Baseera Khan

We talked to Baseera Khan about psychic space, material, and the coupling of rage and softness. Through their performance and other visual mediums, Khan often exposes the universality of certain experiences as deserving of a critical double take. Khan was recently awarded the Brooklyn Museum’s UOVO award for which they will receive a solo show at the Brooklyn Museum, debuting Fall 2021.

Khan lives and works in New York City.

Do you have any specific aesthetic experiences that influence your practice now?

Khan lives and works in New York City.

Do you have any specific aesthetic experiences that influence your practice now?

I remember when I was five or six, up until my early teenage years, I would do overnight projects with my mom and we would sew all of our clothing. During the holidays, as Muslims, you’re supposed to wear new outfits, and this was before you could really get a traditional outfit at the store. My mother was such an amazing seamstress and designer in India that when she came to the states she would just make everyone’s clothes. It was kind of a local, underground business. I would stay up picking fabrics, and end up sleeping next to bulks of fabrics when, I imagine, most kids my age were sleeping next to teddy bears. This is something that actually inspired the Karaoke Spiritual Center of Love project at the Sculpture Center in 2018 which was part of the In Practice that they do every year. They have a catalog online so it's accessible.

Installation view, Snake Skin, 2019,

Simone Subal Gallery, New York, NY

Any early critical experiences that inform your work now?

I’m gonna stick with the childhood stuff. When you’re something like six or seven years old and into your early teens, so much changes, and though we think that it’s all so long ago and that it doesn’t stick with us, I constantly think that I’m seven years old when I’m making my artwork. One of the things that I remember most is that we would all get into a car and drive to Dallas, Texas. I grew up in Denton, Texas, and we would have to go on these day trips because my parents were undocumented. We were always going to this massive warehouse space that was an administrative building with all of these people waiting to get called in order to build paperwork. Even though that must have been hard as a child, I actually loved those trips. My parents never let me eat fast-food or ice cream, things like that, but during these trips I was allowed to get popsicles and McDonalds and all of the stuff I wasn’t allowed to have normally. I was always like yes, the American dream: McDonalds and popsicles.

I’m bothering to say that, because when I was older I shoved the idea of immigrant family precarity into the back of my mind. It wasn’t until grad school that I started looking at Youtube videos of what the climate of the Reagan years were like. I found videos of police officers chasing people at the border in Texas trying to detain and deport them. Basically, it looked just like it does now, we see the same thing today as we did when I was a kid in the ‘80s.

I’m a late bloomer, so I went to grad school in 2010-2012 at Cornell, and it wasn’t until then that I started unpacking the ways in which I had so much joy in this really precarious situation. And, if we’re unpacking the Karaoke Spiritual Center of Love, there’s a little bit of oil and water, which is also in a lot of my work. I'm really interested in making work that feels like the kitchen sink. But it's a very distinct way of cooking, where it feels like there's a lot of ingredients, but there really isn't. There’s a lot of joy, mystery, and a lot of fun but then there’s this really deep, dark aspect which coincides with that. I think maybe that’s why people like my work, and it’s what makes my work interesting to me. I should unpack that more! Having a distinct experience, and the world around you never matching up is what I’m interested in.

I’m bothering to say that, because when I was older I shoved the idea of immigrant family precarity into the back of my mind. It wasn’t until grad school that I started looking at Youtube videos of what the climate of the Reagan years were like. I found videos of police officers chasing people at the border in Texas trying to detain and deport them. Basically, it looked just like it does now, we see the same thing today as we did when I was a kid in the ‘80s.

I’m a late bloomer, so I went to grad school in 2010-2012 at Cornell, and it wasn’t until then that I started unpacking the ways in which I had so much joy in this really precarious situation. And, if we’re unpacking the Karaoke Spiritual Center of Love, there’s a little bit of oil and water, which is also in a lot of my work. I'm really interested in making work that feels like the kitchen sink. But it's a very distinct way of cooking, where it feels like there's a lot of ingredients, but there really isn't. There’s a lot of joy, mystery, and a lot of fun but then there’s this really deep, dark aspect which coincides with that. I think maybe that’s why people like my work, and it’s what makes my work interesting to me. I should unpack that more! Having a distinct experience, and the world around you never matching up is what I’m interested in.

So it has a lot to do with memory and the past?

Well, you’re asking me to recall memories of aesthetic and critical moments, so I’m thinking right now of these moments. I actually think that memory is a fallacy, I don’t rely on memory to make the work. Though it is a situation of the mind, because a lot of the ideas that I pull from come out of being present somewhere and then, all of a sudden, having this feeling of “wait… one million people also have this experience on a daily basis; I have to do something with this.” An example of that is Privacy Control (2019), which is a work that involves long mirror panels where you can see through the glass if the light hits it correctly. I transcribed the last chapters of the Quran behind it on vinyl text with my queer female voice, in this age of constant fatwa and Charlie Hebdo. It does a couple of things: it shields me from heteronormativity, patriarchy, and male violence; it invokes questions of who is safe and what is safety, and what exactly are those things for? But, it also does this other thing, which is that it acts as a massive selfie stand. When the piece is lit correctly at a certain type of day, it just looks like one huge mirror. People pass by and fix their hair and do cute selfie poses. There’s a transition in my work there, where it’s nothing but joy, and then there’s another moment where it’s very heavy.

![]() Privacy Control, 2019,

Privacy Control, 2019,

two-way mirror, steel pipes, vinyl text, 16 x 8 feet

Can you tell us more about the performance aspect of it?

In that particular performance of Privacy Control, it's held up with scaffolding. So some of them are like 20 feet tall. I'll put on a hiking light, and climb the scaffolding. So I'll be trapped between the wall text and the artifice of the two way mirror, and wherever I shine the light, people in the audience can read the text. And then they just see this person climbing higher and higher and higher.

While you do literal collages, I see that formal and conceptual language in your other work. Where does that come from?

You’re picking up on something very instrumental to my practice. I don’t make body-art, I don’t make identity politics art. I am very much about presence, and I think about the materials which are seen by a billion people all at the same time in this one second. It’s a psychic space that I’m interested in. For example, I was sitting in a mosque that my family had helped build in Texas, looking through the paned glass. The women sit on one side of the mosque, and the men sit on the opposite side, and the men can’t see us but we can see them. All of a sudden I see my reflection, I see what’s behind me, and through the mirror. It was a mindfuck! There are 1.6 billion Muslims in the world alone. If you cut that in half, that’s like 800 million practicing Muslim women who see exactly what I’m seeing. For me, that’s not about identity politics, it’s about everyone across the board, from Chinese, Nigerian, Swiss, to American Muslims. It’s a very George Battaille situation: How this one material is on a funny crime show, it’s also the material used in a mosque, a Jewish synagogue, fancy buildings in New York city, at every gym, and above your bathroom sink. So, I get into it and create hopefully successful works (laughing). Making new work is the worst because there’s a week where you think you're the best artist in the world, and then the next you’re totally embarrassed and want to die!

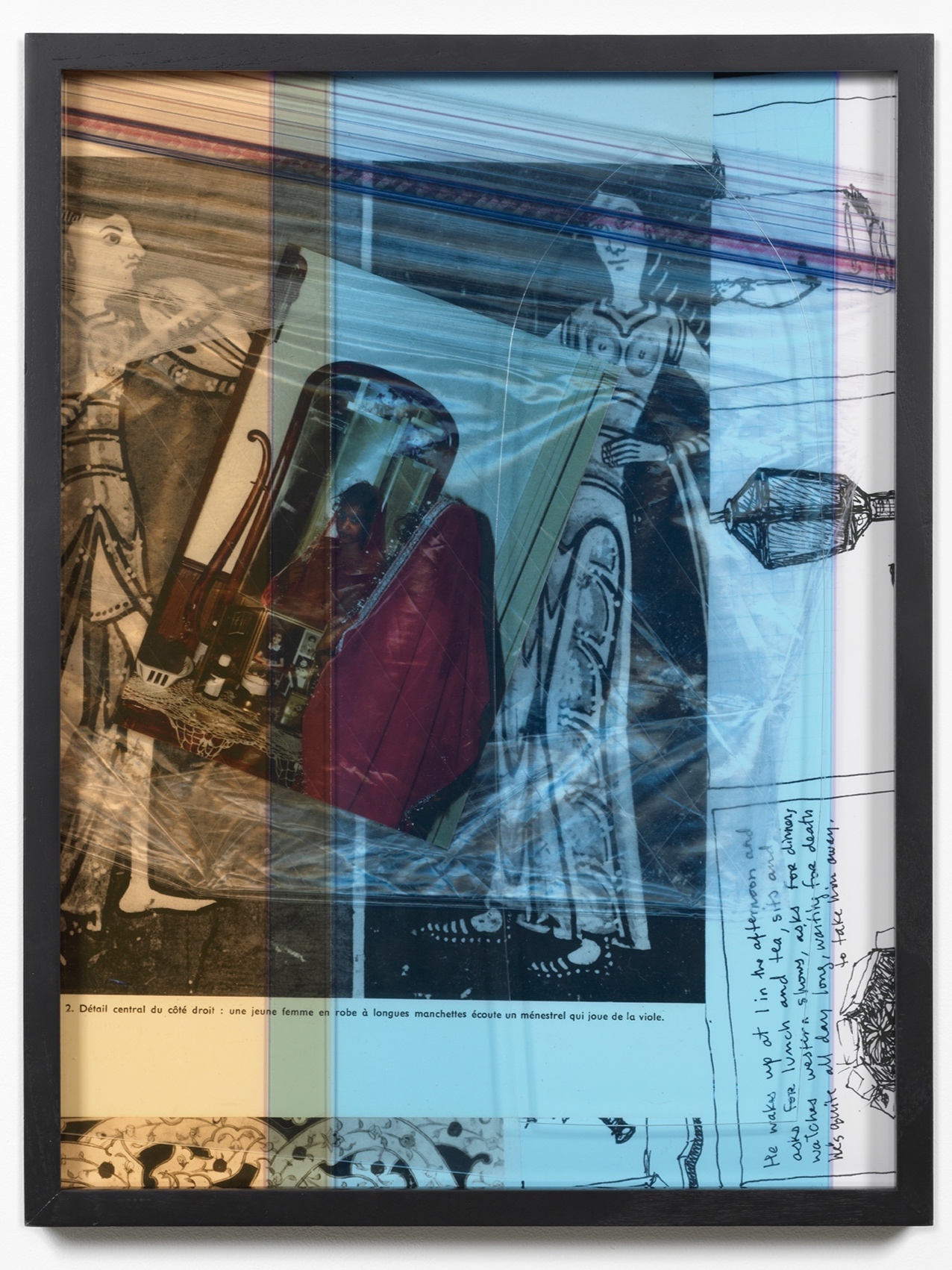

Reflection, 2019,

chromogenic print, cardboard, acrylic, 30 x 24 inches

I’m working on a TV series [By Faith] with a six week residency program at the Kitchen, where guests come into this weird green space and we just hangout and do weird shit together. Last night, I did one with Amy Sillman, whom I met when I was 20, while getting my undergraduate degree at the University of North Texas and she was doing a solo project at the University. When I graduated college, it was at the moment when the internet was becoming normalized but it wasn’t necessarily a thing that everyone had or was expected to use as a primary resource. Amy and I were both thinking about all of these younger artists that are in school, who may be working towards these new genres of art which are completely mind-fuckingly interesting. But, in terms of tradition and composition and really understanding the history and legacies of painting, sculpture, or performance in these very distinct, art historical ways, I may have been the last class for that type of education. Education changed completely with the internet. And, yes, it’s going to change again because of the pandemic. I was a total art-nerd girl, I know how to do classical technique–drawing, painting, sculpture–and I just got really into the specificities of the ways these art historical works came about. Then, I started questioning “what is art with a capital ‘A’?” And I got into a situation where I stopped making work and said, “I’m not making art anymore, fuck the art world” and I left the art world for a good ten years. I had been working and making art the whole time, I just didn't engage with the legacies of art history, or have shows and stay in touch with people, go to residencies. I was just like, “Fuck that.” When I came back, I came back pretty severely. The iamuslima show at Participant, Inc was really my first show in New York, and I’ve been running ever since.

Although it may feel more democratized, how do you feel about art being seen increasingly online now, given that your practice has involved so much performance work in the past?

There’s that fascinating “Art History 101” Walter Benjamin essay, “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” which was written so long ago, but there’s this beautiful moment where he was talking about nodes, networking, how the oratic space is deconstructed and how the masses have access to art. There’s people much smarter than the three of us making those connections with social media. So now we have this pandemic, we have millions of people dying, because their bodies are compromised. Nobody is going to school, Americans aren’t going places that they have always been able to go. In April, I was walking by the Brooklyn Museum and just started crying. That is the one place where I always felt that I belonged. You can enter alone, people don’t typically come up to you, you can spend the day just looking at art, reading books, and nobody bothers you (in most cases). Not having access to physically seeing art got to me in a major way. It’s especially interesting to see what new forms are coming from this time. There’s something fascinating about Tik Tok, and how it became a political tool. And a lot of the mini dramas and comedies are fucking good.

But honestly, there’s always been a threat that painting is “no more.” In the ‘90’s, everyone was talking about how painting has become out of fashion. The brushstroke was gone! But, really, it’s in this moment that perhaps painting will disappear, because you physically are not usually able to go into the space to see a painting. Of course painting isn’t dead, but things are really going to change. I don’t think that people will be going into art school. Our daddies lost their jobs! The middle class relies on their parents, and they were the ones sending us to school.

Right now I’m playing with the medium of TV. And I’m not the only experimental artist who’s made weird shit for TV. There’s Pee Wee’s Playhouse, The Shape of Things with Julio Torres, etc. When you think about the way in which Dutch painters in the 16th and 17th century started to paint still-lifes, it was the first Instagram moment. Of course, the patronage system evolved from that, which eventually led to the early gallery system. Now we have Art Basel online! That’s why I was pointing to Tik Tok, because it brings us back to the traditions of sponsorship. Brands will find people on Tik Tok and say “Hey, you look really good, let’s put some shoes on you and make some money.” That is increasingly what artists are expected to do. I don’t know about you, but I do not feel cool. I feel like I’m always struggling for people to see me as an artist, and even I was given a pair of Margielas because I was willing to get on their Instagram story and show that I was wearing their shoes. It’s so obvious that they needed a smart brown Muslim girl to show herself in Margiela so that rich Muslims allover the world will buy their products, but that’s what’s happening to the art world.

Right now I’m playing with the medium of TV. And I’m not the only experimental artist who’s made weird shit for TV. There’s Pee Wee’s Playhouse, The Shape of Things with Julio Torres, etc. When you think about the way in which Dutch painters in the 16th and 17th century started to paint still-lifes, it was the first Instagram moment. Of course, the patronage system evolved from that, which eventually led to the early gallery system. Now we have Art Basel online! That’s why I was pointing to Tik Tok, because it brings us back to the traditions of sponsorship. Brands will find people on Tik Tok and say “Hey, you look really good, let’s put some shoes on you and make some money.” That is increasingly what artists are expected to do. I don’t know about you, but I do not feel cool. I feel like I’m always struggling for people to see me as an artist, and even I was given a pair of Margielas because I was willing to get on their Instagram story and show that I was wearing their shoes. It’s so obvious that they needed a smart brown Muslim girl to show herself in Margiela so that rich Muslims allover the world will buy their products, but that’s what’s happening to the art world.

Seat #10, 2018,

pleather, artist's underwear, prayer rugs, synthetic hair, 52 x 54 x 3 inches

You’ve used your sound-blanket work in a few different iterations. Can you talk about the continual activation of that work?

I made that specifically for the iamuslima show. The first time that the acoustic blanket came into my life was when I was working at a rock club in Denton, Texas. I would record bands in my house, and I learned that the bathroom is like a soundbooth because of the way it's fortified. We would get under acoustic blankets in the bathroom and try to get these crystal clear sounds. At some point, I cut a whole in the blanket to get some air, and to run cords and mics out of it. When I was working on iamuslima, I was thinking about all of those things. There was a bit of tongue-in-cheek that I was pushing in terms of the expectation that I knew the audience would have. Wearing a big dumb black acoustic blanket doesn’t necessarily look like a hijab, does it? If I’m nude underneath it, if I’m inviting people under and playing music or doing comedy routines, it’s pretty hard to pinpoint that girl.

Then, history happened. The night before Trump was inaugurated, people started contacting me and asking to borrow these acoustic blankets for protests because Trump had hired private police to throw percussion bombs at the demonstrators in order to break them up. These weren’t lethal, but they would shake you up. I started doing protest performance work where I would go out and hold the hands of people who were demonstrating. Then, in December 2018, I was canonized (laughs). It’s the most nonsense art that I’ve made, and it’s the thing that the Guggenheim bought. I guess I’m the glitch in the system.

I do enjoy obfuscating my body. The screens that you see on the backside of the work I'm doing now with the Kitchen, I created them in the same way I did with the acoustic blankets. After the show's over, I'm taking them down and covering myself with them. And I'm going to do similar performances under it with light instead of cutting a hole out.

I do enjoy obfuscating my body. The screens that you see on the backside of the work I'm doing now with the Kitchen, I created them in the same way I did with the acoustic blankets. After the show's over, I'm taking them down and covering myself with them. And I'm going to do similar performances under it with light instead of cutting a hole out.

Acoustic Sound Blanket, Number Six, 2019,

Felt, silk, cotton, gold custom thread embroidering, cut out, 90 x 85 inches

How does the marriage of softness and rage manifest in your work?

I am enraged, sometimes, when I make work. Instead of just being suspended in that space, I tend to get really creative and mentally active, which leads me to lucid dreams, and then to making my artwork. I often wake up and fall back asleep throughout the night, and that’s how I’m able to remember my dreams. It’s a bit of a gift and a curse, but dreams are very important to me. There’s a respect, both in my personal life and in my relationships, to traditions of Islam, this country, art and art history, but I am very willing to be mischievous and fuck with it. Simply because it’s untrue, all of it is untrue. I have a sacrilege and sanctimonious relationship to many traditions. I’m currently working on a film of Braidrage (2017), and in that you’ll see a lot of me beating the wall with chains and there’s charcoal everywhere, and also beautiful moments of caressing and massaging. That’s living! To live in America alone is to know that we’re standing on blood. We have to reconcile with that in some way.

I think that that's what makes being American just so unique to other places. Anytime I've traveled to other countries, they always ask me, “Why are you guys so politically correct? Why are you guys so obsessed with identity politics in America?” And I think that it's so funny to step out of the country and learn how people see us in other countries, whether it's the West or the East. And so I think that has a lot to do with the unique history of the Transatlantic slave trade, you have a very unique history to the Caribbean islands, and the fact that America is country that asserts itself as exceptional. Now we have this moment where we are singular in history, because we're doing the best at killing people during the pandemic.

I think that that's what makes being American just so unique to other places. Anytime I've traveled to other countries, they always ask me, “Why are you guys so politically correct? Why are you guys so obsessed with identity politics in America?” And I think that it's so funny to step out of the country and learn how people see us in other countries, whether it's the West or the East. And so I think that has a lot to do with the unique history of the Transatlantic slave trade, you have a very unique history to the Caribbean islands, and the fact that America is country that asserts itself as exceptional. Now we have this moment where we are singular in history, because we're doing the best at killing people during the pandemic.

99 Holds, 2017,

Indoor rock-climbing wall made from 99 unique poured dyed resin casts of the corners of the artist's body embedded with wearable Cuban chains, hair, and hypothermia blankets, 120 × 297 in

To refer back to Braidrage, I was hoping you could talk about your use of hypothermia blankets.

I was thinking about Braidrage in terms of a collective sense of self. It wasn't necessarily my body, I was thinking of all of those who had been displaced. The body parts are usually made up of silver wearable chains and hyperthermia blankets, because those are the materials that large countries like China or Russia or America excavate for. Which is why you still have poverty, because without poverty, you can't control the masses, the whole Hegelian thing. You always need to oppress someone in order to remain on top. And unfortunately, a lot of these materials are the reason why.

And for anybody identifying as a woman, the chains, and the rings are symbols of ownership, not sovereignty, which was an important thing for me to embed as well.

And for anybody identifying as a woman, the chains, and the rings are symbols of ownership, not sovereignty, which was an important thing for me to embed as well.

Privacy Control, 2019,

Privacy Control, 2019,