage. It's really nasty stuff. I'm still seeing that stuff metastasize in the background of the art world and now that there's that Peter Thiel / Dime’s Square stuff. You wouldn't think that those two worlds would be connected, but they are.

Pots and Pants, 2021

oil and dye sublimation on linen, 48 x 33 inches

oil and dye sublimation on linen, 48 x 33 inches

Yeah, and there’s Roger Kimball at the New Criterion who represents that old guard, similar to Scruton. I feel like he's been on this tip for decades now, and it's his time to shine. I do wonder what the left has to counter that, if there’s a cohesive movement on the horizon. You talk about Occupy [Wall Street] a lot, and that was a paradigm moment where there was a semblance of cohesion. It doesn't feel like there's a group anymore, which is scary.

For sure. The feeling that all leftist possibilities are foreclosed is deliberate, I will say, from my perspective, and this is just my two cents, I think that politics has to come first. I don't think that artists are making it. I think that from the 1880s through the 1940s, artists were all very politically aware and politically engaged. But I think that they almost couldn't not be, and those political movements had to be there for them to attach themselves to. You know, the Futurists aren't making fascism. Mussolini is making fascism, and the futurists are there.

It's like that Milton Friedman quote about the best ideas just laying around. You kind of have to be laying around as an artist. We would be having a very different conversation if Bernie [Sanders] had won in 2016. I don't know that it would have cohered a leftist movement, but it would make the politics of the art being made more clear. I'm a Marxist, and I believe there are issues in the foundations of the economy that are being played out. But there's an incoherence in the art world that follows that incoherence in politics. And I think that it's the idea of a second Trump administration, with him going to Chicago day one, that makes me think that there will be an art that will follow it. But they're starting from very little. Their aesthetic is AI – I don't know that there's anything for them to build on yet.

There are clearly people who are trying to figure out how to support a conservative art movement, but all they have is our language. They can’t articulate it outside of the left’s critical language. The things that get promoted are just depoliticized versions of political art from the left, whether it's actively leftist artists, or just people who are casually progressive.

That's a frontier that I'm nervous about, especially making the work that I make, let's be honest. I met up with some friends of mine, when my most recent show was most of the way done. We had some drinks and sat around and we talked about this, and I said, “is there a world where 40 years from now I'm being held up as somebody who's important to a nascent conservative painting movement?” They bring up the abjectness and queerness and a sort of sexual perversity that might make that reading difficult, but I'm not convinced that I'm fully out of the woods on that. It's something that I think about a lot. I'm doing what I'm doing because I think it's relevant, but it makes me nervous that it's relevant for bad reasons. I try to talk the talk and make sure that I'm supporting my friends and being a leftist in my everyday life. But what am I leaving out? I think that I'm doing the right thing by picking up those ideas and trying to pervert them and pull them over into this other discourse. But if we've learned anything in the last 10 years, it's that people's media literacy is underwater and they might just not see it. I have no idea.

It's like that Milton Friedman quote about the best ideas just laying around. You kind of have to be laying around as an artist. We would be having a very different conversation if Bernie [Sanders] had won in 2016. I don't know that it would have cohered a leftist movement, but it would make the politics of the art being made more clear. I'm a Marxist, and I believe there are issues in the foundations of the economy that are being played out. But there's an incoherence in the art world that follows that incoherence in politics. And I think that it's the idea of a second Trump administration, with him going to Chicago day one, that makes me think that there will be an art that will follow it. But they're starting from very little. Their aesthetic is AI – I don't know that there's anything for them to build on yet.

There are clearly people who are trying to figure out how to support a conservative art movement, but all they have is our language. They can’t articulate it outside of the left’s critical language. The things that get promoted are just depoliticized versions of political art from the left, whether it's actively leftist artists, or just people who are casually progressive.

That's a frontier that I'm nervous about, especially making the work that I make, let's be honest. I met up with some friends of mine, when my most recent show was most of the way done. We had some drinks and sat around and we talked about this, and I said, “is there a world where 40 years from now I'm being held up as somebody who's important to a nascent conservative painting movement?” They bring up the abjectness and queerness and a sort of sexual perversity that might make that reading difficult, but I'm not convinced that I'm fully out of the woods on that. It's something that I think about a lot. I'm doing what I'm doing because I think it's relevant, but it makes me nervous that it's relevant for bad reasons. I try to talk the talk and make sure that I'm supporting my friends and being a leftist in my everyday life. But what am I leaving out? I think that I'm doing the right thing by picking up those ideas and trying to pervert them and pull them over into this other discourse. But if we've learned anything in the last 10 years, it's that people's media literacy is underwater and they might just not see it. I have no idea.

Maria as Madeleine, 80 E. 11th St. Apt 403 (Ashley), 2024

oil, PVA, silver leaf, and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

oil, PVA, silver leaf, and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

Soft Reins, First Tools, 2023

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

I hope that's not your problem.

It is something that I have to stay aware of. I do sometimes not make work because I think it doesn't have enough of that other thing in it that might make it a difficult pill to swallow for somebody whose politics I don't like. It certainly does affect my choices.

I think censorship and saying no to art and images is more reactionary than leftist. So by not censoring yourself, I think you're already on the right track.

The Veneration of St. Agatha’s Breasts, 2023

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches

oil and dye sublimation on linen mounted on board, 19 x 15 inches