Originally from Nairobi, Kenya, Tahir Carl Karmali is a multidisciplinary artist working primarily in sculpture, photography, and drawing.

Through these mediums, and more recently through video and sound, Karmali explores the harrowing systems of stratification navigated by migrants, laborers, and artists in order to produce and sustain banal aspects of daily life.

We spoke to the Brooklyn-based artist about the deception of beauty, the business of art, his early career in Nairobi, and his forthcoming work.

![]()

PARADISE VII, 2019,

screen printed acrylic on natural dyed canvas, 60 x 39 inches

You went to school for hospitality and marketing. Could you give us a brief rundown on how you ended up being an artist?

Firstly, I grew up in Nairobi. So the idea of being an artist, as a career path, wasn't anything that was highlighted or even thought of, even in my art classes. While we would be looking at a lot of artists, you know, there was literally one commercial gallery in Kenya, and most of the commercial galleries and other galleries were framing stories that would sell touristy paintings of wildlife and elephants–Kenya kitsch, basically. I really didn't have that much experience, even though I did manage to meet a lot of artists when I was there, and, at the same time, I did actually apply to go to art school. In my final year in high school, in May of 2005, my brother passed away. I ended up applying and getting into hospitality school because I figured, okay, I like cooking, and that's kind of creative, I'm interested in hospitality, and marketing is kind of like graphic design, I guess, right? I mean, this is the train of thought of an 18 year old; it's not like I knew much about how the world works.

I ended up going to university, and still sort of drawing and doing ink paintings and photography, and so on. Art has always been something that I've been doing. I'm actually really happy that I got that degree because it made me go all around the world and do a whole bunch of things and see various aspects of the world and how the world operates beyond just what you would typically see, especially if I were doing a fine art degree. I got to learn econ and business and all of these other sorts of structures of the world. A big moment was when I was working for a tech firm in Nairobi, and I was getting really depressed because it was taking up so much of my time, and I started to learn more about the world after university. I started to go to more museums and be more and more exposed to the world, and realized that I was in the wrong lane and not doing what I really wanted to do. I just moved into a residency, a kind of subsidized artists studio called Kuona Trust, and I have concentrated on my art practice ever since then. I knew that I wanted to come to New York, so I did my master’s degree in photography at SVA.

![]()

My Contingent, 2019

handmade paper and cotton skim, 78 x 23 x 7 inches

What was the first piece of art that you remember creating?

I was always making paintings, sculptures, etc., but because of my interest in photography, when I moved to Kuona Trust in 2012, I got really interested in telling stories and narratives through portraiture. My first solo exhibition, Value, was the very first time that I thought “Okay, I can call this a collection of work.” This body of work hit a lot of nerves. I photographed male sex workers in Nairobi, in black and white, holding their most valued possession. It was exhibited in a gallery in Nairobi, where sex work is illegal, and also being gay is illegal in Kenya. It was a very provocative show, and it was also one of the reasons why I wanted to leave Nairobi as a queer indvidual. It was one of those things where I was speaking about myself as well as the enemy, which is similar to a lot of my work: I'm talking about myself, but I'm also talking about these very extreme versions of people who have a similar reality.

![]()

![]()

Value series

Can you talk a little bit more about the reception of that piece?

Some artists I knew wouldn't even walk into the gallery while that show was on, they wouldn't even want to look at the photographs, because they knew what they were. It caused a lot of commotion amongst the artists community there. It was also something that people would avoid wanting to talk about; there was this active avoidance of it. There was also this treatment towards me that just wasn't pleasant in any way, but it was a way for me to set a boundary with some of these misogynist artists.

How was being in New York affected your art? Do you feel like it's moved away from this direct representation?

Moving to New York was really helpful for me, not only just being exposed to art that I would resonate more with, but especially learning about and seeing art in person, versus just experiencing through reproductions or pictures online and in books. I realized that one of the reasons why I live here in New York City is to be free to express myself and move around and essentially not have to worry about, you know, getting death threats, or having people put you in the newspaper, and all of that.

But I also didn't want to be an artist that goes around being like, “I'm the African artist that's gay, that's making gay African art.” These are important narratives that need to be expressed, but I already made work about this, I've already discussed this, and I live this reality. I think that there's also a lot of power in not wanting to exploit my identities in order to sell art. I wanted to get into art making and an understanding of art on a deeper level.

But I also didn't want to be an artist that goes around being like, “I'm the African artist that's gay, that's making gay African art.” These are important narratives that need to be expressed, but I already made work about this, I've already discussed this, and I live this reality. I think that there's also a lot of power in not wanting to exploit my identities in order to sell art. I wanted to get into art making and an understanding of art on a deeper level.

![]()

PARADISE IX, 2019,

screen printed acrylic on natural dyed canvas, 60 x 39 inches

PARADISE IX, 2019,

screen printed acrylic on natural dyed canvas, 60 x 39 inches

There’s a blurb on your website that says something about your work being social commentary, or these loaded gestures, in the form of beautiful works of art. Do you think that there's always an undercurrent of deception in beauty, or that one should always remain skeptical of beautiful things?

I think that's true enough. Personally, I do think the work that I make is beautiful. I don't actively try to over-aestheticize these objects and materials, because it's easy to make it even more luscious or unctuous, so that the viewer could be more deceived by it. I think that there's a simplicity to how this beautiful aesthetic comes through in the work, which I think is important in terms of the message behind it. I believe that you should be very wary of beautiful things, or things that seem too good to be true, especially as of late, as we learn more about, for example, how recycling is a farce. The reality is that capitalism and marketing is designed to make everything look beautiful around you so that you can spend your money. That’s something that pulls from my experience working in marketing, this understanding of how much deception goes behind it, and how active and purposeful it is.

What do you think are the strengths and weaknesses of using abstraction or more direct representation. For example, your STRATA (2019) series versus Value, and then there’s the in between which PARADISE (2019) occupies.

My history with photography is where that comes from, the usage of the image. The more I look back at Value, the more I'm happy that I did it. It was a very risky thing to do. When I can't necessarily explain the story materially, then I opt for using a photograph, or a way of manipulating photographs. If the topic that I'm talking about isn't easily converted into a specific material or if I can't find a material that echoes the particular economic circumstance, I would opt for a photograph. I don't know how to explain longing and homesickness with a specific material so that’s why there’s images that come in and disappear, and vice versa, in PARADISE, which is about longing for peace. With STRATA, the material is readily available all around us, so I could actually strip out the cobalt from old phones and put this in front of the viewer in a more direct way.

![]()

Stargazer, 2017

raffia and cobalt oxide, 65 x 38 x 99 inches

What’s the significance in the different ways that the pieces in STRATA are oriented and shown?

The ones that are on the wall and square like blankets, are referencing Kuba cloth. When you go to a museum, you always see this specific type of Congolese textile affixed to the wall; I'm referencing the museological display of these particular objects. Then there's Three children stand and lay in the soil (2018), which are small fixed shrouded bodies, which I really wanted to be on the wall, instead of on the ground, so that viewers wouldn’t walk over them or not see them laying there. I wanted something that would be upright and really engage the viewer directly.

The other ones in the center of the room definitely reference strata itself, these layers of rock or material just existing. Finally, for the ones that are on the dowels, I was trying to figure out how I wanted to display this material, these raw things, and make it beautiful. When I was rendering the sculptures, after the material had been dyed, I was wondering how to rearrange them and fold them and I started looking at the unraveling of the cell phone batteries and of the other materials I was using.

The other ones in the center of the room definitely reference strata itself, these layers of rock or material just existing. Finally, for the ones that are on the dowels, I was trying to figure out how I wanted to display this material, these raw things, and make it beautiful. When I was rendering the sculptures, after the material had been dyed, I was wondering how to rearrange them and fold them and I started looking at the unraveling of the cell phone batteries and of the other materials I was using.

![]()

Three children stand and lay in the soil, 2018,

raffia, cobalt oxide, copper, graphite, lithium, 101 x 76 x 9 inches

In 2018, you were on a panel discussion about decentralizing the art world and blockchain. What was your position then and has it changed since?

My position, which hasn't changed, unfortunately, is that the whole idea around NFT's is how much money we can make off of it. Anything that's been written about NFT's, anything that is constructed around NFT's, is all about how to make money. At least that's everything that I've read, or heard people and artists talk about surrounding it – it’s just not interesting to me.

I get that blockchain technology is really important for artists to have a ledger for artworks, and I have a phobia of selling artwork in a strange way, because I feel that I would not be able to track where they're going or if they’re going to be resold, etc. I think that it's a really elegant solution to actually have some kind of ledger for the sales for artists. But, when you have these crypto punks, or when it starts to become about Logan Paul or Pokemon, these things that sold for so much, it becomes all about how much money is being made. That's just not interesting for me – it's not art anymore. I'm not getting that visceral reaction that I want when I see an artwork, I want to see artworks that impact me; just because something sold for $15 billion doesn't necessarily impact me in any way.

I get that blockchain technology is really important for artists to have a ledger for artworks, and I have a phobia of selling artwork in a strange way, because I feel that I would not be able to track where they're going or if they’re going to be resold, etc. I think that it's a really elegant solution to actually have some kind of ledger for the sales for artists. But, when you have these crypto punks, or when it starts to become about Logan Paul or Pokemon, these things that sold for so much, it becomes all about how much money is being made. That's just not interesting for me – it's not art anymore. I'm not getting that visceral reaction that I want when I see an artwork, I want to see artworks that impact me; just because something sold for $15 billion doesn't necessarily impact me in any way.

![]()

Untitled (shadows and entropy), 2020 -2021,

Conté and pencil on cotton paper, 38 x 50 inches

There’s an interview with Beeple in which he says “I would never call myself an artist. That's so pretentious.”

Let me be pretentious.

Was that 2019?

That was early 2020, about a year ago.

I think Elevator seems to touch upon the difference between content and art. I don't think it's explicitly mentioned, but the whole startup-pitch flavor of the video is similar to the current insatiable thirst for content.

I think that is one of the reasons why I left Instagram. In a way, what was starting to happen for me – and I can't speak to the same realities of other people making art – is that I felt myself becoming beholden to Instagram. I was starting to pay attention to the way that the public engages with the artwork, that you have to post at this time of the day, or this needs to happen in the post. All of these things were a hindrance to me thinking about what I want to make, how I want to push things, or how I want to create. It felt that my work was more about creating content to fill a specific space, because that's how I'd achieve relevance. Instead of thinking about my own art practice–what the artwork was, what the artwork was supposed to fulfill–I started to evaporate through these platforms.

I think a lot of artists operate very differently. For some people it's really helpful, and it works really, really well for them. I’m touching on subjects like child labor, suicide, etc. and all of these things are harsh topics. It started to get really ridiculous that the measurement of engagement started to become more important than the artwork itself. When I started to realize this, I got really scared for my own practice, and I needed to disengage from Instagram. I don't want to aestheticize trauma just so that I can get likes on Instagram.

I think a lot of artists operate very differently. For some people it's really helpful, and it works really, really well for them. I’m touching on subjects like child labor, suicide, etc. and all of these things are harsh topics. It started to get really ridiculous that the measurement of engagement started to become more important than the artwork itself. When I started to realize this, I got really scared for my own practice, and I needed to disengage from Instagram. I don't want to aestheticize trauma just so that I can get likes on Instagram.

![]()

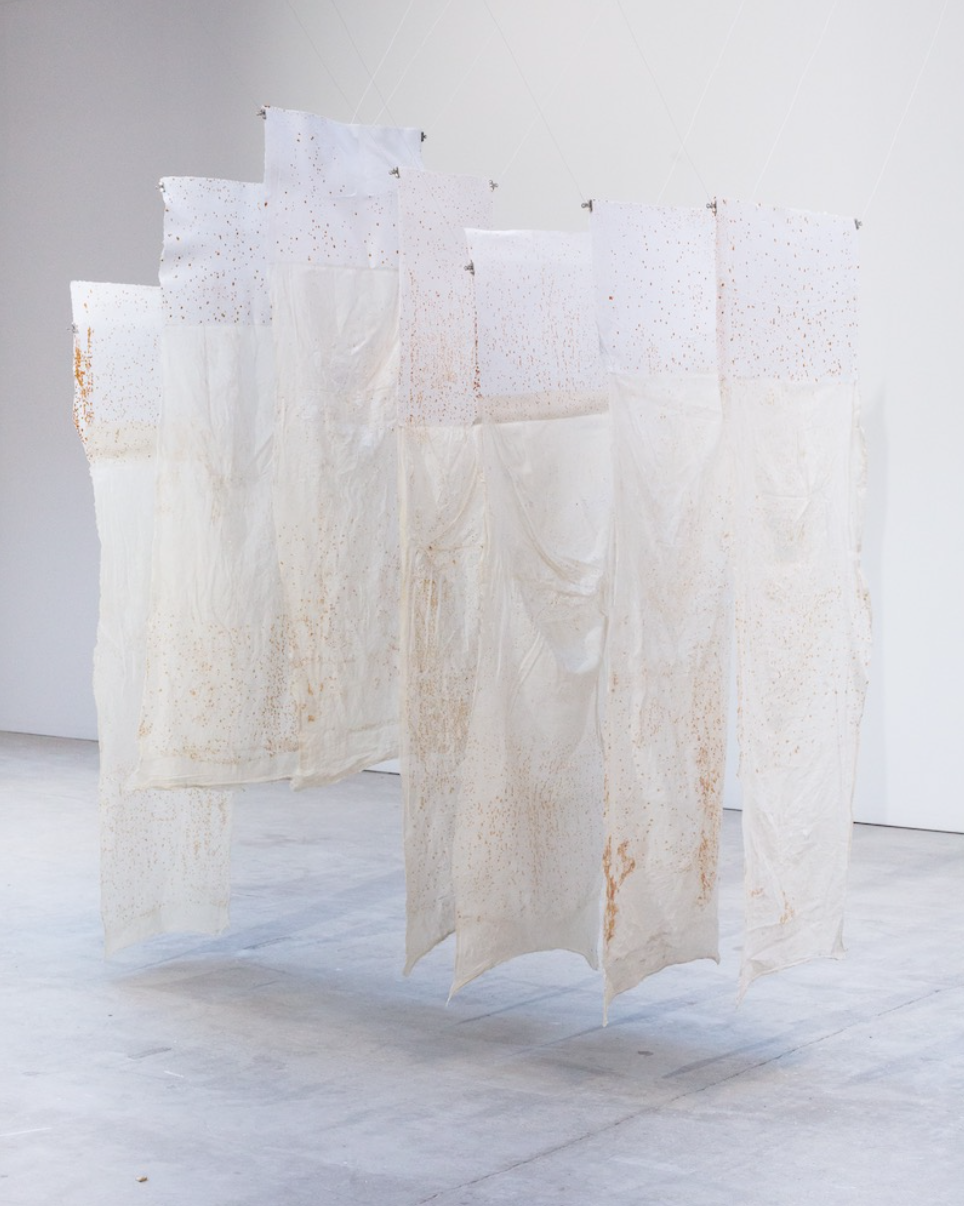

PAPERwork installation, IPCNY, 2019,

102 sheets of handmade paper pulped from photocopied government-issued identification documentsand commercial paper; with aluminum mesh, photocopy collage, rust transfer, and other mixed media

collage, dimensions variable

PAPERwork installation, IPCNY, 2019,

102 sheets of handmade paper pulped from photocopied government-issued identification documentsand commercial paper; with aluminum mesh, photocopy collage, rust transfer, and other mixed media

collage, dimensions variable

It’s a big move for an artist to choose not to have more visibility. Has it helped so far?

Personally, yes. It's helped my practice. I am now less conscious about how well the work might photograph or how it can be experienced on a computer or a cell phone. That's one of the things about my work: if you experience it on your cell phone, especially the STRATA series and Lotus (2019), the irony of it is there, but when you see it in person, you actually get the visceral feeling of the work. Firstly, the scale is completely different on a phone. Secondly, the texture and materiality of it is also very different. Also just mental health wise, not having to worry about all that has been great. I'm drawing more and I’m more engaged with thinking about work in an active way.

I do miss it sometimes because I don’t get to see my friends as much and you also get isolated in a way where people just don't inform you about stuff, because it's also a messaging platform.

I do miss it sometimes because I don’t get to see my friends as much and you also get isolated in a way where people just don't inform you about stuff, because it's also a messaging platform.

![]()

LOTUS, 2019,

steel, aluminum, Personelle netting, and aircraft cable, 14 x 14 x 10 feet

LOTUS, 2019,

steel, aluminum, Personelle netting, and aircraft cable, 14 x 14 x 10 feet

So what are you getting at with Elevator?

It is written by Mia Rovegno, Elizabeth Thys, and myself. The idea essentially came from pitch culture and this idea where we would make a cacophony of pitches. We started getting into it and reading a lot of actual pitches for new technology. If you look at where money is being invested, especially in tech, it’s incredibly dystopian. There are companies that have millions of dollars invested into them in order to create, I don’t know, artificial venison, and other absurd things.

Mia was on the subway and wrote all of this jargon and started to put it together into a sort of poem. She came to my studio, and we immediately recorded the first version of it. We would pull language from Apple tech pitches, break down full sentences, and reorganize the words. While it does sound, in part, like nonsense to most people, it makes sense in a metaphoric way more than in a literal way. It's actually a really fun script to annotate and see how the rhyming structures work, because it's very much written like a poem; a very, very long poem that, in real time, watching it being performed, is really hard to annotate.

Mia was on the subway and wrote all of this jargon and started to put it together into a sort of poem. She came to my studio, and we immediately recorded the first version of it. We would pull language from Apple tech pitches, break down full sentences, and reorganize the words. While it does sound, in part, like nonsense to most people, it makes sense in a metaphoric way more than in a literal way. It's actually a really fun script to annotate and see how the rhyming structures work, because it's very much written like a poem; a very, very long poem that, in real time, watching it being performed, is really hard to annotate.

![]()

Still from ELEVATOR, a work in progress by ThoughtThought (Mia Rovegno, Elizabeth Thys, and Tahir Carl Karmali)

As an artist, we're constantly pitching for things; as tech people, we're constantly pushing for things. The more we started doing research, the more dystopian our future started to look. How much of ourselves are we letting go to these companies? Elevator comes together as an arc on how we have experienced researching this particular industry. It's very similar to what we do as artists, and for a lot of other industries too. I went to an opening just recently (it's been a long time since I've been around people), directors of galleries and people who work in arts administration would say things like “So tell me what kind of artists are you? Is your work figurative? Is it about your identity?” And I was like, I haven't engaged with somebody about talking about my art practice in this elevator pitch format in such a long time. It seemed ridiculous that I would have to be able to boil down my entire practice as an artist to five or six sentences. I wasn't ready to engage with this again. It's very similar to the tech world right? Where every opportunity is an opportunity to sell your work, to sell your product, to sell what or who you are. It's shocking.

It seeps into everything; it's business, really. As a professor, I can't in good conscience let my students leave my classroom unless they know both aspects of this, both aspects of what it means to be an artist: to have to build your own practice, and to come up with ideas and do this active thinking about making work, or designing, investigating, researching and to prepare them for what most of the world just wants to hear; I do teach my students how to pitch. I also make them write essays and critically engage with these corporate ideas around design.

It seeps into everything; it's business, really. As a professor, I can't in good conscience let my students leave my classroom unless they know both aspects of this, both aspects of what it means to be an artist: to have to build your own practice, and to come up with ideas and do this active thinking about making work, or designing, investigating, researching and to prepare them for what most of the world just wants to hear; I do teach my students how to pitch. I also make them write essays and critically engage with these corporate ideas around design.

![]()

![]()

Still from ELEVATOR, a work in progress by ThoughtThought (Mia Rovegno, Elizabeth Thys, and Tahir Carl Karmali)

Still from ELEVATOR, a work in progress by ThoughtThought (Mia Rovegno, Elizabeth Thys, and Tahir Carl Karmali)

So what do you have coming up? What are you working on now?

I read this white paper, about who builds your architecture. It goes through how a lot of these major architectural and engineering features are actually built: What are the living conditions of all of these construction workers? How do they go through this entire thing? I reached out to my lawyer, and I started doing a lot of research around how we get arugula or cilantro; just the state of American farming and what the reality is for a lot of American migrant laborers. COVID made this whole experience incredibly extreme.

This project is very much to do with that, but also at the same time, it's to do with entropy and death. You know, very light topics of entropy and death. I read the Robert Smithson essay about entropy last year, and with being in New York City and seeing the mass graves, you can't help but feel like there is this sort of looming dark cloud of the end of the world.

This project is very much to do with that, but also at the same time, it's to do with entropy and death. You know, very light topics of entropy and death. I read the Robert Smithson essay about entropy last year, and with being in New York City and seeing the mass graves, you can't help but feel like there is this sort of looming dark cloud of the end of the world.

![]()

Untitled (shadows and entropy) , 2020-21,

Conté and pencil on cotton paper, 22 x 30 inches

This project is very much to do with that, but also at the same time, it's to do with entropy and death. You know, very light topics of entropy and death. I read the Robert Smithson essay about entropy last year, and with being in New York City and seeing the mass graves, you can't help but feel like there is this sort of looming dark cloud of the end of the world.

![]()

Left to right:

A landscape between hard surfaces; A tracing along a diagonal ridge;

A

curve cut from the grid, 2020,

screenprint ink on cotton paper, 22 x 30 inches each

Left to right:

A landscape between hard surfaces; A tracing along a diagonal ridge;

A curve cut from the grid, 2020,

screenprint ink on cotton paper, 22 x 30 inches each

Visit Tahir Carl Karmali’s artist page.

Watch the trailer for ThoughtThought’s trailer for Elevator here.