Sarah Slappey

Sarah Slappey’s bodily compositions act as stimuli for the sense of touch. While the subjects may be void of a clear personhood, the slippery, dancerly limbs that twist in and out of the picture frame often allow for viewers to enter that space.

We spoke with Slappey about her earliest artwork, horror films, the wonders of touch, and the double edged sword of femininity.

Sarah Slappey lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Do you have a rose and thorn for the past week?

We spoke with Slappey about her earliest artwork, horror films, the wonders of touch, and the double edged sword of femininity.

Sarah Slappey lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

Do you have a rose and thorn for the past week?

My rose is being back in New York. I did a Chelsea gallery walk around, which I haven't done that in so long. There's some amazing shows up right now. I have friends who have shows up, and getting to celebrate them and their work was wonderful.

I went to my friend Inka’s [Essenhigh] opening at Miles McEnery and the work was fantastic as always. Gina Beavers is great, and Kyle Dunn. Kyle and I show in the same gallery in Zurich, so we've known each other for a while. His color palette is so brilliant. And I thought Jacolby Satterwhite at Mitchell-Innes & Nash was good and surprising.

My thorn is trying to walk into a few galleries, and people with clipboards who were like, “excuse me, do you have an appointment?” One of them I just abandoned when I saw someone asking for appointments. At Sikkema Jenkins I was the only person in line for the Louis Fratino show, which is so good. I didn’t have an appointment but they were like “Oh, it doesn't matter, just come on in,” which was great. But that was a point of frustration.

I went to my friend Inka’s [Essenhigh] opening at Miles McEnery and the work was fantastic as always. Gina Beavers is great, and Kyle Dunn. Kyle and I show in the same gallery in Zurich, so we've known each other for a while. His color palette is so brilliant. And I thought Jacolby Satterwhite at Mitchell-Innes & Nash was good and surprising.

My thorn is trying to walk into a few galleries, and people with clipboards who were like, “excuse me, do you have an appointment?” One of them I just abandoned when I saw someone asking for appointments. At Sikkema Jenkins I was the only person in line for the Louis Fratino show, which is so good. I didn’t have an appointment but they were like “Oh, it doesn't matter, just come on in,” which was great. But that was a point of frustration.

![]()

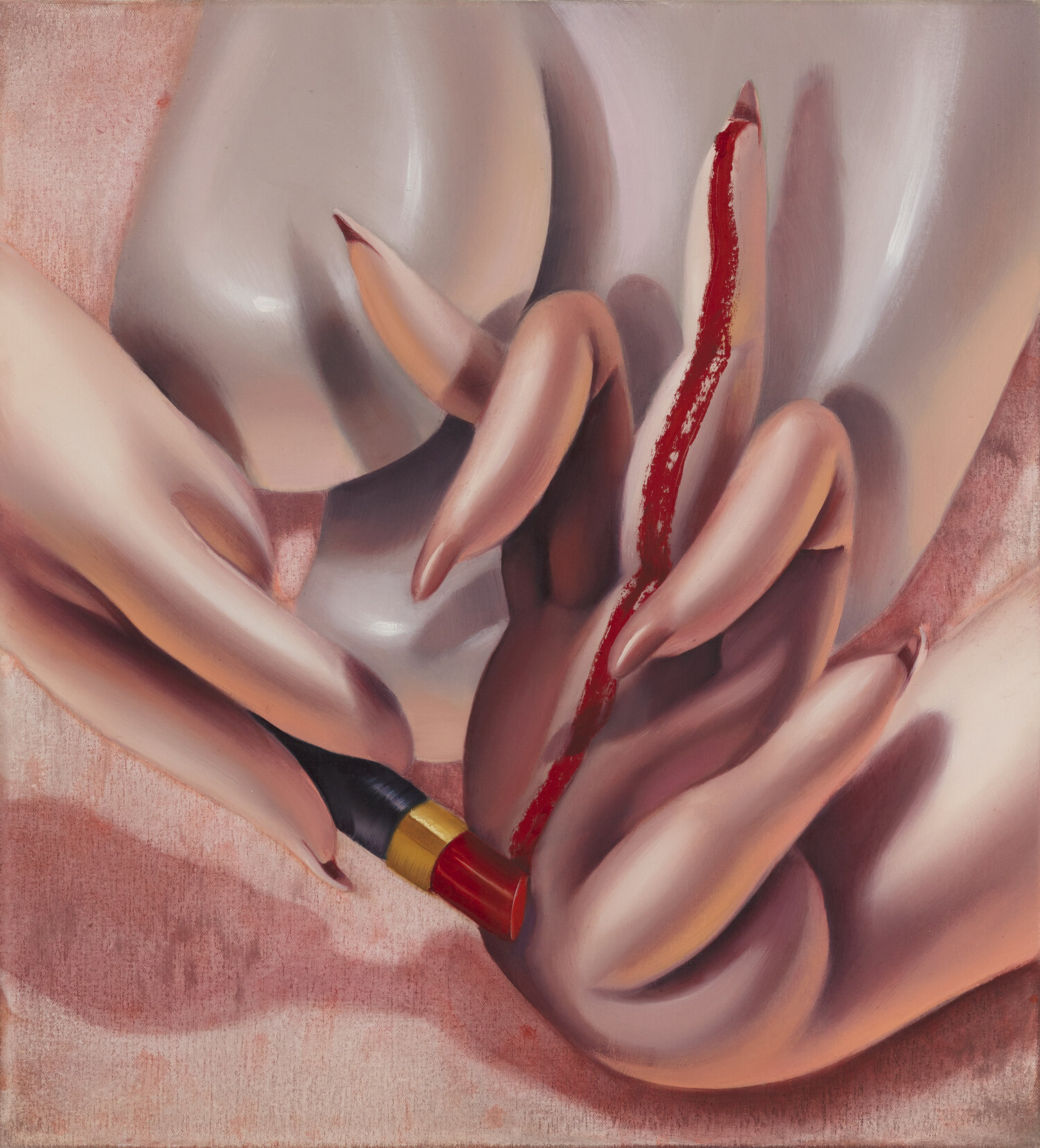

Lipstick, 2020,

oil on canvas, 22 x 20 inches

What kind of art did you make as a kid?

No one has asked me that before. As a kid, I always drew people–always, always, always–I never felt connected to representational art that did not have the human figure in it. When I was really little I would wake up on Saturday mornings, and there was a show called Style with Elsa Klensch. Elsa Klensch was this woman with an Australian accent who would go to all of these fashion shows and report on the couture designs. It came on every Saturday morning, and I would sit there, ready with my sketchbook to draw the people walking down the runway. And so I thought, maybe I wanted to be a fashion designer, but I didn't care about clothes. I just needed a reference point to draw the human figure. I was always drawing or painting. I didn't have much of an interest in sculpture, although, as a kid, everyone goes through that phase of making ceramic ashtrays for their parents who don't necessarily smoke.

I still have the ash trays. I don’t smoke, but that would be a fantastic show, now that I think about it. Ashtrays that artists made as kids. It would be a deep research project, you'd have to find that stuff.

And then going through high school and college, I always worked from the human figure, mostly the female body. Even looking back at my undergrad work now, I was making these portraits of invented nude women. They were always beautiful, but they were always hurting themselves in these strange, surreal ways. I had no idea why I was making this work. This is my freshman year of college, so when we had to write a few paragraphs on the meaning behind our work, I thought I was so clever because I wrote that the meaning is nothing. In hindsight, I'm looking at this arc thinking, “Sarah, this is what you're doing now.” It was all there.

I still have the ash trays. I don’t smoke, but that would be a fantastic show, now that I think about it. Ashtrays that artists made as kids. It would be a deep research project, you'd have to find that stuff.

And then going through high school and college, I always worked from the human figure, mostly the female body. Even looking back at my undergrad work now, I was making these portraits of invented nude women. They were always beautiful, but they were always hurting themselves in these strange, surreal ways. I had no idea why I was making this work. This is my freshman year of college, so when we had to write a few paragraphs on the meaning behind our work, I thought I was so clever because I wrote that the meaning is nothing. In hindsight, I'm looking at this arc thinking, “Sarah, this is what you're doing now.” It was all there.

![]()

Pink Ribbon, 2020,

oil on canvas, 55 x 49 inches

Your drawings of the fashion models must be so cute.

I do have all of my sketchbooks. They were all the same, with the blue-lined paper and every single cover had to be hot pink–every single one. I love looking at them when I go home.

I noticed you had a sculpture on your Instagram of these fingers. I know you already said you didn’t do much sculpture growing up, but are you interested in pursuing that? Your paintings feel so haptic, because there's all these layers interacting in a very three-dimensional way.

I think you're exactly right. When I'm painting them, I'm not imagining a two-dimensional surface. I'm imagining a three-dimensional figure. I made that ring sculpture for a particular show, and I haven't gone back to it. I think there is something there. I’m on the edge of finding ways to transform this work into three dimensional work, but I haven't taken that step, because I’m not sure I know how. It hasn't commanded itself quite yet. Maybe it will take the right amount of boredom in the studio or I’ll get tired of making so many paintings.

Do you find yourself pushing your process in a certain direction, or do you let it take you along for the ride? And how important is finding the correct pace for your process?

When I was in grad school, I was in this running pace. I would try something, and if it didn't work, I'd throw it out the window. Then I’d try something else that didn't work, and I would throw that out the window because we were doing critiques all the time. I think I was in this people-pleasing moment. In the studio, I'm not a runner, I put one foot in front of the other. A few paintings down the road, you're 10 steps ahead. I found the pace that works for me. The difference between one painting and another might be relatively small, but then one painting and another within the same show–that difference might be a little bit larger.

I do my best work in a certain comfort zone where I'm pushing, pushing, pushing a little bit, but not throwing stuff out of the window. That makes your job unnecessarily hard, like walking through a dark room with pieces of furniture and running into every piece of furniture before I found myself on the other side. Why torture yourself?

I do my best work in a certain comfort zone where I'm pushing, pushing, pushing a little bit, but not throwing stuff out of the window. That makes your job unnecessarily hard, like walking through a dark room with pieces of furniture and running into every piece of furniture before I found myself on the other side. Why torture yourself?

![]()

Reach, 2018,

oil on canvas, 32 x 30 inches

What's your relationship to writing and criticism about your work?

I saw a few pieces of writing recently, because I just opened this show. If you're lucky you get gifted with pieces of writing that help explain the work to you. Which is amazing, because there are times I hear interpretation of my work that I think “oh no, this is not right, I must be way off the mark with what I'm showing to people.” The interpretations that I got from this past show were so amazing. I felt like they gave me nuggets of wisdom that I can then pull from. They take it forward for me, I can reference their writing when I'm making decisions in the studio. I should write these people “Thank you” notes. I think the interpretations I've gotten specifically from female writers have been the most on the nose. It feels like having the world of women talking about their bodies together.

Is there an element of storytelling behind any of them, especially the ones where they're crawling through the forest? Is there a story about what they're doing or who they are?

I think the narrative is less about who that person is, because I want it to feel like an extension of the viewer’s body, and about the place. Especially in that work, with all the nature, the narrative was about what place this could possibly be or what it feels like to be in these surroundings. I love horror movies and the cinematography of horror movies, if they’re good it can be fucking mind blowing. I think I was somewhat consciously and unconsciously filtering that into these paintings, trying to recreate an emotional narrative or a tenor. Something where you can feel a spotlight in the middle of the forest, or even a narrative or a sound, like the rustling sound, that is its own little moment of a story, without giving you too much.

![]()

Yellow Touch, 2018,

oil on canvas, 44 x 42 inches

I'm wondering about the materials that make their way into your paintings. There was a lot of foliage in your earlier works, and now it seems as if you're moving towards these materials that are wet and smoky. What’s the emotional tone of that transition?

I don't know if I can explain, even for myself, why that exactly happened. It happened towards the end of a particular body of work. From a technical point of view, I probably just made too many of these forests and needed a break, I needed to step out of it and see what happens outside of this scene. And I realized that I could zoom in on the body even more. It wasn't just a hand, it was the whole body really squished up against the picture plane, and when that happens, you don't need the background, you don't need that sense of place. I think it can be a distraction. I hate backgrounds, I will always hate backgrounds. I find them to be visual junk. I liked that foresty place, because that gave some additional narrative, but I don't know how much of that I need–when does that spill over into extraneous information? I'm really just interested in the body, and when you put so much of the body into the picture plane, having a place of respite with the background as a nothing-space works really well.

![]()

Pearl Drop, 2020,

oil on canvas, 48 x 44 inches

What does touch mean for you? How important is that ability, with hands or otherwise, to your work?

Obviously, the paintings are visual, but I want them to be more about touch than anything else. Because maybe aside from smell, touch is the most visceral thing that we do. It's so loaded. You touch your partner, you touch your own body, but then people also get into fist fights. It's this way of communicating that has a wide range of emotional tone to it. Sometimes you can't read it. The wide meaning is what is very interesting to me, and also gives a wide interpretation of the work.

As a person, as a woman, sometimes you feel very sexy and like you want to be touched. And other times you feel like a disgusting animal, like “get away from me.” Of all the senses, touch is the most important thing, and maybe the second is visual, but I don't know how to make a painting that does not have the visual component.

As a person, as a woman, sometimes you feel very sexy and like you want to be touched. And other times you feel like a disgusting animal, like “get away from me.” Of all the senses, touch is the most important thing, and maybe the second is visual, but I don't know how to make a painting that does not have the visual component.

![]()

Lavender Lattice, 2020,

oil on canvas, 64 x 58 inches

Even in horror films, if someone's touched by a ghost or something, you can feel it, your body reacts.

You get cold chills, it’s like your body touches itself. If you react to something with cold chills, your body is giving itself a touch sensation, but without any external stimulus. How is that not the most interesting thing?

Most of your older works depict a solitary figure. I noticed that recently you’ve been painting scenes that depict interaction between bodies. What kind of relationship do these characters have to each other?

There are two reasons. One, I added more people in from a technical, studio standpoint. And two, it happened from a conceptual reason that more people needed to come in after taking out the natural elements. I'm not interested in portraits, or person-hood, necessarily. I'm interested in the body, putting my viewer in a body or a space where they feel like they are the body in the picture plane. Because of that, if it's a lot of interacting figures, you understand the sense, but if it's one person then it feels like you’re looking at this other person who has a name, an identity, and it's not me. From the technical aspect of it, after taking out the background and zooming in on the body, there's only so much you can do with one figure before it gets to be a little monotonous. During the drawing process, I realized adding more figures made sense in terms of organization of the picture plane.

![]()

Tied Up II, 2020,

oil on canvas, 64 x 58 inches

By erasing the subject you're allowing the viewer to place themselves in the painting?

Yeah, which I think is the only way to get towards touch, because if it's another person, you can't feel it. If you're looking at a very traditional portrait of someone, you don’t feel like “I'm wearing this beautiful taffeta dress,” or “I am participating in this crucifixion.” It's always over there, not here. If you chop off a head and put limbs coming in from every which way, to me, it makes me feel like I'm a part of this moment, this bodily experience.

That makes sense. You don't see your own face when you look down, all you see are your limbs.

Even if I painted my own face in these paintings, I don’t think I would feel attached to them. I would feel like I was painting somebody else.

How did you arrive at where you are now in your visual language?

I want to say that it was all a continuation, putting one foot in front of the other, especially once I could slow down a little bit. After I finished school in 2016, I was in my own studio, and could work at my own pace. When I first started to arrive at this body of work, which is now conceptually pretty formed, I wasn’t reinventing the wheel every time. That happened in about 2017. I was applying to this flat file program by Tiger Strikes Asteroid, an artist run gallery in Brooklyn. Every year they do a show where you submit a work on paper, I wanted to do it, I had nothing going on, and I needed a deadline. I had been working on a really large scale, and I was like, “okay, now I have to do something small.”

When I travel and go to museums, I have for many, many years sketched the hands in paintings that I like. When you're standing in front of a da Vinci painting that you might never see again, it's a really special moment. I have this sketchbook full of hands that I drew, and I thought, “Oh! just do some hand painting for this flat file program.” After I did it, I thought it could be something. I just kept doing them more and more and more–that's sort of the start of when things made sense.

When I travel and go to museums, I have for many, many years sketched the hands in paintings that I like. When you're standing in front of a da Vinci painting that you might never see again, it's a really special moment. I have this sketchbook full of hands that I drew, and I thought, “Oh! just do some hand painting for this flat file program.” After I did it, I thought it could be something. I just kept doing them more and more and more–that's sort of the start of when things made sense.

![]()

Drop, 2018,

oil on canvas, 40 x 36 inches

Did you like your grad school experience at Hunter?

The biggest thing that I got from the experience is the community, because I was already living in New York for a long time. I wanted to stay in New York, and so it just made sense to go to school here, where I could make all these great friends. I think it would just be really hard to come to New York after an MFA and not have roots already here. The studios are great, and I think it's very student driven, which is a strength, and the art history Professors are excellent.

We touched on why you leave the faces out a bit. Does it have to do with a sense of anonymity or shielding them–so that they still get to hold this presence without revealing too much?

Yeah, that's a very good point that I had never considered before, but it is very poetic to think that these women get to be whoever they want to be, and are shielded from exposure, in control. But their genitals are exposed, so It’s a double edged sword because it's empowering that they are anonymous, but anonymity can also remove someone's personhood. I always like a double edged sword.

I don't want to touch it, but I do. It's sensual, but it's also a little bit revolting.

It's because I'm confused. I feel both things simultaneously and I don't want to figure it out. I don't want to have a firm answer, because then why would I do it anymore? I don't think that you can arrive at one valid feeling about your body in the world and just be at peace with it, especially as a woman.

Have your figures always been so fluid and elastic? The way that they move and the way that they’re layered is like tying a knot.

I guess it took me a little while to find that. I think that was how I wanted to paint from the beginning, but I fought it because it felt too seductively easy to me. I still feel like I'm taking the easy way out, making it’s very blended and luscious. I've heard Marilyn Minter say “do what's easy because what's easy for you in the studio is not necessarily what's easy for everybody else.” I had to find my way out of the noise in order to do it and really take pleasure in it. I grew up with a very gender-normative family in the south where femininity is sort of seen as this prize–like a competitive sport–where women should be soft and graceful. That is all in my work. I also grew up doing ballet, and I was still taking ballet as an adult when I moved here. You can see that in small ways in the paintings, how the thumbs are usually tucked in a little bit. There's like a lot of movement in it that I think has come from layers and layers of personal history. That became this elastic aesthetic.

![]()

Pink Touch, 2020,

oil on canvas, 28 x 25 inches

Tell us about those luscious smears of lipstick that made their way into the work featured in in your solo show, Powerplay, at Sargent’s Daughters.

I wanted to do something with lipstick because of what I was just saying about where I’m from and competitive femininity. That's a part of my makeup, and as a painter, I saw these oil sticks, the way they go onto canvas, I thought it was like squishing a tube of lipstick, which I’ve always wanted to do. I've always wanted to take a lipstick and bite it off or something!

I was making the work with hands, and I wanted to do something with this lipstick concept, both conceptually and physically. I was thinking about drawing it on your body or your finger. It's very visceral, it looks like a wound or something, it's got this aggression to it. And, on the subject of narratives, I was thinking about the way we mark up our bodies with plastic surgery markings or when you're an adolescent and the first one to fall asleep at a sleepover gets drawn on, different ways of marking our bodies that signify power. Lipstick was perfect, and I haven't often put objects in my paintings, well maybe I’ll put pearls and chains in a painting, but I want to be careful that I don't throw random stuff in there without having a really strong reason to do it.

I was making the work with hands, and I wanted to do something with this lipstick concept, both conceptually and physically. I was thinking about drawing it on your body or your finger. It's very visceral, it looks like a wound or something, it's got this aggression to it. And, on the subject of narratives, I was thinking about the way we mark up our bodies with plastic surgery markings or when you're an adolescent and the first one to fall asleep at a sleepover gets drawn on, different ways of marking our bodies that signify power. Lipstick was perfect, and I haven't often put objects in my paintings, well maybe I’ll put pearls and chains in a painting, but I want to be careful that I don't throw random stuff in there without having a really strong reason to do it.

![]()

Lipstick Landscape, 2020,

oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches

This reminds me of that killer essay by Melissa Hyde called “The ‘Makeup’ of the Marquise: Boucher's Portrait of Pompadour at Her Toilette.” She specifically talks about the social implications of makeup and artifice in the Boucher portrait.

The idea of painting makeup is akin to when you put two mirrors up against each other, it’s this infinite regression. Is it paint? Is it makeup? Is it makeup? Is it paint? It's funny that you say that, because I have these raw powdered pigments, and I was thinking, “what else is there because paint is makeup and makeup is paint.” I've been figuring out how to dust it onto painting so that it looks like you've “made up” different parts of your body. We'll see how well that works both physically, and archivally.

There’s that double edged sword again. One side is liberation.

I think it's liberating in that I get to explore my love/hate relationship with femininity. There's a lot of currents happening. One is about the body and touch and things that are both beautiful and gross at the same time. Another part of it is trying to figure out how I feel about womanhood and the hyper femininity that I grew up with. I can do whatever the fuck I want, I can love it and then hate myself for loving it, but that exists in tandem with talking about the female body in this world, which is a very complex body to live in. I think being in the studio, thinking about this stuff, and getting to talk about it is liberating, even though it's confusing. You look back, and you think, well, I like this feminine thing–but do I like it for the right reasons? Am I doing this for me? Am I doing it for someone else? I don't really know. It feels good but part of you is always questioning why it feels good. Such a back and forth.

The best I can do is just feel confused. That's where I’ve landed, and at least I'm acknowledging it. It's always nice to come to a place where there isn't an answer, if I had the answer, it would be pretty boring. Getting to play around with it all is what’s interesting. I think I come from a place where femininity and masculinity is “figured out” for us. The “answer” of femininity, had I grown up here in New York, would have been a completely different pathway than what it looked like in South Carolina. The answer is different for different people. I really do struggle with it.

The best I can do is just feel confused. That's where I’ve landed, and at least I'm acknowledging it. It's always nice to come to a place where there isn't an answer, if I had the answer, it would be pretty boring. Getting to play around with it all is what’s interesting. I think I come from a place where femininity and masculinity is “figured out” for us. The “answer” of femininity, had I grown up here in New York, would have been a completely different pathway than what it looked like in South Carolina. The answer is different for different people. I really do struggle with it.

![]()

Cloud Tangle, 2020,

oil on canvas, 64 x 58 inches

Friends and Friends of Friends:

Artistic Communities in the Age of Social Media

Schlossmuseum Linz, Austria

Sep 30, 2020 – Jan 6, 2021

Visit Sarah Slappey’s artist page.

︎: @sslappey